Our Announcements

Sorry, but you are looking for something that isn't here.

Zero Dark Thirty is writing our collective history for us — engraving it on the American psyche. The graphic images of who we are and the deeds we have done are intended to inspire confidence and to soothe qualms — now and in the future. We are a Resourceful people. We are a Righteous people. We are a Resolute people who do not shrink from the necessary however hard it may be. We are a Moral people who bravely enter the shadowy precincts where Idealism collides with Realism — and come out enhanced.

In truth we are an Immature people — an immature people who demand the nourishment of myth and legend that exalt us. Actual reality intimidates and unsettles us; virtual reality is the comforting substitute. Zero Dark Thirty is fiction — most of it anyway. Yet critics and commentators have taken as given the story line, the highlight events, and the main character portraits as if the film were a documentary. The one big debate is on the question of whether torture works. The film’s paramount message is that it does, that it did lead inexorably to the killing of Osama bin-Laden, and that anyone who gives precedence to ethical considerations had better be prepared to accept the potentially awful consequences. The heroines and heroes make the right judgment after struggling with their consciences.

That is a dubious conclusion. Moreover, the question itself is wrongly framed. For the intelligence supposedly extracted was of no value in finding bin-Laden ten years later. Even members of the Senate Intelligence Committee have testified to that. Simple logic should lead any thoughtful person to the same conclusion. After all, if so valuable, how is it possible that it took a full decade for the information to lead anywhere — the indefatigable fictional lady notwithstanding (the lady who does not exist in the real world)? The tale as told assumes a static world in which places, persons and politics don’t change. But they do. In ways that the film narrative cannot and does not take account of.

It all comes down to the fabled courier. Without him, the narrative collapses completely. We didn’t have a clue where OBL was between Tora Bora and Abbottabad five years later. His odyssey from one safe house to another in the Tribal Areas, and Northwest Frontier Province (Swat and Bajaur) escaped the CIA with all its ultra-sophisticated high-tech gadgetry. We had next to no human intelligence assets anywhere in the region and did not until the very end. And at the end, it was the Pakistanis who provided us with the critical leads — as acknowledged by President Obama in his announcement of OBL’s killing. That was just a week or so before the White House and the CIA approached Hollywood with promises of cooperation if a film were made that properly hallowed those who brought OBL to “justice” and satisfied the national thirst for vengeance. Both sides kept their side of the bargain.

What of the courier al-Kuwaiti? The official cum Hollywood line is full of inconsistencies, anomalies and logical flaws. A systematic scrutiny of the evidence available makes that abundantly clear to the unbiased mind. That task has been undertaken by the retired Pakistani Brigadier Shaukat Qadir. His account, and interpreted analysis, draws as well on extensive interviews with intelligence and military officials in Islamabad — and with principals in both Northwest Pakistan and across the Durand Line in Afghanistan. This was an independent investigation by a man with an established reputation for integrity. His appraisal and conclusions have been featured in front page stories inThe New York Times, Le Monde and The Guardian yet never widely circulated — or refuted. (Operation Geronimo: the Betrayal and Execution of Osama bin Laden and its Aftermath by Shaukat Qadir (May 1, 2012) — Kindle eBook)

Here is a brief summary of a few key points regarding the official story’s self-contradictory elements.

· According to the CIA, Hassan Gul, was a courier for senior Al-Qaida operatives including OBL and Khalid Sheikh Muhammed (KSM). Gul revealed to the CIA under interrogation the name Al-Kuwaiti, the fact that Al-Kuwaiti was still alive, that he was OBL’s most trusted courier. CIA further stated that it was Gul’s statement that provided detailed insight into his working routines which led (four years later) in 2009 to the feeling that al-Kuwaiti lived in Abbottabad! Assuming all this to be true, it seems a little surprising that it should take them almost four years to move.

· What is even more improbable is that, despite providing such a wealth of information for the CIA, Gul was released as early as 2006 by the CIA into ISI custody. If Gul had provided all the information on Kuwaiti to the CIA and the CIA did not wish to share this information with the ISI, as asserted, how can their releasing him to ISI custody make any kind of sense?

· Is it credible that it took the CIA so long after 2005 to discover Al-Kuwaiti’s identity since Al-Libi, his close collaborator, was also captured by the ISI and handed over to CIA in 2005! Yet, Al-Libi was not questioned regarding Al-Kuwaiti’s real identity — despite Gul’s revelations, despite “enhanced interrogation” techniques? In short, why did it take the CIA from 2004 till 2011 to find “actionable intelligence” to locate and execute OBL?

· Khalid Sheikh Muhammed, captured by the ISI in March 2003, was handed over to CIA soon thereafter. KSM not only knew Al-Kuwaiti by his real name, Ibrahim, according to OBL’s wife, Amal, he had also visited al-Kuwaiti’s house outside Kohat when OBL was resident there in 2002. Yet, he too never was questioned as to Kuwaiti’s identity.

There are two fundamental flaws in the official CIA (and Hollywood) account:

the CIA seems to have been unaware of the intimate relations between Al-Libi and Al-Kuwaiti despite all those Al-Qaida leaders in their custody (most of whom were arrested by ISI) who knew exactly who and where Al-Kuwaiti was — and, therefore, the CIA actually was unaware of the latter’s identity until early 2011; b) still, they insist that the ISI did not provide the lead that ultimately led them to OBL’s hideout, which looks to be equally untrue.

Therefore, the CIA in all probability began tracking OBL only in 2010/11, thanks to the lead provided by ISI.

Let us recall President Obama’s words when he announced that OBL had been killed. Even as he stated that the US acted unilaterally on actionable intelligence, he added, “It is important here to note that our counter terrorism cooperation with Pakistan helped lead us to bin Laden and the compound he was hiding in.”

Against that backdrop, it was logical for the US and Pakistan to launch a joint operation in Abbottabad. Washington decided to reject the idea. Why? Not because we feared a “leak” which made absolutely no sense. But rather because we wanted to make sure that OBL was killed and denied a public legal forum. We also wanted the glory and flourish of a drama with Americans in all the starring roles – we wanted a Hollywood blockbuster.

John Brennan, the White House terrorism chief, gave the game away the next day in offering the world a vivid description of the assault featuring a concocted shootout between the Seals and a pistol wielding Osama bin-Laden who held his wife as a shield while firing off shots. Made for Hollywood indeed.

After a decade of impulsive vengeance, of brutality, of killing, of deceit, of hypocrisy, of blindness and incompetence — we have an encapsulated myth that expiates all that in a drama worthy of our greatness. We have Closure. The American pageant moves forward.

What in fact we have is a rough-spun yarn woven post-hoc to give a semblance of discipline and direction to a fitful, adrenaline driven manhunt that belatedly stumbled upon its objective — only thanks to the critical help of others. Unable to generate any human intelligence, we relied on technology and torture. It didn’t work

The claim that the official U.S. version provides an honest, forthright accounting is unsustainable. The version offered by Zero Dark Thirty substitutes pulp fiction — of the mythological kind — for truth. It satisfies a gnawing hunger; it meets a powerfully felt need. It allows us to avoid coming to terms with how America went off the rails after 9/11. It fosters the adolescent in us.

Thursday, 03 May 2012 09:07By Gareth Porter, Truthout | Report

Posters of 22 fugitives, including Osama bin Laden, line a wall at the FBI headquarters in Washington, October 10, 2001. (Photo: Stephen Crowley / The New York Times)A few days after US Navy Seals killed Osama bin Laden in a raid in Abbottabad, Pakistan, a “senior intelligence official” briefing reporters on the materials seized from bin Laden’s compound said the materials revealed that bin Laden had, “continued to direct even tactical details of the group’s management.” Bin Laden was, “not just a strategic thinker for the group,” said the official. “He was active in operational planning and in driving tactical decisions.” The official called the bin Laden compound, “an active command and control center.”

Posters of 22 fugitives, including Osama bin Laden, line a wall at the FBI headquarters in Washington, October 10, 2001. (Photo: Stephen Crowley / The New York Times)A few days after US Navy Seals killed Osama bin Laden in a raid in Abbottabad, Pakistan, a “senior intelligence official” briefing reporters on the materials seized from bin Laden’s compound said the materials revealed that bin Laden had, “continued to direct even tactical details of the group’s management.” Bin Laden was, “not just a strategic thinker for the group,” said the official. “He was active in operational planning and in driving tactical decisions.” The official called the bin Laden compound, “an active command and control center.”

