Imran Ahmad Khan Niazi, 59 years old, currently of Bani Gala village on the outskirts of the Pakistani capital of Islamabad, is certain of many things. He is certain that “a huge change” is coming to his country. He is certain, too, that a “revolution” is on its way. And even if he does not state it explicitly, he is certain that he will, within eight months to a year, win a landslide victory in elections to become Pakistan‘s prime minister. “When we are in power”, he says these days, not “if we were in power”.

When I arrive, Khan is sitting alone at a table in the garden of the house where he has lived since 2005. It is mid-afternoon, but the sun is low and the light is already fading. The house, built as a family home when he was still married to Jemima Goldsmith, sits on the crest of a ridge and commands a view of the foothills of the Himalayas, a large shimmering lake and the city of Islamabad. He is dressed entirely in black, working his BlackBerry.

The house has become part of Khan’s political persona. There is the short journey through the increasingly scruffy villages and then up to the beautiful hacienda-style house with the dogs, the lawns, the swimming pool and the view. There is the image of the politician who currently leads all polls in the country, looking down from his hilltop on the city and the power that he seems set to seize. The vision of the uncorrupt outsider eyeing the distant den of iniquity that he is set to purge is simply too neat to ignore.

Consciously or otherwise, Khan does nothing to undermine the impression. He leads me briskly down to the edge of his land, steps up on to a large boulder overhanging the steep slope and points out the park which he saved from illegal development, and the new houses scattered across the shores of the lakes that are getting closer and closer to where we are standing. “Look at it,” he says angrily. “There is no planning, no planning at all.” He flings an arm out towards the serrated ridge of hills along the horizon. For, along with the certainty, there is righteous anger. This is directed at a number of different targets: a “corrupt political elite” who “plunder” Pakistan; strikes by American missile-armed unmanned drones against suspected Islamic militants near the Afghan frontier; the local “liberals” who condone the strikes; the lack of electricity crippling the country’s economy; imperialists of old and neo-imperialists of today; the war on terror and its attendant human-rights abuses; multinational lending organisations; Washington; rich Pakistanis who avoid tax while their countrymen live in “multi-dimensional deprivation”.

In Pakistan today, certainty and anger make a potent mix. The country, chronically unstable if astonishingly resilient, is not only suffering ongoing extremist violence but also terrible economic problems which are steadily wiping out any gains in prosperity made in previous decades. Over recent months Khan has held a series of huge political rallies, with crowds numbering more than 100,000. In terms of popularity at least, Khan and the party he founded 15 years ago, the Pakistan Tehreek-e-Insaf (Pakistan Union for Justice), have made a major breakthrough.

In the brutal world of south Asian politics – where dynasties, patronage and frequently sheer muscle count more than policies or public support – this is a genuine achievement. In 1999 I spent several days with Khan and his partyworkers on the campaign trail in eastern Pakistan. The headline on my pessimistic piece was: “No Khan Do”. These days few would risk such glib assessments of Khan’s electoral chances.

The late 1990s, when Khan was making his political debut, were a raw time. The political scene in Pakistan was dominated by Benazir Bhutto, one of the most celebrated female politicians in the world, and her local rival, Nawaz Sharif. In 1999 the army stepped in through a bloodless and broadly popular coup. I saw Khan on and off occasionally over the subsequent years, but there was little to indicate that my earlier analysis was wrong. He was a legend in sporting terms – one of the best all-rounders in cricketing history – and increasingly well-thought of as a philanthropist, without doubt, but not a serious politician. A column in a local English-language political magazine relentlessly satirised the ambitions of “Im the Dim”, and few disagreed.

The late 1990s, when Khan was making his political debut, were a raw time. The political scene in Pakistan was dominated by Benazir Bhutto, one of the most celebrated female politicians in the world, and her local rival, Nawaz Sharif. In 1999 the army stepped in through a bloodless and broadly popular coup. I saw Khan on and off occasionally over the subsequent years, but there was little to indicate that my earlier analysis was wrong. He was a legend in sporting terms – one of the best all-rounders in cricketing history – and increasingly well-thought of as a philanthropist, without doubt, but not a serious politician. A column in a local English-language political magazine relentlessly satirised the ambitions of “Im the Dim”, and few disagreed.

