An unprecedented surge of criticism directed at Pakistan‘s chief justice by lawyers, politicians and even sections of a once-fawning media threatens to bring to a close years of interference in government affairs by the country’s top judges.

After he ordered the sacking of a sitting prime minister and the cancellation of host of critical economic initiatives, Iftikhar Chaudhry came to be regarded by many analysts as second only to the country’s army chief in his ability to influence the civilian government.

But as the 64-year-old edges towards retirement in December, a backlash has begun and increasingly his critics are speaking out.

“He’s a dictator! A judicial tyrant!” said Abid Saqi, the president of Lahore’s high court bar association, a powerful body representing 20,000 lawyers that in July called for the chief justice and two other judges to be charged with misconduct.

Saqi added: “He has destroyed the judiciary as an institution and destroyed the constitutions as a sacred document for his own personal aggrandisement.”

Until recently few dared to speak out at all, let alone use such colourful language. That was partly due to Chaudhry’s immense popularity – a 2011 Gallup poll found he was the most popular public figure in the country.

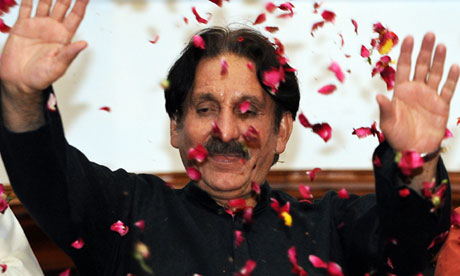

He became a key national figure during the struggle by the “lawyers’ movement” to force his reappointment in 2007 after he was sacked and put under house arrest by former military dictator Pervez Musharraf.

After returning to power on the back of one of the biggest popular movements the country has seen, Chaudhry burnished his reputation further by picking causes and hauling ministers and officials into his grand marble court building in Islamabad, where, in a holdover from the colonial era, judges are addressed as “my lord”.

It amounted to a judicial revolution. Or, as one critical lawyer puts it, “ripping up the entire supreme court jurisprudence that had gone before”.

“Iftikar Chaudhry has enjoyed a degree of power that is unparalleled,” said one lawyer. “He does whatever the hell he wants, he is outside the law and, most of the time, he is making it up as he goes along.”

He made extensive use of two once obscure legal tools: suo motupowers to investigate any issues of his choice, and contempt of court rules that bar the “scandalising” of the judiciary, which have been used to silence critics.

Suo motu, a Latin phrase meaning “of his own volition”, has become almost a household phrase in Pakistan, such is the chief justice’s enthusiasm for picking up populist causes highlighted by the media.

Some of its initiatives have won praise from human rights campaigners – particularly Chaudhry’s scrutiny of security agencies engaged in a dirty war against separatists in the province of Baluchistan.

He ordered individuals who have been “disappeared” without formal arrest to be produced before his court. And he was the architect of a major extension of rights to Pakistan’s transgender community.

But other actions have been much more controversial, particularly in the area of government contracts, privatisations and major infrastructure projects, which his court has cancelled or delayed on several occasions.

Critics say the court’s orders display an ignorance of economics and international business and have deterred badly needed investment, particularly in projects to help solve the country’s crippling energy shortages.

The court regularly involves itself in other matters of public policy, at various times ordering the almost insolvent government to slash prices of sugar, flour and gas. One of the few tax-raising initiatives in this year’s national budget had to be reversed after Chaudhry weighed in.

But it is his recent meddling in politics that has prompted attacks on him.

In July, he asked the country’s election commission to hold the presidential election a week earlier than planned, to which the main opposition party strongly objected but was not allowed to put its case.

It prompted intense anger within the political class over what was regarded as blatant violation of the independence of the election commission.

It also provided an opportunity for his enemies in the legal community – many bitter at what they claim is Chaudhry’s favouritism in appointing judges – to lash out.

Before this year’s general election in May, the previous government led by the Pakistan People’s party was reluctant to confront Chaudhry, even though it was continually subjected to his suo motu investigations.

In June last year, the party’s prime minister, Yousaf Raza Gilani, was forced to step down after Chaudhry found him guilty of contempt of court. The candidate proposed as his replacement was seen off by the supreme court even before he could be appointed while his ultimate successor was also threatened with being ousted.

“If we spoke out he was just calling everyone in contempt,” complained Chaudhry Manzoor Ahmed, a former PPP member of parliament. “The party was divided over whether to confront him because of fear that if we did so the whole system could be derailed.”

But fears that such standoffs could scupper Pakistan’s fragile transition to democracy have faded since the successful elections in May that ousted the PPP, which had been widely regarded as corrupt and worthy of Chaudhry’s investigations.

Chaudhry has also picked a fight with Imran Khan, the leading opposition politician whose Pakistan Tehreek-e-Insaf (PTI) bagged the second largest number of votes in May’s national elections.

He was accused of contempt after criticising the judiciary for failing to prevent alleged election rigging. The court ultimately backed down, however. If found guilty, a national icon with millions of diehard supporters could have been barred from elected office.

Babar Sattar, a lawyer who was recently reprimanded by the court for some of his newspaper columns, said the court had stepped up its efforts to quell mounting public criticism with contempt laws that are barely used in other parts of the world.

“The court is trying to control the narrative at a time when criticism is mounting, and to a certain extent it has succeeded,” he said, claiming newspapers are carefully vetting articles on the supreme court before they are published.

One person who could afford to throw caution to the wind was controversial billionaire property tycoon Malik Riaz Hussain, who last June launched a blistering assault on the chief justice.

He produced reams of documents detailing how Chaudhry’s son, a doctor-turned-businessman called Arsalan, had accepted gifts from him worth more than £2m in the form of stays in luxury London flats, hotels in Park Lane and gambling debts in Monte Carlo.

Riaz said he had been effectively bribed by Arsalan, who was trading on his father’s name for favours. Chaudhry responded, initially with a suo motu investigation that he led himself, before recusing himself from the case.

Although the investigation has since gone quiet, some suspect the many enemies Chaudhry has made in the legal profession and politics will try to get the issue revived after he steps down in December.

Most lawyers are anticipating calmer times under a new chief justice, with fewer challenges to the authority of government and parliament.

“The supreme court has evolved under Chaudhry into one of the country’s paramount institutions, and I don’t think that’s going to change,” said Sattar. “But criticism of this chief justice and his suo motureign has focused attention on some big problems and I think the next chief justice will want to address some of them.”