The senior intelligence official triumphantly called the discovery of bin Laden’s hideout, “the greatest intelligence success perhaps of a generation,” and administration officials could not resist leaking to reporters that a key element in that success was that the CIA interrogators had gotten the name of bin Laden’s trusted courier from al-Qaeda detainees at Guantanamo. CIA Director Leon Panetta was quite willing to leave the implicationthat some of the information had been obtained from detainees by “enhanced interrogation techniques.”

Such was the official line at the time. But none of it was true. It is now clear that CIA officials were blatantly misrepresenting both bin Laden’s role in al-Qaeda when he was killed and how the agency came to focus on his compound in Abbottabad, Pakistan.

In fact, during his six years in Abbottabad, bin Laden was not the functioning head of al-Qaeda at all, but an isolated figurehead who had become irrelevant to the actual operations of the organization. The real story, told here for the first time, is that bin Laden was in the compound in Abbottabad because he had been forced into exile by the al-Qaeda leadership.

The CIA’s claim that it found bin Laden on its own is equally false. In fact, the intensive focus on the compound in Abbottabad was the result of crucial intelligence provided by the Pakistani intelligence agency, the Directorate for Inter-Services Intelligence (ISI).

Truthout has been able to reconstruct the real story of bin Laden’s exile in Abbottabad, as well as how the CIA found him, thanks in large part to information gathered last year from Pakistani tribal and ISI sources by retired Pakistani Brig. Gen. Shaukat Qadir. But that information was confirmed, in essence, in remarks after the bin Laden raid by the same senior intelligence official cited above – remarks that have been ignored until now.

What the Bin Laden Documents Reveal

The initial claims about what the documents from the Abbottabad compound showed about bin Laden’s role in al-Qaeda were not based on any substantive evidence because the documents had not even been read, much less analyzed by the CIA. That process would take six weeks of intensive work by the analysts, cyber-experts and translators, as the Associated Press reported June 8, 2011. But with roughly 95 percent of the work done, the picture that emerged from the documents was starkly different from what the press had been told when the country was riveted to the story.

Osama bin Laden had indeed come up with plenty of ideas about attacking US and Western targets, but officials now acknowledged to Associated Press that there was, “no evidence in the files that any of the ideas bin Laden proposed led to a specific action that was later carried out.”

A month after the analysis of the bin Laden documents was completed, one official told CNN that they showed bin Laden writing about attacks on aircraft carrying Obama and Petraeus in Afghanistan. Another official familiar with the documents told the network, however, that they reflected bin Laden, “in his brainstorming mode.” One official described a document in which bin Laden expressed interest in having a team plan attacks on the United States on the tenth anniversary of the 9/11 attacks. But, an official commenting on the entire collection of bin Laden documents told CNN, “[T]hese were ideas, not fully or even partially planned plots.”

Eight months later, in March 2012, Washington Post columnist David Ignatius, whose writing invariably reflects what top national security officials want to see in the news media, was given a “small sample” of the documents by a “senior administration official.” The two documents he chose to highlight – bin Laden’s musings on shooting down aircraft with Obama or Petraeus on board and attacks on the tenth anniversary of 9/11 – had already been reported by CNN in July 2011. Acknowledging that al-Qaeda did not even have the military technology to shoot down a US plane, Ignatius observed that bin Laden, “still dreamed of pulling off another spectacular terror attack against the United States.”

So, several months after the Abbottabad documents had been thoroughly analyzed and the results digested by senior administration officials, the administration was unable to cite a single piece of evidence that bin Laden had given orders for – or was even involved in discussing – a real, concrete plan for an al-Qaeda action, much less one that had actually been carried out. Far from depicting bin Laden as the day-to-day decisionmaker or even “master strategist” of al-Qaeda, the documents showed a man dreaming of glorious exploits that were unconnected with reality.

“Nobody Listened to His Rantings Anymore”

The reality reflected in the documents from the Abbottabad compound is that bin Laden had been exiled by the leadership of al-Qaeda because he had come to be seen as a loose cannon who was a danger to the organization. The train of events that led to bin Laden’s holing up in the compound in Abbottabad began in August 2003, in a small village in Afghanistan’s Nangarhar province, near the fabled caves of Tora Bora where he led a battle against US Special Forces in December 2001. It was there that the leadership of al-Qaeda conducted a series of extraordinary meetings on its most pressing problem: how to ease bin Laden out of his leadership role in the organization.

Those deliberations can now be revealed because Qadir, the retired 30-year veteran of the Pakistani Army, had served for years in South Waziristan alongside Mehsud tribesmen, with whom he had stayed in contact over the years. After the bin Laden raid, Qadir went back to his former comrades, and they introduced him to three of their relatives who had been couriers for Mehsud tribal militant leader Baitullah Mehsud in his contacts with al-Qaeda’s second-in-command, Ayman al-Zawahiri, during the 2003 meetings.

Mehsud would become the head of the al-Qaeda affiliate organization Tehrik-e-Taliban Pakistan (TTP) in 2007. But in 2009, Mehsud was killed in a drone strike and the organization was splintering over various issues. All three former couriers broke their ties with Hakimullah Mehsud, Baitullah Mehsud’s successor as head of TTP. The political split in the Mehsud tribal community, followed by the killing of bin Laden, released the former couriers from their oaths of secrecy. In early August 2011, Qadir was able to meet separately with each of the three former Mehsud couriers in three different villages in South Waziristan, on the understanding that their names would not be revealed.

After bin Laden moved from the Tora Bora region of Afghanistan to South Waziristan in northwest Pakistan, his health continued to decline, according to the three former Mehsud couriers. Just what ailments were causing the deterioration was not clear, but he was no longer able to walk, and had to be moved by horseback from one house in South Waziristan to another for security reasons.

But an even greater concern of the al-Qaeda shura (or council), according to the former couriers, was what appeared to bin Laden’s colleagues to be his obsession with the idea that al-Qaeda should attack and capture Pakistan’s nuclear reactor at Kahuta. Zawahiri, the second-ranking al-Qaeda leader, who had the task of meeting personally with bin Laden, along with the rest of the shura tried to tell bin Laden that Kahuta was impenetrable. They pointed to the presence of a regular infantry battalion, air defense, guard dogs, mines and a laser security system guarding the facility. And anyway, as they pointed out to bin Laden, there were no nuclear weapons stored there.

But none of that seemed to matter to bin Laden, who seemed delusional on the issue. “Nobody listened to his rantings anymore,” said one of the couriers in a conversation with Qadir. “He had become a physical liability and was going mad,” another told Qadir a couple of days earlier. “He had become an object of ridicule,” said the second courier, recalling that some of the militants in South Waziristan had become aware of his harangues on the subject and were starting to make jokes at bin Laden’s expense. “You can’t have a leader whose people ridicule him,” he said.

Zawahiri had been running the day-to-day affairs of al-Qaeda, but bin Laden was still insisting on participating in major decisions. That situation led Zawahiri to propose during a series of meetings in August 2003 that bin Laden be forced to retire from active involvement in the organization’s decisions. The other members of the shura supported him, according to all three former Mehsud tribal couriers.

The only question was how to get bin Laden to agree. The shura believed bin Laden would only listen to one man: Abu Ayoub Al Iraqi, who had accompanied bin Laden to Peshawar in the early 1980s and had been a mentor to bin Laden when he founded al-Qaeda, then faded into the background. The problem was, according to the ex-couriers, that only bin Laden knew how to contact him. So, the shura decided to present a plan to bin Laden for the capture of the Kahuta nuclear base on condition that it would be subject to the approval of Iraqi.

Bin Laden agreed with the proposal and a courier was dispatched to Iraqi. But unknown to bin Laden, the courier also carried a letter from Zawahiri detailing bin Laden’s condition and requesting Iraqi’s help in convincing him to retire voluntarily for his own safety. The courier returned from visiting Iraqi in September 2003 with cosmetic modifications of the plan, and with the advice that the shura had requested: bin Laden should be housed in a secure location from which he could issue orders, but Zawahiri should continue to act on bin Laden’s behalf in the day-to-day affairs of the organization.

The plan was to let bin Laden believe that he would still be the leader of al-Qaeda from his new safe haven. In reality, the al-Qaeda leaders were sending him into an urban exile to get him off their backs.

