Imran Khan’s toughest test

The former cricketer is a hero to many in Pakistan but must play the innings of his life to become PM

Christina Lamb Published: 5 May 2013

Imran Khan is standing as ‘a man of the people’ (Justin Sutcliffe)

Imran Khan is standing as ‘a man of the people’ (Justin Sutcliffe)

It is a quarter to midnight in Lahore’s Moon Market and Pakistan’s most famous cricketing hero is in an armoured jeep trapped in a sea of young men, desperate to get near him, faces pressed against the glass, shouting “Captain, I love you!”, and waving green and red party flags or cricket bat symbols.

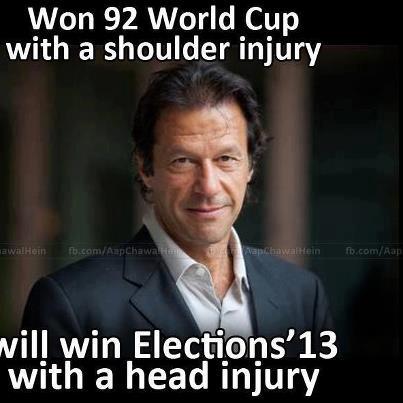

Pakistan may be the most cricket-obsessed nation on earth, but no one is there because of Imran Khan’s cricketing skills. Most look too young to remember him captaining Pakistan to its only World Cup cricket victory in 1992. Instead they hope he will lead them to a very different victory: becoming prime minister after Saturday’s elections.

“This is a revolution!” he declares, as we stare out at the crush of people. “Look at them! They are fed up with the status quo. This is an across-the-board desire for change and a fear the country won’t survive unless we do. It’s middle classes, young people, people who have never voted before, exactly like what happened in the Arab world. We are going to sweep this election.”

Amid the exhilaration, there is also fear. The elections are historic — it will be the first time in Pakistan one elected government will hand power to another rather than be ousted by a military dictator — but also the most violent in the country’s history.

Taliban bombs and shootings have killed 76 people in the past two weeks, forcing many candidates to campaign behind bullet-proof glass far from the crowds; some remotely by Skype; or not at all in the case of Bilawal Bhutto, whose mother Benazir was assassinated five years ago.

Imran, standing as “a man of the people”, will have none of this. Earlier in the day in a dusty field in the far-flung rural district of Narowal, in the northeast of Punjab, where people had left muddy villages and piled on tractors to hear him speak, I watched him exhort supporters to break police barricades and run forward to the rickety stage.

The x-ray machine the crowds had walked through was of no comfort — it was not plugged in. Police hurriedly wheeled in a mobile phone-jammer that nobody could work.

Now we are stuck in a car in a narrow street in a bazaar where three years ago 50 people were killed in a suicide attack. There were no security checks getting into his rally even though Imran says security forces are on “red alert”.

Any one of the men surrounding the car could be a suicide bomber. The black T-shirted Punjab commandos with “No Fear” printed reassuringly on their backs and AK-47s at the ready are nowhere to be seen. Our only protection is police with wooden sticks.

“There’s no security,” says Imran, shaking his head with horror as he watches the police whack his supporters. “We’re all high-risk targets right now.”

Finally we move, surrounded by flashing police lights and supporters on motorbikes. Imran’s chief of staff — who used to be his bank manager in London — hands round cheeseburgers and Cokes. “Campaigning — no food, no sleep and hardest of all, no time to pee,” Imran says.

Moon Market, where he was forklifted onto a stage of shipping containers covered with carpets amid pounding music and cries of “Imran”, was his eighth jalsa — or rally — of the day. Though at 60, still rakishly handsome, he looks exhausted. Since the campaign was launched three weeks ago, he has campaigned 15 hours every day, crisscrossing the vast country in a rented helicopter, as he belts out speeches demanding an end to “status quo politics”.

“It’s my cricket training which is helping,” he says. Yet the last thing he expected was it to be used in such a cause. “I couldn’t even make a speech to my team when I became captain, I was so shy,” he laughs.

It is an incredible turnaround. Though Imran has been revered both at home and abroad for his cricketing skills, his political ambitions have long been treated with derision: since he founded his party 17 years ago, it has held only one seat in parliament. The popular Friday Times newspaper runs a cartoon lampooning him as “Im the Dim”.

Today his crusade against corruption and dynastic politics has clearly struck a chord, making him by far the most popular politician in Pakistan and his Movement for Justice is turning Pakistan’s politics upside down.

But he is up against the formidable political machine of Nawaz Sharif, who was twice prime minister in the 1990s.

And many wonder if the mercurial former cricketer is really the best person to lead this nuclear-armed country, which has become the world’s biggest breeding ground for terrorist attacks, particularly with next year’s deadline looming for the withdrawal of Nato troops from neighbouring Afghanistan.