Now Bhutto is dead, assassinated on 27 December 2007 by Islamic militants, and the old guard of politicians who have survived her, including her husband Asif Ali Zardari, president since 2008, are detested. Khan says he could take over – democratically, of course – at any moment, but he is biding his time. “We have the power to go out and block the government on any issue. But we will only have one chance and we have to be completely prepared.” Back in the late 1990s, he tells me, politics was “like facing a fast bowler without pads, gloves or a helmet”. Not any longer, he says.

Khan was born on 25 November 1952 into a wealthy and well-connected family in Lahore, Pakistan’s eastern city. Ethnically he is a Pashtun, or Pathan, as British imperialists called the peoples concentrated along what once was known as the North-West Frontier. Educated at Lahore’s Aitchison College, one of the most exclusive schools in Pakistan, the Royal Grammar School in Worcester and Oxford University, his early years were typical of Pakistan’s anglicised upper classes. Khan reminisces about how his family home, Zaman Park, was surrounded by fields and woodland where he used to hunt partridge. “Now everything is built up; it’s like living next to a motorway,” he says. “The air pollution, noise pollution… It is terrible.”

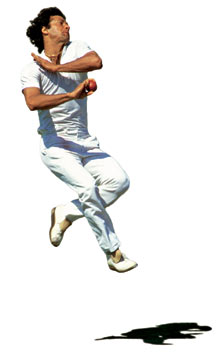

Special delivery: playing at Lord’s in 1987. Khan made his Test debut against England in 1971 aged 18. Photograph: Bob Thomas/Getty Images

Special delivery: playing at Lord’s in 1987. Khan made his Test debut against England in 1971 aged 18. Photograph: Bob Thomas/Getty Images

The shy teenager’s precocious sporting talent took him rapidly into the national side: he made his Test debut against England in 1971, aged just 18. Eleven years later, after performances combining tenacity and flair, he was made captain of Pakistan. Khan’s two autobiographies, All Round View (1992) and Pakistan: A Personal History (2010), both tell the story of his years as an international cricketer: the victories against the odds in front of the home crowd, the career-threatening injury overcome, the return from retirement at the age of 37, winning the World Cup – for the first and only time in Pakistan’s sporting history – despite a ruined cartilage in his shoulder. It is only when in Pakistan, where the sport is a national passion, that the enormity of his sporting achievement is clear.

Neither book is forthcoming about his activities off the pitch, however. A string of rich, well-connected, beautiful women earned him a reputation as a playboy. Then in 1995 he married Jemima Goldsmith, daughter of the late billionaire Sir James Goldsmith. Aged only 21, she converted to Islam and moved to Pakistan. The couple soon had two sons.

“I had always wanted to marry a Pakistani, but I realised while I was playing cricket that sport at that level and marriage were not compatible,” he says. “So I decided I’d only get married when I gave up sport.” Khan twice announced his retirement: the first time, General Zia ul-Haq, then military dictator of Pakistan, persuaded him to reconsider, and the second time he returned to the team to help raise funds for Pakistan’s first cancer hospital. His mother, to whom he wad been very close, had died of cancer in 1984 and in her memory he had decided to build a hospital which would offer free treatment to the poor. “The whole board [of the hospital] said I needed to keep playing so they could raise money. So I carried on until I was 39, and by then I was too old for an arranged marriage. I just could no longer trust someone else to find someone for me.

“So I found it very difficult,” Khan continues. “The irony was I thought all the 25-year-olds were too young, and I was still looking when I met Jemima – and she was 21.” The couple married in 1995 and divorced nine years later. “It would have had a greater chance of working if I hadn’t been involved in politics or she had been Pakistani. Or if she could have got involved in the politics with me.”

As one of his wife’s grandfathers was Jewish, a noxious storm of abuse and conspiracy theories was unleashed. Pakistan is a country where antisemitism is so deep-rooted as to be remarkable only when absent. Local politicians targeted this “weak spot”: spurious court cases, rabble-rousing editorials, underhand smears all contributed to make Pakistan a hostile environment for the young socialite heiress.