The shura considered various options for permanent housing for bin Laden before deciding that he should live a secluded family life in a city that would not be too far from Pakistan’s tribal areas, according to the Mehsud tribal sources. The third-ranking member of the hierarchy, Mustafa al-Uzayti, a Libyan better known by his alias Abu Faraj al Libi, was tasked with finding the best location for bin Laden and his family to reside, according to Qadir’s Mehsud tribal sources.

Al Libi’s first choice was Mardan, about 30 miles from Peshawar, but bin Laden’s courier, who used the alias Sheikh Abu Ahmed al-Kuwaiti, suggested that it was too dangerous because some pro-al-Qaeda individuals were constantly under surveillance by Pakistani and US intelligence agencies. He suggested Abbottabad instead.

After bin Laden approved the construction of a house within a larger compound in Abbottabad, it was Kuwaiti who purchased the land and oversaw the construction. Investigators from Pakistan’s ISI later learned that Kuwaiti and his younger brother moved in with their own wives, along with bin Laden and his large family of two wives, six children and four grandchildren in May or June 2005.

How Did the CIA Find Bin Laden?

Immediately after the Special Operations forces raids that killed bin Laden, a senior administration official who had an obvious interest in peddling a particular narrative about CIA interrogation techniques told reporters that the CIA interrogation of al-Qaeda detainees held at Guantanamo had been a critical factor in finally tracking down bin Laden. According to one version, Khalid Sheikh Mohammed, also known as “KSM,” the mastermind of the 9/11 attack, had identified bin Laden’s trusted courier in 2007; in another version, unidentified detainees had given interrogators the courier’s real name.

The story of bin Laden’s courier was an open invitation for past and present CIA officials who had gone along with the use of torture in interrogating suspects to justify their position. CIA Director Panetta channeled their viewpoint in an interview with NBC, suggesting that, for some of the information that led the agency to bin Laden, interrogators, “used their enhanced interrogation techniques against some of the detainees.” He added, “Whether we would have gotten the same information through other approaches I think is always going to be an open question.” Reutersreported that the story of how the administration learned about the identity of bin Laden’s courier was, “certain to reopen the debate over practices that many have equated with torture.”

That entire story was more disinformation. In fact, none of the detainees had divulged the actual identity of bin Laden’s courier – or even the courier’s alias within the organization, Sheik Abu Ahmed al-Kuwaiti. Had any of them provided the actual name of the courier, it would not have taken another four years to discover where that courier – and bin Laden – were living. Reuters, which originally reported that KSM had given up the name of the courier, later corrected the story, explaining in a note appended to it that KSM had divulged only the, “existence of courier rather than the name of the courier.” None of the other outlets that had published the disinformation published a similar correction.

Another story, leaked by the CIA to Associated Press, claimed the discovery of the Abbottabad compound as the result of an electronic intercept. In August 2010, according to the story, a voice was heard in a phone conversation with someone whose cell phone US intelligence was monitoring, and from the substance of the conversation, intelligence analysts concluded that it was Kuwaiti. That in turn led CIA operatives to the Abbottabad compound, according to the story.

But is doubtful that Kuwaiti used his mobile phone to communicate with anyone who was already under surveillance in 2010. By 2008, al-Qaeda in Iraq had been largely destroyed, in large part by the US Special Forces’ ability to monitor the Iraqi militants’ use of mobile phones, and both the al-Qaeda shura and bin Laden himself were even more acutely aware of the danger of any electronic communications that could expose Kuwaiti. Documents retrieved from bin Laden’s Abbottabad homereminded al-Qaeda officials that all internal communications were to be by letter only and not by phone or the Internet. Three ISI investigators told Qadir in three separate meetings the same thing about al-Qaeda’s caution with respect to the use of cell phones for internal communications.

Furthermore, it was another six months before the CIA initiated an effort to penetrate the Abbottabad compound with a human source. It was only in February 2011 that the CIA enlisted a Pakistani doctor named Shakeel Afridi to try to gain access to the house on the pretense of a fake campaign for testing people’s blood for hepatitis, according to Afridi’s testimony to ISI investigators. That gap in the timeline is only one of several pieces of evidence indicating that the CIA had not, in fact, tracked someone they believed to be bin Laden’s courier to the compound in Abbottabad in July or August 2010. The story of the intercepted phone call appears to be at least another misleading report on the path to Abbottabad.

The ISI Reveals a Secret

For nearly a year, Pakistan’s intelligence agency, the ISI, remained silent about how bin Laden had been found. Meanwhile, former CIA director Panetta suggested that the ISI had long known about bin Laden’s presence in Abbottabad, two unnamed ISI officials asserted to The Washington Post in an April 27 article that ISI provided the CIA with the cell phone number that belonged to Kuwaiti in November 2010 and told them it was last detected in Abbottabad. But the ISI officials said that their agency did not know at the time that the number was Kuwaiti’s.

A US official denied to the Post that the United States had learned about the number from the ISI. But in the initial briefing of reporters after the bin Laden raid on May 2, 2011, a “senior intelligence official” had actually confirmed, in guarded terms, that Pakistan had provided crucial information that intensified the CIA’s focus on the Abbottabad compound. “The Pakistanis did not know of our interest in the compound,” said the official, “but they did provide us information that helped us develop a clearer focus on this compound over time…. [T]hey provided us information attached to [the compound] to help us complete the robust intelligence case that … eventually carried the day.”

It is now clear that this acknowledgment, which was ignored in media coverage of the briefing, was a reference to ISI’s providing the CIA with both the cell phone number of Arshad Khan and the fact that it belonged to the owner of the compound in Abbottabad. The unnamed official was confirming indirectly that until ISI had given it that information, the CIA had not focused on the Abbottabad compound as the likely location of bin Laden’s courier, or, therefore, of bin Laden himself.

But there was more to the ISI information. Qadir was able to obtain a detailed account from ISI officers involved in the bin Laden investigation showing that ISI also told the CIA that it suspected that Khan might be linked to terrorism.

Qadir is a retired infantry officer who never worked in intelligence, but one of the officers involved in the ISI investigation of the background to the bin Laden killing had been under his command in Kurram Agency many years earlier. That connection enabled him to get access to several other ISI officers who were working on the investigation or were familiar with it. In conversations with Qadir in an ISI safe house in mid-December and over lunch at the Islamabad Club the same month, his initial ISI source told him how the ISI detachment in Abbottabad had launched an investigation of Khan in 2008.

According to Qadir’s initial ISI source, Khan had let it be known locally that he had made some money from business ventures in Dubai, and that his current occupation was dealing in foreign currency exchange and real estate in Peshawar. “It was merely routine,” the ISI officer emphasized. “We had no suspicions at the time.”

That story put out by Kuwaiti and Khan, which was evidently an effort to explain his regular monthly visits to Peshawar, eventually reached the ISI detachment in Abbottabad. The result was a routine request to the detachment in Peshawar to make an inquiry to confirm the information. After months of methodical checking in Peshawar, the ISI unit there reported that none of the half-dozen Arshad Khans who were money changers was a resident of Abbottabad. The inconsistency was conveyed to ISI headquarters in early 2010, with a request for an expanded search in other towns, according to the ISI sources. A request was then sent to all major cities in Pakistan, just in case somebody had gotten the location of the business wrong.

After more months of routine checking, all ISI stations across the country had reported finding no trace of a Pashtun money changer named Arshad residing in Abbottabad. Furthermore, the Peshawar detachment had learned that Khan had been purchasing prescription drugs during his monthly visits to Peshawar, as Qadir learned from two separate ISI officials involved in the post-bin-Laden-raid investigation. The suspicions of ISI officials were now piqued.

It was in July 2010, after the routine investigation indicated that Khan was not telling the truth about his trips to Peshawar, that the ISI official in charge of the investigation decided that the matter was suspicious enough to bring it to the attention of the Counter Terrorism Wing (CTW) of ISI, according to Qadir’s ISI sources. Those sources told Qadir they believed CTW asked the CIA for satellite surveillance of Khan’s residence in Abbottabad. “I thought it was worth getting satellite coverage and forwarded the request to HQ, after consulting with my officers,” the official who made the decision told Qadir. “It could have turned out to be nothing important, but if there was an important person hiding there, I would look like an incompetent fool.”