I first met Imran in the late 1980s when I was living in Pakistan. The Oxford graduate turned cricket star was the country’s most eligible bachelor who every society hostess in Lahore tried to get to their parties, as well as being a fixture on the London nightclub scene.

It was hard to take seriously the idea of him running a political movement, particularly in Pakistan’s entrenched system where many seats are won by feudal lords, whatever party they run for. His own background was hardly ideal, having fathered an illegitimate daughter with the late Sita White, daughter of billionaire Lord White.

To compound things, in 1995 he married another socialite and daughter of a billionaire, Jemima Goldsmith, who, at just 21, was half his age. Though she strove to fit in and they had two sons, the cultural and age differences were vast.

But it was the party he created a year after their wedding that he admitted in his recent memoir really destroyed their marriage. His political pronouncements prompted endless vitriol against Jemima in the Pakistani media, which referred to her as a Jewish heiress.

Things started to change after the attacks in America on September 11, 2001, when he was a lone voice criticising Pakistan’s co-operation with the US — even if the West may question how committed that co-operation was.

A Pashtun, he has become an outspoken critic of drone attacks, arguing that civilian casualties are stoking such resentment that they are driving people to join the Taliban. “The road to peace is to get tribals on your side,” he argues. “Keep bombing them and you push them toward the terrorists.”

Such comments have led him to be seen as anti-West and known as Taliban Khan, labels he angrily rejects. “If you don’t bow to every western politician you should not be termed anti-West,” he says. “I want us to be a sovereign nation not slaves.” He turns the argument that Pakistan is not doing enough to end havens for terrorists back on the West.

“I would ask western countries like the UK to stop allowing money plundered by Third World dictators and politicians to be put in safe havens. It kills more people than terrorists or drugs,” he says. “In Pakistan, 200,000 children die from waterborne diseases which are preventable because these guys have siphoned all the money so there is none for health and education.”

It is widespread disillusion over such misgovernance that has made him so popular. Pakistan’s merry-go-round between military rule and the same corrupt politicians who have looted the country has left it bankrupt. In five years under President Asif Ali Zardari, the country has suffered power cuts of 16 hours a day in Lahore, widespread unemployment, and 25m children not in school. Polio is still endemic.

So great is the frustration that during the Arab spring, Twitter was full of tweets from Pakistanis asking: “When are we going to rise up?”

At Imran’s rally in Narowal, villagers say they are fed up with being neglected. “We have electricity just two hours a day and no gas to cook with as the rich use it for their cars,” said Abdul Reham, a student. “Imran is our last hope.”

It is young people such as Reham that Imran is banking on to sweep him to power. Some 70% of the population is under 35 and 38m of its 85m voters will vote for the first time in these elections.

His appeal is not just to youth. Many women support him. Three of his sisters are out knocking doors as are many Lahori socialites. One group sat with their husbands smoking fat Cohibas outside a coffee bar in Lahore. “We need to help the downtrodden,” said one. “Our servants are getting angry.”

Some American Pakistanis have come over to vote for the first time, too — among them Tahir Effendi, a doctor from New York. “I’m seeing the same energy here as with Obama in 2008,” he said. “It’s ‘Yes we Khan’ instead of ‘Yes we can’.”

Imran is popular, too, with Pakistan’s powerful army, who say they are fed up with cleaning up the mess of the old politicians. They genuinely seem to be keeping out of the elections, leaving some Pakistanis confused. “This is the first time we don’t know who’s supposed to win,” said Shahid Masood, a TV news anchor.

There are numerous other groups, including some extremists and a new party of AQ Khan, the godfather of Pakistan’s nuclear bomb, even though he is supposedly under house arrest for running a nuclear black-market to everywhere from Iran to North Korea. His symbol is a missile.

Yet even Imran’s most committed supporters doubt the enthusiasm he generates will be enough to make his the largest party — let alone give him a majority.

The hurdle is Pakistan’s constituency system in which candidates rather than parties matter — something he has vowed to end since it leads to corruption, even though he has brought in some of “the electables” into his own party.

He has also persuaded new people to stand including Abrar ul-Haq, one of Pakistan’s most famous rock stars, who has ditched his usual jeans and T-shirt for a traditional starched white cotton shalwar and black waistcoat and is standing in Narowal.

Out on the stump with Sharif, it is easy to see what Imran is up against. Flying between rallies in southern Punjab in a private jet that has previously flown Beyoncé and George Clooney and is stocked with yoghurt drinks and Perrier, Sharif is statesmanlike and quietly confident.