The construction of the cancer hospital and the leadership of his party consumed most of Khan’s funds and time. “Because they attacked me and her, calling me part of the Jewish lobby, she couldn’t get involved in politics and that was the beginning of it becoming more and more difficult. And she really gave it her best shot. I look back and think: could my marriage have worked? I think of the words of the prophet [Mohammed]: ‘Don’t fight destiny because destiny is God.’ I believe the past is to learn from, not live in.”

‘She really gave it her best shot’: with his ex-wife Jemima on their wedding day in 1995. Photograph: Nils Jorgenson/Rex Features

‘She really gave it her best shot’: with his ex-wife Jemima on their wedding day in 1995. Photograph: Nils Jorgenson/Rex Features

He still gets on well with her family – when in London he stays with his former mother-in-law Lady Annabel Goldsmith – and has a “fabulous relationship” with his sons. A day or so after we meet, he is flying to London for three days for half term. “It’s very important to spend time together. Children really need a mother and a father. They have different roles, but both are very important. This idea of having two men as parents. It’s a nonsense.”

Religion became important to Khan relatively late. He grew up, he says, surrounded by faith. His mother read him stories from the life of the Prophet Mohammed and at seven he was taught to read the Koran in Arabic by a visiting scholar. But as a young man, he was not devout. The return to faith came following his mother’s illness and a profound personal interrogation, he says, prompted by the furore after the publication of Salman Rushdie’s Satanic Verses. Wanting to defend Islam from what he saw as ignorant attacks, Khan began to read more widely about the religion.

These days his identity as a conservative, but not fundamentalist, Muslim has become part of his political programme and, in a way not often understood in the west, his political persona in Pakistan. Liberals in the country dismiss him as a mullah, literally a low-level cleric but figuratively an ignorant extremist, just, they say, without the beard that is the mark of the pious Muslim man. This, predictably, irritates Khan. His faith, he says, has been influenced primarily by the Sufi strand of Islamic practice, which emphasises a believer’s direct engagement with God without the intercession of a cleric or scholar. Another major influence is Allama Iqbal, a poet, political activist and philosopher who died in 1938 and is considered one of the spiritual fathers of Pakistan. “Iqbal, who is my great inspiration, clashes with the mullahs,” says Khan. “The message of all religions is to be just and humane but it is often distorted by the clergy.”

For all the talk of tolerance, Khan’s party has been keeping some strange company recently, sharing a platform, for example, with the Difa-e-Pakistan or Pakistan Defence Council. This is a coalition of extremist groups which wants to end any Pakistani alliance with the USA and includes people who not only explicitly support the Afghan Taliban but who are associated with terrorist and sectarian violence. At one recent rally of the council in Islamabad, I met members of Sipah-e-Sahaba Pakistan, a Sunni group which has murdered thousands of Shias, while around me hundreds chanted: “Death to America.” Lashkar-e-Toiba, the organisation responsible for the 2008 attacks in Mumbai in India in which 166 died, is also part of the coalition. Mian Mohammed Aslam, the head of the Jamaat-e-Islami, a mass Islamist party similar to the Muslim Brotherhood in the Islamic world and dedicated to a similarly hardline, conservative programme, spoke warmly of “close relations” with Khan, even going as far as raising the prospect of an electoral pact with Khan’s Tehreek-e-Insaf in the coming elections, when I interviewed him.

Khan says that as a politician he and his party need to reach out to everybody, but that does not mean that he endorses the views of the Islamists. Undoubtedly a social conservative who is religious in outlook and rhetoric, he does not lapse into simplistic binary analyses of the west (secular or “Crusader Christian” against Islam) like many of his countrymen. He denies being anti-western at all. “How can I be anti-western? How can you be anti-western when [the west] is so varied, so different? It doesn’t make sense.”