The CTW had worked closely with the CIA on capturing al-Qaeda leaders and operatives over the years, and that cooperation remained intact in mid-2010, even as tensions between the two intelligence agencies were rising over the rapid increase in the number of spies the CIA had infiltrated into Pakistan that year, partly to keep tabs on ISI’s relations with the Afghan Taliban and Haqqani network. So, it would not have been unusual for the CTW to bring the results of the investigation of Khan to the attention of the CIA.

Five different junior and mid-level ISI officers – three in the field and two in ISI headquarters in Rawalpindi – told Qadir in separate meetings in August and September 2011 that they understood CTW had decided to forward a request to the CIA for surveillance of the Abbottabad compound.

More senior officers at headquarters claimed to Qadir, however, that they didn’t know about such a request, and at an even more senior level, they denied that such a request had even been made. The pattern of responses by ISI officials is consistent with a political decision by the military leadership to avoid even the slightest cooperation with the United States linked to the killing of bin Laden, according to Qadir. Given popular Pakistani anger about the unilateral US raid that killed bin Laden, even admitting that it had played a role in triggering the surveillance of the house in Abbottabad would have played into the hands of Pakistani groups who wanted to discredit the Army as stooges of the United States. “The mood in Pakistan was ugly,” Qadir explained, “and the GHQ [Army headquarters] and ISI were in the eye of the storm. They felt they had no choice but to be accused of either complicity with the CIA in the raid or incompetence, and they chose incompetence.”

But since Pakistan openly broke with Washington over the US military attack on two Pakistani border posts last November, the Pakistani military has more self-confidence. Under its new chief, Lt. Gen. Zaheer ul-Islam, the ISI has become more “proactive” in responding to negative press coverage, according to the officials who spoke with the Post. The ISI revelation to the Washington Post that ISI had turned over Khan’s cell phone number to the CIA in November confirms the essence of the story Qadir obtained from his sources.

The information obtained from ISI about the Abbottabad compound explains the otherwise mysterious remark by President Barack Obama on the night of the raid. “It is important here to note,” Obama said, “that our counterterrorism cooperation with Pakistan helped lead us to bin Laden and the compound he was hiding in.”

Obama’s insertion of that acknowledgement of the assistance of Pakistani intelligence into his triumphant announcement of the bin Laden killing further confirms the evidence that Pakistani help in focusing on the Abbottabad compound was crucial, but senior CIA officials, assuming the news media would never catch on, had nevertheless done what officials always do if they don’t believe they will be held accountable: they put out false information that made them look good. The lies surrounding the bin Laden killing are one more example of this primary leitmotif of the US national security state in the era of unaccountable permanent war.

Posted by AghaSaad in India, India Hall of Shame, INDIA'S HINDUISM, Makaar Dushman on March 7th, 2013

The world’s longest hunger striker, India’s Irom Sharmila, has been fasting for 12 years to demand the repeal of legislation that gives immunity to soldiers. She has refused to plead guilty to attempted suicide.

Right through the brief court proceedings, the fragile, yet resolute 40-year-old social campaigner looked calm and collected. There was no trace of nervousness on the face of Irom Sharmila, who is often referred to as the Iron Lady of Manipur.

When metropolitan magistrate Akash Jain pointed out that she had attempted to commit suicide when she threatened to fast unto death during public protest in the capital in October 2006, Sharmila was unmoved.

Attempted suicide?

Flanked by her lawyer, a stoic Sharmila replied, “I do not want to commit suicide. Mine is a non-violent protest. It is my demand to live as a human being. I love life. I do not want to take my life. I want justice and peace.”

The case will adjourn in May.

Outside the court, where over 50 supporters of the Iron Lady gathered in support of her campaign, she was vocal and forthright.

“I am just a simple woman. I want to follow the non-violent principle of Gandhiji, the father of the nation. Treat us like him and do not discriminate. Don’t be biased against any human being,” she called out to the Indian government.

“I am taking personal pain to send a message for the improvement of and for a peaceful environment,” she told DW.

Sharmila, who is also a poet and writer, started her fast in November, 2000. Soon thereafter, she was charged with attempted suicide, which is illegal in India, and has since had to be force-fed via a feeding tube through her nose in the northeastern state of Manipur. Under close supervision, she is administered a liquid mixture of protein, carbohydrates and vitamins in the security ward of a government hospital.

Armed Forces Special Powers Act

Her hunger strike began after security forces allegedly shot and killed 10 people, including teenagers, following an explosion on a road outside a village, not too far from her house. The soldiers later claimed they acted in self-defense, but a judicial inquiry found no evidence to support this.

“I know what I am doing and I know what is right and what is wrong,” she said.

The Armed Forces Special Powers Act (AFSPA), which gives the Indian army and paramilitary forces sweeping powers to arrest people without warrants and use force against suspects without fear of prosecution has been the subject of serious debate in recent years.

A draconian law, say civil rights groups

During the height of armed insurgency in the early 1990s, on mere suspicion, people were indiscriminately arrested and sometimes killed at point blank by law-enforcing agencies in the northeast region.

Calls upon the government to abolish the controversial legislation have persisted.

“This is a law which should be scrapped immediately. The government has been dithering on this subject for long and rights violations are mounting,” Seema Misra, a rights lawyer told DW.

Following the outcry from civil rights groups, the government claims it has been trying to revisit AFSPA and build consensus on scrapping some other controversial clauses.

However, the defense ministry and the armed forces have resolutely opposed any amendments.

Ironically, Sharmila’s court appearance comes at a time when here has been a spurt in complaints received by the human rights cell of the army from the northeastern states.

The number of such reports has gone up from 26 in 2012 to 51 in just over two months this year, according to Defence Minister A.K. Antony, who said the government had established a human rights cell in the army to take suitable action with the agencies concerned.

Author: Murali Krishnan

REF

Posted by admin in Roshan Pakistan on March 7th, 2013

The shifting landscape has made the country a hot favourite for the international media.

The shifting landscape has made the country a hot favourite for the international media, with the number of foreign correspondents coming to the country more than doubling in the past decade. According to the Press Information Department, the number of residing-journalists has risen from approximately 130 in 2001 to 250 in 2012 while the number of visiting journalists has risen from 30-40 to nearly 400 as of today. Along with sending reporters to the country, a number of foreign publications also hire local reporters to report news from Pakistan.

Source: Press Information Department, Pakistan

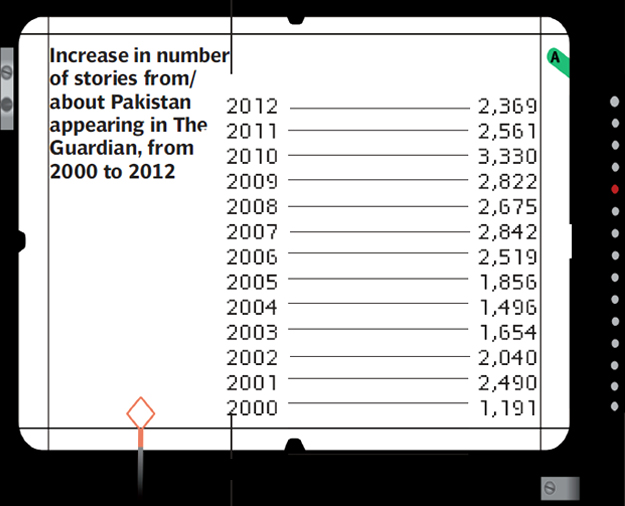

Stories from Pakistan also began to occupy a significant space in most international publications. For example, a search on The Guardian’s website for stories from/about Pakistan shows an increase from 1,191 stories in 2000 to 2,369 stories in 2012.

Source: Press Information Department, Pakistan

A closer look at the nature of the stories reveals that the largest number of stories about Pakistan appeared in the ‘World News’ section, featuring hard news events like terrorist attacks, political developments and international relations while the smallest number of stories appeared in the ‘Law’ section of various international newspapers. The ‘Travel’, ‘Lifestyle’, and other sections featuring soft-stories also contained disproportionately fewer stories.