He admits Imran is his main rival in the cities though says in rural areas the contest is still with his old-time foes, the Pakistan People’s party of Benazir Bhutto and now headed by her widower Asif Zardari and son Bilawal. “Imran knows nothing except cricket,” he shrugs. “And he is abusive, too — he says he’ll beat me with a bat. That’s not nice.”

In stark contrast to the seat-of-the-pants feel of Imran’s campaign, everything around Sharif is highly organised. Security is tight — mobile phones are jammed. Before every stop he is given a folder with speaking points. But he has done this for years. “I love campaigning,” he says.

The former industrialist entered politics in the 1980s as a protégé of Pakistan’s military dictator General Zia ul-Haq but has been toughened by a period of jail and exile under General Pervez Musharraf.

He allows himself a smile when I ask how he feels about Musharraf being placed under house arrest after returning to Pakistan from London last month. “It’s exactly what he did to me,” he says.

On the campaign trail, he is helped by the record of his younger brother Shahbaz, long-time chief minister of Punjab. He can point at achievements such as improved schools, motorways, a new bus system and distribution of laptops to poor students even if they crashed whether users tried to remove the Sharif photograph on the start-up page.

“The youth is with us, not Imran,” he says. He proudly shows a picture of his daughter Maryam out campaigning.

Sharif’s last rally of the day is in the city of Multan. A huge charged-up crowd is waiting in a floodlit stadium where moths and bats circle the lights. He is greeted by a roar. Supporters kept 200 yards back behind a line of commandos wave green and white flags and stuffed tigers — his party’s symbol.

Sharif tells them he will end power cuts and slash government expenditure by 30%. They cheer every word. Afterwards, he is elated. “These people, lower and lower middle class, are the backbone of our party and we must work for them.”

Imran’s chance of success depends on voter turnout, which is historically very low, about 40%. “If he could take that above 50% and mobilise lots of new voters then we will surely see him getting lots of seats,” says Raza Rumi, a political analyst. Many might be deterred by violence though the army is to deploy 70,000 troops around polling stations.

Estimates give Imran at most 40 of the 272 seats, which would leave him as kingmaker, the two main parties needing his support for a coalition.

Imran insists he will do no such thing. “We’d rather sit in opposition,” he says. “We’re competing against these status quo politicians who brought us into this situation. There’s no way we’d work with them.”

First, though, Pakistan has to get through elections safely. The only time Imran loses his enthusiasm and looks down is when I ask what his two teenage sons back in London think about all this.

He told them the next time they saw him he would be prime minister. But in the meantime, he admits, the elder boy asked him to stop. “They are very anxious,” he says. “They are old enough to read the papers and see all the bombs.”

Pledge to halt US drones

Pakistan seems set for a collision course with America, with both leading candidates in Saturday’s elections vowing to demand the end of drone attacks in their territory.

“Drones are mostly killing innocent people,” Nawaz Sharif told The Sunday Times. “They are making the situation worse rather than better. If I am elected I will tell the Americans that clearly this is counterproductive, threatening our sovereignty and must stop.”

Asked how he would achieve this, given that drones do not fly from Pakistan territory, Sharif replied: “They want our co-operation on things, well we won’t do what they want.”

His views echo those of Imran Khan. Long an outspoken critic of drones, he has argued that they kill thousands of civilians and stoke resentment that creates more supporters for the Taliban.

If elected, Imran says he would also withdraw all Pakistan’s troops from the tribal areas that border Afghanistan, an act that would horrify Washington. The US has been trying to persuade Pakistan’s military to act against havens for militants in North Waziristan.

“We never had a problem with the tribal areas until General Musharraf sent troops in in 2004,” Imran said. “They are like a bull in a china shop and have taken us into a never-ending war.”

© Times Newspapers Ltd 2012

Registered office 3 Thomas More Square, London E98 1XY.

Registered in England No 894646

And it is in urban Punjab where Imran Khan‘s Pakistan Movement for Justice (PTI) party is eating into the lead of the frontrunner, Nawaz Sharif, head of the Pakistan Muslim League (PML-N).

And it is in urban Punjab where Imran Khan‘s Pakistan Movement for Justice (PTI) party is eating into the lead of the frontrunner, Nawaz Sharif, head of the Pakistan Muslim League (PML-N).

Imran Khan is standing as ‘a man of the people’ (Justin Sutcliffe)

Imran Khan is standing as ‘a man of the people’ (Justin Sutcliffe)

I hope they will find a way to make a more democratic way of life happen in their country.

It will be very interesting to watch how they meld these outcomes with their religion and the traditions of the area.

@Phil Perspective:

I bet there were people checking more than once – it’s surprising how fast you can forget or misremember something. (I’ve been voting at the same location for more than five years, and I still check the location every time.)