Finger on the pulse: speaking at a rally in Lahore last month. ‘We only have one chance and we have to be completely prepared,’ he says. Photograph: Warrick Page/Getty Images

Finger on the pulse: speaking at a rally in Lahore last month. ‘We only have one chance and we have to be completely prepared,’ he says. Photograph: Warrick Page/Getty Images

It is not religion driving Khan’s anger but something else. Take, for example, his analysis of the violent insurgency in the western borders of his country. For most scholars, this is the result of a complex mix of factors: the breakdown of traditional society, war in Afghanistan in the 1980s and the 2000s, the generalised radicalisation of the Islamic world since 2001, al-Qaeda’s presence, the Pakistani army’s operations in the area and the civilian casualties caused by drone strikes. The militants themselves, who behead supposed spies and drive out development workers or teachers, are increasingly unpopular. Yet Khan calls the violence a “fight for Pashtun solidarity against a foreign invader”. He insists “there is not a threat to Pakistan from Taliban ideology”.

For Khan this foreign invasion takes various forms. There is dress (he speaks admiringly of how the Pashtuns still shun western clothes) and there is TV (he mentions how his former mother-in-law thought one channel beamed in from India was in fact American, because of all its adverts for consumer goods). His charge against the “liberal elite” is implicitly a charge against the most westernised elements in the country. It is a defence of a vision of the local, the authentic, the familiar, against globalisation.

However, with his cultured public-school vowels, his half-British children, his British ex-wife, his success at a game the English invented, it becomes a very personal argument, too. Khan says he first became aware of the effects of colonialism as a teenager. “My first shock was going from Aitchison to play for Lahore. The boys from the Urdu [local language] schools laughed at me… Then in England we had been trained to be English public schoolboys, which we were not. Hence the inferiority complex. Because we were not and could never be the thing we were trying to be.”

Even the memory agitates him. “I saw the elite [in Pakistan] who were superior because they were more westernised. I used to hear that colonialism was about building roads, railways etc… but that’s all bullshit. It kills your self-esteem. The elite become a cheap imitation of the coloniser.” He says that he recently read that after 200 years of Arab rule in Sicily, the court continued to speak Arabic and wear Arab clothes for 50 years after their former overlords had left.

His recent book is full of such references. P34: “Colonialism, for my mother and father, was the ultimate humiliation.” P43: “The more a Pakistani aped the British the higher up the social ladder he was considered to be.” P64: “In today’s Lahore and Karachi rich women go to glitzy parties in western clothes chauffeured by men with entirely different customs and values” – and so on through the 350 pages.

This lays him open to charges of hypocrisy, inconsistency, of being a self-hating “brown sahib” himself, accusations frequently made by the “liberal elite” Khan so detests. Yet Khan’s patriotism, faith and honesty are attractive to many in a chronically unstable country seen as an exporter of extremism and violence, as irremediably corrupt, as “the most dangerous place in the world”.

So, what would Khan do in power? At the moment he is thick on aspiration and thin on practical policy. He would, he says, cut government expenditure and raise tax collection. He would turn the mansions and villas of senior officials – “these colonial symbols” – into libraries or even museums “like after the Iranian revolution” to show the people how the elite lived. He would solve the “energy and education emergencies” and he would “totally pull out of the war on terror”, withdrawing the army from the western border zone and letting “our people in [these areas] deal with the militants themselves”. Whether he could make the country’s powerful military obey such directives – his critics allege he is unhealthily close to the army – is unsure.

As for relations with Washington, his position is clear: “We need to be a friend of American, but not a hired gun,” he says. “We will take no aid from them. We will stand on our own feet, with a fully sovereign foreign policy and no terrorism from our soil.”

Which political leaders does he admire? Recep Tayyip Erdogan, the moderate Islamist Turkish prime minister, he says; Brazil’s Lula da Silva, who forced a better redistribution of his country’s newly generated wealth; Mahathir Mohamad and Lee Kuan Yew of Malaysia and Singapore, two authoritarians. But it doesn’t really matter. If Khan does end up prime minister he will do things his way.

Khan is not “dim”, as the elite who he detests contemptuously say, but is not an intellectual either. He is a politician riding a wave of public disaffection, and that wave might just carry him to power. What he does afterwards is not something he worries about. He will be 60 this autumn. This would only bother him, he says, if he “had nothing to look forward to”. But he is convinced that he does. From his hilltop Khan looks down and says: “This country will go through its biggest change ever. A revolution is coming.”

• This article was amended on 1 May 2013. The original sub-heading wrongly referred to Imran Khan as a Pashtun aristocrat. This has been corrected.