Source:http://www.guardian.co.uk/search?q=Pakistan+&date=date%2F2012

____________________________________________________________

Watch related videos on Vimeo here:

• Foreign correspondents in Pakistan – Part I

• Foreign correspondents in Pakistan – Part II

• Foreign correspondents in Pakistan – Part III

• Foreign correspondents in Pakistan – Part IV

• Foreign correspondents in Pakistan – Part V

____________________________________________________________

While the coverage of sensitive issues by the foreign media has been applauded for being thorough, credible, and accurate, the range of stories has often been criticised for being too narrow and showing a skewed picture.

“The foreign media writes about issues that people want to read. Some of us might not like what they write, but what they write about the country is fairly realistic and accurate,” says journalist Najam Sethi.

According to Taha Siddiqui, an Islamabad-based journalist reporting for foreign news outlets, such stories are preferred by international editors and tend to get more coverage because they are relevant to the global audience. Given that Pakistan is a nuclear-armed ally in the war on terror, located next to Afghanistan, the country’s stability is a key concern for everyone.

“It’s not actually a bias towards certain stories, but the baggage that comes with the country’s reality,” elaborated Sethi.

Cyril Almeida, assistant editor at Dawn.com, feels that there is not much difference between stories from Pakistan that make headlines in the local media, versus those in the international media. However, he points out that in the case of international publications, not only are stories met with constraints of space and time, but are also competing with stories from across the world. Therefore, a story has to be truly “violent, newsworthy or uplifting” to actually make it to the news pages.

“We should be more concerned about the product [Pakistan], rather than its image. We should fix the product rather than obsess about its image,” he said.

In comparison, Almeida stated that a country like India gets much more coverage by virtue of its size, economic strength and tourist attractions, whereas in comparison there aren’t many feel-good stories to write about in Pakistan these days.

On the other hand, Press Trust of India correspondent Rezaul Hassan, feels that it is not a lack of reporting but certain trends that the international media tends to highlight. He cites the portrayal of fashion shows as a combat mechanism against terrorism in Pakistan as one of the examples of a story that most foreign organisations focused on a couple of years ago.

“But Pakistan is so much more. It is also a country transitioning towards a democratic rule. It is a country where the president has completed his tenure despite all odds. So many young people are determined to make something out of this country despite the problems with the economy and extremism and more needs to be written about all this,” he said.

National Public Radio host and author of “Instant City: Life and Death in Karachi”, Steve Inskeep agrees that the international coverage of the country, while often very good, is too narrow. He states that nearly all of the stories revolve around bombers and the Taliban and the ISI. While those stories are vital, Pakistan has a lot more to offer.

“I do not think that a broader picture of Pakistan would always be more ‘positive’. There are many problems, and many kinds of violence, tremendous poverty, inequality and problems of sustainability and democratic survival. But the picture can be fuller, more interesting and truer,” he said.

However, for foreign reporters, looking for a ‘bigger and broader picture of the country’, and the tedious process of reporting required by such a ‘big picture’, can be particularly challenging due to language barriers, security concerns and complex political and social realities of the country.

While being on the ground is important for journalists, most of them rely on stringers, fixers and interpreters for access to stories in areas like the Federally Administered Tribal Areas. Additionally, stringers can also play an important role in gaining access to sources and help acquire a more accurate understanding of the country’s customs, language and history.

According to Richard Leiby, bureau chief for The Washington Post, the qualities intrinsic to a good stringer are being good-natured, flexible and well-connected.

“Sometimes even a driver can open a window into the local culture and influence a story,” says Inskeep. He narrates his experience of watching cricket over dinner with his driver’s family, which helped him understand the rules and the local fascination with the sport – which gave him a fresh angle from which to view the story.

Language barriers

Lack of knowledge of Urdu and other local languages can often create difficulties in communicating with sources. Stringers and translators can be particularly helpful in such situations.

According to Inskeep, the only solution was to ask questions, and keep asking them till you were clear about an issue.

“While some people seemed suspicious and did not say all they knew, others were delighted to share their stories. No matter where you are in the world, if you are willing to listen, you hear the most amazing things,” he said.

Hassan recalls how people initially assumed his Urdu/Hindi skills to be perfect, since he belonged to India. This was far from the truth back then. But now, he claims that he can speak these languages as well as the locals.

He describes his term in Pakistan as one of the most “fertile periods” of his professional life but the journey has not been equally satisfying in personal terms. Restrictions on travel frustrate him the most.

Being one of the only two Indian journalists working in Pakistan currently, he has often encountered great trouble while getting visa extensions.

“There are times when I have been without a visa for up to six months,” he said, adding that it was unfortunate that such hindrances existed on both sides of the border.

“We try and look for stories that are different from ‘the story’ that everyone else is writing about,” says Michele Leiby, also a correspondent for The Washington Post.

But that is not always easy given the restrictions on foreign correspondents when it comes to travelling freely outside Islamabad and Punjab. Huge amounts of paperwork is required for such travels, which consumes a lot of time, often at the cost of dropping a story.

While talking to the average Pakistani, or getting really close to a story might be challenging for foreign reporters due to security reasons and language barriers, access to important government, military and bureaucratic officials is often easier.

“Pakistani political leaders and officials are sensitive, I think, about the image their country presents to the world, so they tend not to totally ignore calls,” says Leiby.

Hassan, who has faced unusual difficulties in getting information from the government, shares a completely different opinion. “There are people who flatly refuse to talk to you, or even share the more harmless kind of information, simply because you are Indian,” he said.

Reporting for a foreign publication also allows for a certain level of freedom and fearlessness in stories – a rare luxury for local reporters. While local journalists might have better access, the deteriorating security situation for journalists in the country prevents them from actually covering those stories, elaborates Rob Crilly, the Pakistan correspondent for The Telegraph. He cites stories on Balochistan, blasphemy, religion and the workings of ISI as some of the dark corners upon which foreign reporters can tread relatively freely.

“We work here as if we were working in the United States. We are not under risk of being abducted, jailed or censored. The worst that can happen to us for doing these stories is that we will get kicked out,” says Leiby in agreement.

The threat to journalists in Pakistan applies more to local reporters rather than to us and I have immense respect for men and women here who continue to do their job despite such difficulties, added Mrs Leiby.

Covering Pakistan: the experience

“Spend two weeks in Pakistan: you are confused. Spend one year in Pakistan: you are more confused,” says Leiby, who has been in the country for the past one year along with his wife.

He added that the cultural adjustments would “blow your mind away”, if one did not have any previous experience of working in the Muslim world. For Leiby however, the adjustment was not so drastic due to his previous assignments in Gaza, Iraq and Egypt.

“My major perception adjustment was to the idea that everyone would hate me as an American. That is indeed far from the truth,” he explains how some of his pre-conceived myths were dispelled upon arrival.

There were exceptions like the time he stepped out to the nearby petrol station to get a few quotes for a story where someone inquired what branch of the Central Intelligence Agency he belonged to. When he responded, “No sir, I work for the Washington Post,” the man retorted: “Isn’t that the same thing?” Leiby recalls with a laugh. Such incidents however, are an exception rather than the norm, he added.

But the suspicion towards British reporters is lesser, which makes the job relatively easier for them, as compared to an American reporter or one from any other European country, says Crilly. Having worked here for the past two and a half years now, he recalls the transition as a “relatively easy one”.

“You can say a lot of bad things about the British Empire but one of the things it has done is give us a common language, a mutual love for cricket and a cup of tea. That has opened doors for me in many ways,” he said.

For an Indian journalist, covering Pakistan is “a dream job”, says Hassan who has been doing so for the past five years. For him the choice of working here was extremely straightforward as the country figures prominently in Indian politics and diplomacy and people back home love reading about it. However, there was much warning from fellow countrymen for these journalists before they came to Pakistan about the unstable security conditions and people from agencies following him around.

On their first night in Pakistan, Hassan and his wife returned to their hotel safely late at night. Despite all they had heard, the couple decided to go out and discover for themselves. “Such small things highlight the difference between perceptions and reality,” he said.

For Michele Leiby, the surprise came at the sight of armed men and the abundance of weapons everywhere.

“Initially, I was surprised to see even the guard outside a Nando’s (a foreign food chain) outlet holding a gun. But with time, you get used to these things,” she added with a smile.

Her husband recalls the first sound of gunshots he heard in the country, which were later discovered, to his amusement, to be part of a wedding celebration around the street corner.

A hospitable people

The warmth and generosity of the Pakistani people struck a chord with all foreign correspondents. “Wherever you go, there is a cup of tea, often accompanied by an invitation to lunch. The hospitality still overwhelms me,” says Crilly.

Michele Leiby also feels that she has learnt the true meaning of warmth and hospitality through the people in Pakistan. She fondly recalls a family in the refugee camps in Jalozai, who opened their hearts and homes to them despite having nothing aside from their tent, a cot, and a few pigeons.

Despite the warnings and potential bumps and dead ends, the ride for a foreign journalist reporting in Pakistan is an exhilarating one. “You come to Pakistan, it feels like you are driving at 80 miles/hr every day. When you go back home, you go back to driving at 20 miles/hr. It is such an incredible rush being here”, says Hassan.

Strange tales from Pakistan

Pakistan Loving Fatburger as Fast Food Boom Ignores Drones – Published in January 2013 byBloomberg, this article traces the growth of American franchises and increase in consumer spending in Pakistan over the past few years. However, the headline and the parallels drawn between enjoying food at American chains and terrorism drew a large amount of criticism, especially over social media

Bin Laden City Abbottabad to build amusement park: Published in AFP on February 2013,the story is about the government plans to build an amusement park in the city of Abbottabad. However, the reference to Abbottabad as “Bin Laden City”, has been criticised for limiting the city’s history and identity to the final refuge of a terrorist.

In Pakistan, underground parties push the boundaries – Published in August 2012 byReuters, this report juxtaposes the culture of partying, drinking and dancing by young people against a backdrop of rising extremism and Talibanization in Pakistan. It received a lot of criticism for misquoting sources and drawing parallels between two exaggerated extremes in the country.

Designers shrug off militant violence for Pakistan’s fashion week: A series of stories ran in 2009 in several foreign newspapers, covering Pakistani fashion weeks and portraying it as an alternative mechanism for combating the increasing extremism in the country. This kind of coverage received criticism for juxtaposing two different extremes with each other.

Stories covered exceptionally well by foreign media

1. Osama bin Laden’s death: How it happened: The level of detail, precision and openness in the reporting on the bin-Laden operation by the foreign publications remains unmatched by local newspapers. The shortcomings of the ISI and the Pakistani army have also been addressed openly, a subject that remains sensitive for local papers.

2.Karachi:Pakistan’s bleeding heart: A detailed story on the violence in Karachi, incorporating perspectives from the various stakeholders and mapping out the various sectarian and political clashes in the city.

3. Pakistan’s secret dirty war: The piece sheds light on the conflict in Balochistan, the issues of missing persons and the insurgency in the area. The reporting in the story was extremely detailed and highlighted an important issue in the country, mainly ignored by mainstream media at the time.

4. Cheating spouses keep Pakistani private detectives busy: An unusual and different story detailing the woes of women in Pakistan, who hire detectives to keep track of their spouse’s whereabouts and activities. The story breaks free of the usual pattern of terrorism and bombs and chronicles the dilemmas of an average Pakistani.

5. In Pakistan’s Taliban territory, education is a casualty of conflict: A profile of a school in Waziristan which continues to function despite all odds, the story offers a unique perspective into the area, unlike the usual tales of bombs and destruction that emanate from the region.

(WITH ADDITIONAL INPUT FROM VAQAS ASGHAR, WAQAS NAEEM AND FARMAN ALI)

Published in The Express Tribune, February 24th, 2013.

Posted by admin in Defense, Pakistan Air Force on March 4th, 2013

|

|

The J-10 multi-role fighter approaches Western fighters in terms of performance and capabilities |

The J-10 Sale Epitomizes Strategic Alliance

The deal marks the depth of a strategic alliance between Beijing and Islamabad. Some reports suggest that Pakistan is actually seeking 150 J-10 fighter jets, which go by Chengdu Jian-10 in China and F-10 in Pakistan, for a sum of $6 billion (The Hindu, November 11). The Pakistani government, however, dismisses such reports as inflated (Financial Times, November 10). Although Pakistan has not yet made the deal public, its prime minister, Yousaf Raza Gilani, on November 23, confirmed that “his country is in talks with China for securing the J-10s” [1]. Pakistan turned to China for these aircraft in 2006 after it failed to secure the F-16s from the United States (Dawn, May 1, 2006). General Pervez Musharraf, Pakistan’s former military ruler, who negotiated the deal during his visit to China in 2006, is the real architect of this grand sale (The Hindu, November 11).

The J-10s are China’s third generation fighter aircraft that it has indigenously developed (The Hindu, November 11) and manufactured at the Chengdu Aircraft Industry (CAI). Some observers, however, believe that J-10s are China’s fourth generation aircraft. “This aircraft is a cousin to the Israeli Lavi (upon which it is based) and roughly equivalent in capabilities to the U.S. F-16C flown by several air forces around the world” (See “China’s Re-emergence as an Arms Dealer: The Return of the King?” China Brief, July 9). The J-10s started development in the mid-1980s and finally entered production for the People’s Liberation Army Air Force (PLAAF) about three or four years ago. Aviation experts rank them below the F-16s, the Swedish Gripen and other smaller combat aircraft (China Brief, July 9). According to a report in The Hindu (November 11), China is working on developing its fourth generation fighter jets as well. The United States, The Hindu report further claims, is the only country that possesses a fourth generation combat aircraft—the F-22s. Yet aviation experts believe the F-22s are fifth generation fighter jets. Chinese Deputy Commander of the PLAAF General He Weirong claimed that “China would operationalize its very own fourth generation aircraft in the next eight or ten years” (The Hindu, November 11). The Chinese official further claimed that the fourth generation planes would “match or exceed the capacity of similar jets in existence today” (The Hindu, November 11).

In anticipation, China is also training Pakistani fighter pilots for flying the fourth generation combat aircraft. On January 16, it delivered eight Karakoram K-8P trainer jets to Pakistan for this purpose. According to an official statement, the K-8P jets had enhanced the basic training of PAF pilots and provided a “potent platform for their smooth transition to more challenging fourth generation fighter aircraft” (The Asian Defence, January 16). The K-8P is an advanced trainer jet that has been jointly developed by China and Pakistan. It is already in service at the PAF Academy. At the handing-over ceremony for the K-8Ps, a visiting Chinese delegation as well as high-ranking PAF officers were in attendance.

China’s sale of the J-10 fighters to Pakistan, however, signals the depth of its strategic alliance with Pakistan. Pakistan will be the first country to receive the most advanced Chinese aircraft, which speaks volumes to Chinese faith in its strategic partnership with Pakistan. Defense analysts, however, believe that the sale sends an important message to the world that China’s “defense capability is growing rapidly” (Financial Times, November 10). China-Pakistan military relations spanned over 43 years, starting in 1966 when China provided Pakistan with F-6s, which were followed by the successive supply of such aircraft as FT5, A5, F-7P, F-7PG and K-8 (Jang, November 22).

These relations continue to grow with high-level exchanges in the defense sector. As recently as October of this year, Chinese Vice-Minister Chen Qiufa, administrator of China’s State Administration for Science, Technology & Industry for National Defense (SASTIND), led a delegation of Chinese defense-companies to Pakistan. He called on Prime Minister Gilani and discussed cooperation in the JF-17 Thunder Project, Al Khalid tank, F-22 frigates, Airborne Warning and Control System (AWACS), and aircraft and naval ships (APP, October 17). The Chinese delegation included representatives from China’s missile technology firm Poly Technologies as well as Aviation Industries Corp. of China, China Shipbuilding Industry Corporation, China Electronics Technology Group and China North Industry Corporation.

Although there is a proliferation of joint defense projects between China and Pakistan, their collaboration in aviation industry has peaked at the turn of the millennium. The mainstay of their joint defense production is the Pakistan Aeronautical Complex (PAC) in Kamra (Punjab), which services, assembles and manufactures fighter and trainer aircraft. The PAC is rated as the world’s third largest assembly plant. Initially, it was founded with Chinese assistance to rebuild Chinese aircraft in the PAF fleet, which included Shenyang F-6 (now retired), Nanchang A-5, F-7 combat aircraft, Shenyang FT-5 and FT-6 Jet trainer aircraft. The PAC also houses the Kamra Radar and Avionics Factory (KARF), which is meant to assemble and overhaul airborne as well as ground-based radar systems, electronics, and avionics. The KARF, which is ISO-9002 certified, has upgraded the PAF Chengdu F-7P interceptor fleet. Over time, the PAC has expanded its operation into aircraft manufacturing, and built a specialized manufacturing unit in the 1980s: The Aircraft Manufacturing Factory (AMF). The AMF got noticed in the region when it partnered with the Hongdu Aviation Industry Group of China to design, develop and coproduce the K-8 Karakoram (Hongdu JL-8), which is an advanced jet trainer. The AMF’s flagship project, however, is the Sino-Pakistani joint production and manufacture of the JF-17 Thunder aircraft, which it is producing with the Chengdu Aircraft Industry (CAI).

JF-17 Thunder Makes Over the PAF

In recent history, China and Pakistan set out for the joint production of JF-17 combat aircraft that both countries consider a substitute for U.S. F-16s. Pakistan’s indigenous manufacture of the first JF-17 (which goes by FC-1 in China) came to fruition on November 23, when Pakistan Aeronautical Complex (PAC), an arm of the Pakistan Air Force, turned it over to the PAF to the chants of “Long Live Pak-China Friendship” (The News International, November 24).

Pakistan’s Prime Minister, Pakistan Chief of Army Staff and Chinese Ambassador to Pakistan, Lou Zhaohui, were among the dignitaries who attended the handing-over ceremony. Chinese Ambassador Zhaohui, speaking on the occasion, told his audience: “China wants to further broaden the defense cooperation with Pakistan” (Jang, November 23). The PAF already has 10 JF-17s, which were produced in China, in its fleet. The JF-17 project began in 1992, under which China agreed to transfer technology for the aircraft’s joint production. The project was hampered in 1999, when Pakistan came under proliferation sanctions. It gained momentum in 2001.

On September 3, 2003, its prototype, which was manufactured in China, conducted the first test flight. The PAF claims that the JF-17s, with a glass cockpit and modern avionics, are comparable to any fighter plane (Jang, November 23). It is a lightweight combat jet, fitted with turbofan engine, advanced flight control, and the most advanced weapons delivery system. As a supersonic plane, its speed is 1.6 times the speed of its sound, and its ability to refuel midair makes it a “stand-out” (Jang, November 23). Pakistan intends to raise a squadron of JF-17s by 2010. The Chief of Air Staff of the PAF told a newspaper that JF-17s would help “replace the existing fleet of the PAF comprising F-7s, A-5s and all Mirage aircraft” (The News International, November 8). Eventually, Pakistan will have 350 JF-17s that will completely replace its ageing fleet.

Pakistan also plans to export these aircraft to developing countries for which, it says, orders have already started pouring in (Jang, November 22). China and Pakistan anticipate an annual export of 40 JF-17s to Asian, African and Middle Eastern nations [2]. At $25 million apiece, the export of 40 aircraft will fetch them $1 billion per year. There are estimates that Asia will purchase 1,000 to 1,500 aircraft over the next 15 years. In this Sino-Pakistani joint venture, Pakistan will have 58 percent of shares, while China will have 42 percent (The News International, November 25). Besides defense aviation, China and Pakistan are closely collaborating on the joint production of naval ships as well.

Chinese Frigates for the Pakistan Navy

China and Pakistan worked out a $750 million loan to help Pakistan build four F-22P frigates (The News International, September 16, 2004). In 2004, Pakistan negotiated this non-commercial (i.e. low-cost) loan with China for the joint manufacture of naval ships. China and Pakistan have since moved fast to begin work on this project. They have now expanded the original deal to build eight F22P frigates respectively at Hudong Zhonghua shipyard in Shanghai, China, and Karachi shipyard and Engineering Works (KSEW), Pakistan. The manufacturing cost of each F22P Frigate, which is an improved version of China’s original Type 053H3 Frigate, is $175 million. At this rate, the cost of eight frigates will run at about $1.4 billion.

The first Chinese-built F-22 frigate, named PNS Zulfiqar (Arabic for sword), was delivered to Pakistan on July 30 (The Nation, July 31). A month later, the ship was formally commissioned in the Pakistan Navy fleet in September. Soon after its arrival in July, the ship participated in the Pakistan Navy’s SeaSpark exercises. Of the original four frigates, three were to be built in China and one in Pakistan (Asia Times, July 11, 2007). After the delivery of PNS Zulfiqar, the remaining two ships that are being built in China are expected to be commissioned in the Pakistan Navy fleet by 2010. The fourth ship being built in Pakistan’s Karachi shipyard will be ready by 2013 (Asia Times, July 11, 2007).

The Pakistan Navy describes the F-22P frigate as a Sword Class ship that is equipped with long-range surface-to-surface missiles (SSM) and surface-to-air missiles (SAM), depth charges, torpedoes, the latest 76mm guns, a close-in-weapons system (CIWS), sensors, electronic warfare and an advanced command and control system (The Nation, July 31). The ship has a displacement of 3,000 tons and carries anti-submarine Z9EC helicopters. China has already delivered the first batch of two such helicopters to Pakistan. Although the Pakistan Navy has Sea-King helicopters for anti-submarine operations, it is now acquiring Chinese Z9ECs to enhance its operational capabilities (The Nation, July 31). In addition to building eight frigates, the Sino-Pakistan defense deal includes the upgrading of the Karachi dockyard for indigenous production of a modern surface fleet. The frigates deal is the first of its kind between China and Pakistan, which forges their two navies into a high-level collaboration for boosting their surface fleet.

Conclusion

At the turn of the millennium, China and Pakistan have diversified their defense trade into joint defense production. They have since been collaborating on the production of most advanced weapons systems, such as the JF-17s combat aircraft and F-22P Frigates. Pakistan will receive the transfer of technology for the J-10s as well. China recognizes that Pakistan is rich with human capital in the high-tech defense industry, which serves as a magnet for its investment. Both China and Pakistan look to capture wider defense export markets in Asia, Africa and the Middle East. At the same time, their growing cooperation in aviation and naval defense systems signals an important shift in Pakistan’s military doctrine that traditionally favored Army (especially ground forces) over its sister services—Navy and Air Force. In the region’s changing strategic environment, in which China has growing stakes, Pakistan has come to recognize the critical importance of air and naval defense. The China-Pakistan collaboration in aviation and naval defense amply embodies this recognition.

Notes

1. “NRO beneficiaries will be held to account.” Daily Intekhab, dailydailyintekhab.com.pk/news/news10.gif.

2. Tarique Niazi, “China-Pakistan Relations: Past, Present and Future,” A presentation made at the Woodrow Wilson International Center for Scholars on January 29, 2009.

The J-10 multi-role fighter is the first Chinese-developed combat aircraft that approaches Western fighters in terms of performance and capabilities. Development of the J-10 began in 1988. It was intended to counter threat posed by the Soviet forth-generation fighters – the MiG-29 and Su-27. The J-10 was initially planned as an air-superiority fighter, however collapse of the Soviet Union and changing requirements shifted the development towards a multi-role fighter. Aircraft made it’s maiden flight in 1998. The whole project was kept under high secrecy. It is worth mentioning, that the first photos of the J-10 came out only 3-4 years after the first flight. Some sources claim that it was influenced by the IAI Lavi. The J-10 multi-role fighter entered service with Chinese air force in 2004, however it was first publicly revealed only in 2006. Currently around 240 of these aircraft are in service. It is estimated that 300 fighter of this type will be required for Chinese air force and possibly naval aviation too. A number of countries, including Indonesia, Iran, Pakistan and Thailand shown interest in purchasing this aircraft. The J-10 has a single engine. The first batch of about 50 aircraft is powered by Russian AL-31FN turbofan engines. This batch was delivered to Chinese air force between 2004 and 2006. An indigenous Taihang turbofan is under development. The J-10 has beyond visual range air combat and surface attack capabilities. Aircraft has 11 external hardpoints for a range of weapons. Alternatively it can carry target acquisition, navigation pods or auxiliary fuel tanks. It is worth mentioning that the J-10 has an in-flight refueling capability. The main armament on the air-superiority missions are the PL-12 medium-range active radar-homing air-to-air missiles. For close ranges it carries the PL-8 infrared-homing missiles. For surface attack role the J-10 carries up to six 500-kg laser-guided bombs, free-fall bombs or 90-mm unoperated rocket pods. Aircraft is also completed with a single-barrel 23-mm cannon. The J-10 is fitted with an indigenously designed pulse-doppler fire control radar. It is capable of tracking 10 targets simultaneously and attacking 4 of them. Estimated maximum detection range is 100 km. Aircraft is fitted with a fly-by-wire system. A two-seat variant, the J-10S fighter-trainer, is available. It is identical to the single-seat variant, but has a stretched fuselage to accommodate second pilot seat. The J-10S can be used for pilot training or as a standard fighter. This aircraft maid it’s maiden flight in 2003.

Variants

J-10B multi-role fighter, with improved airframe and avionics. It is likely to become a standard production model. |

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

Posted by admin in Pakistan Fights Terrorism, Pakistan-A Nation of Hope on March 4th, 2013

In Pakistan’s isolated Naltar Valley the Pakistani Air Force is training children who learned to ski on wooden planks tied to boots with wire for the 2014 Winter Olympics.

By Annabel Symington, Contributor / March 3, 2013

Members of the Pakistani Air Force march past the mausoleum of Muhammad Ali Jinnah during Defense Day ceremonies, or Pakistan’s memorial day, in Karachi, Pakistan, September 2011. In the isolated Naltar Valley, home to one of two ski slopes in the country, the Pakistani Air Force is training children who learned to ski on wooden planks tied to boots with wire for the 2014 Winter Olympics.

Akhtar Soomro/Reuters/File

In the isolated Naltar Valley, home to one of two ski slopes in Pakistan, children who learned to ski on wooden planks tied to boots with wire are being trained for the Winter Olympics by the Pakistani Air Force.

Whatever the reason, it’s brought opportunity and Olympic dreams to a small remote community in Pakistan that wouldn’t otherwise see it. Skiing has become increasingly popular in the valley since a local boy returned from the Vancouver Winter Olympics, and the Olympic ambitions of the community have swelled with it.

In 2010, Naltar-born, Muhammad Abbas, now 27, became the first Pakistani to qualify for the Winter Olympic Games. He took part in the giant slalom event at the Games inVancouver, Canada, placing 79th out of 81 participants, and returned home a hero.

Like most children in the Naltar Valley, Mr. Abbas learned to ski on homemade wooden skis. Abbas was part of the Naltar Ski School, a program run by the Air Force that offers a full scholarship and coaching to 25 young skiers from the valley each year.

A team of three boys from Naltar is currently in Italy to compete in a qualifier for the 2014 Winter Olympics. They will then fly onto Austria, Turkey, and Lebanon for other competitions, hoping to amass the 140 points needed to qualify for the upcoming Games in Sochi, Russia.

Late last year it looked like budget constraints of the military-funded Ski Federation of Pakistan would keep Pakistan out of the 2014 Winter Olympics. But at a meeting in December 2012 of the Federation’s executive committee and general council, which is made up of the Air Force’s top dogs, participation in the next Winter Olympics was approved and additional budget was allocated by the Air Force.

Abbas is part of the team, along with Mir Nawaz, 19, and Mohammad Karim, 17.

Another four boys from Naltar are also preparing to fly to Tajikistan for the Asian Children Skiing Championship this month. The team includes Noor Muhammad, 14, who has been tipped for Pakistan’s 2018 Winter Olympics team.

Noor dreams of being a professional skier and is determined to get to the Olympics in 2018. When asked what is takes to make a top skier he says simply, “hard work.”

The Naltar Valley lies 25 miles north of the provincial capital Gilgit in northern Pakistan, where the western edge of the Himalayas meet the Karakoram mountain range. The picturesque valley lies deep in snow for much of the year, and is only reachable by jeep along a narrow mountain road – or helicopter.

The valley’s steep sides and powder snow offer perfect skiing conditions. The only other ski destination in Pakistan is in Malam Jabba, Swat, where a ski resort stood until militants destroyed it in 2008.

The Pakistan Air Force introduced skiing to the Naltar Valley – and Pakistan – in the 1960s as part of snow survival training for pilots stationed in the mountainous northern areas of Pakistan and the hostile terrain of the disputed boarder between Indian and Pakistani Kashmir.

The Air Force remains the sport’s chief patron and in 1990, they formed the Ski Federation of Pakistan to extend the reach of skiing beyond military personnel. The ski program has become a way for the Air Force to promote a different Pakistan story.

“We need to focus on reaching international standards and taking part in international competitions,” said Chief of Air Staff Air Marshal Tahir Rafique Butt in a speech at the awards ceremony for the National Ski Championships held in Naltar in mid February. “All that they [the skiers of Naltar Valley] need is the opportunity.”

In addition to the scholarship program, the Air Force bankrolls ski lessons to around 120 children each year. “We take children from the age of 5, but they only play,” says Zahid Farooq, a retired Air Force officer who heads up the ski training program at Naltar, “They start proper lessons at 10 [years old].”

Equipment is limited, and while none of the children in the Air Force’s ski program use wooden skis anymore, the children train in two-hour rotations, swapping skis and boots with the incoming group.

The Air Force declined to comment on how much they expect to spend on sending athletes to the Winter Olympic, or how much they spend on the Naltar Ski program as a whole, but they do foot the bill for the entire venture.

An increasing number of girls are taking part in the ski program. Two sisters from Naltar Valley, Ifrah and Aminah Wali, took part in the first-ever South Asian Winter Games, held in India in 2011. The Games were hyped as the South Asian version of the Winter Olympics. Ifrah won gold for in the giant slalom, and Aminah took silver in both the giant slalom and slalom events.

But the girls haven’t been sent to any qualifying competitions for the Olympics. “We are still waiting and hoping that the federation will send us to the qualifiers too,” says Aminah, “I am happy the men’s team is participating in Europe, it’s very inspiring. But women skiers in Pakistan also have the talent to qualify for the Olympics. It is my lifelong dream too.”

There has been hostility in Naltar toward letting girls ski. Locals say that only “educated parents” are allowing their daughters to join the Naltar ski program – which is dominated by boys – suggesting that barriers for girls remain more firmly in place than most would like to admit.

A third of the children in the program this year are girls – a big increase from last year, according to the Air Force’s media director, Group Captain Tariq.

Mr. Farooq says that attitudes have started to relax since Muhammad Abbas returned from the 2010 Winter Olympics, but he admits that more needs to be done to get girls competing internationally, as well as to encourage girls to take up skiing in the first place – and their parents to let them.

Khuheen Sahab, 10, and Rukhsana Shaheen were allowed by their parents to join the ski school this year. Both wear the traditional shalwar top, a long shirt over their ski pants. Rusksana wears a headscarf, while Khuheen covers her head with a wooly hat. Rukhsana says that she would like to be able to ski all the time. “It makes me feel free,” she says.

Another challenge to Pakistan taking part in international events is that many of the children lack the necessary documentation that proves their exact ages, a requirement of international competitions. Children such as Rukhsana are put in classes based on their ability and an estimate of their age, but often don’t know their own ages.

“We are trying to train the children in the appropriate age categories,” says Farooq, “But many don’t have any documents.” According to him, 32 of the 117 children who trained this year could not prove their age.

The valley was once a popular tourist destination with both Pakistani and foreign tourists. But tourism has all but dried up in the past decade as Pakistan’s international reputation has become increasing tied up with terrorism. As tourism declined, so did the main source of income for many of the villagers.

The expanding ski school has helped counter that. The ski facilities now provide employment to around 30 men who groom and maintain the slope for the ski school. The work is seasonal, but there are plans to improve the facilities at Naltar, add a chairlift, and open the resort to tourists, further boosting employment opportunities. Locals (and the Air Force) hope the tourists will come to ski in the winter and hike in the summer, and rekindle the tourist industry in the valley.

Farooq dreams that Naltar will become a ski hub, and that they will eventually be able to host international competitions, further raising Pakistan’s profile on the ski scene.

But, for now he’s focused on opening Naltar to tourists next season, which starts in December.

“The Air Force has sponsored skiing for many years, and now I want to open it up to the general public,” says the Chief of Air Staff Air Marshal Tahir Rafique Butt.

The TV close by plays images of the latest deadly attack on Hazara Shias in Quetta byLashkar-e-Jhangvi, a Sunni militant group. The air staff official looks at the screen and pauses.

“We can avoid militancy by exposing youth to positive activities, like skiing,” he says, “We need a positive international reputation.”

“We can avoid militancy by exposing youth to positive activities, like skiing,” he says, “We need a positive international reputation.”