What ever Javed Latif said cannot and should not be defended – Period !

Our Announcements

Sorry, but you are looking for something that isn't here.

Posted by Rose in Leaders, Pakistani Modern Women Thinkers, Scholars, Soldiers, Women In Islam, Women Politicians on March 11th, 2017

Courtesy DAWN

Name-calling and fist fights are not uncommon when opposing politicians get together. But yesterday’s brawl between PTI lawmaker Murad Saeed and PML-N lawmaker Javed Latif underscored a disturbing trend.

During a press conference after an argument during a National Assembly session, Latif is reported to have passed distasteful remarks about Saeed’s sisters in connection with PTI Chairman Imran Khan.

His comments invited censure from all quarters, so much so that his name was soon trending on Twitter.

What ever Javed Latif said cannot and should not be defended – Period !

We just celebrated #womensday yesterday giving lectures on respect/rights and then we have MNAs like Jawed Latif sitting in our Parliament

However, this isn’t the first time women were disrespected at National Assembly.

Here’s a list.

According to veteran journalist Nusrat Javeed, Sheikh Rasheed was one of the first politicians to be observed passing derogatory remarks to his female peers.

“Benazir Bhutto was wearing a Pakistani green shirt and white shalwar. When she walked in, he quipped ‘You look like a veritable parrot’, which did not go down well with Ms. Bhutto at all and caused a ruckus in the house,” he recalled ina conversation with Dawn.

When Begum Zahid Khaleequzaman was minister for railways, Nusrat Javeed recalls her commenting on her workload thus: ‘I have so much work that I have one foot in Karachi and the other in Rawalpindi’.

“At this, someone from the backbenches had shouted ‘The people of Rahim Yar Khan must be enjoying themselves’.”

Before he infamously referred to PTI whip Shireen Mazari as a “tractor trolley” (more on that below), Defence Minister Khwaja Asif is reported to have called PML-Q’s Begum Mehnaz Rafi a “penguin” in reference to her limp.

At a National Assembly sessionin June 2016, Khawaja Asif was giving a speech on load shedding in Ramzan when PTI led by MNA Shireen’Mazari protested against some points he made.

Incensed by the interruption, Asif launched a tirade against Mazari, saying “Someone make this tractor trolley keep quiet.”

“Make her voice more feminine,” he said, according to eyewitnesses. Another lawmaker chimed in from the government benches to say “Keep quiet, aunty.”

Talk about not being able to handle criticism.

JUI-F Senator Hafiz Hamdullah hurled threats at analyst Marvi Sirmed during a TV talk show.

Although the threats were never televised, Sirmed revealed in a Facebook post that Hamdullah had swore at her and threatened to “take off her and her mother’s shalwar”. He also tried to beat her, she said in her Facebook post:

Although there was widespread condemnation for Hamdullah’s attack, he suffered no real consequences for it — a reality that allows for such abuse to occur in the first place.

When Shireen Mazari pressed State Minister for Parliamentary Affairs Sheikh Aftab on the security standards at the Islamabad airport, he said, “In airports abroad, they also strip-search you. Is that the international standard she wants,” he responded, to peals of approving laughter from the treasury benches.

The presence of vocal women with strong opinions tends to unsettle a lot of men, and from the six instances above, it’s apparent that our male politicians are no exception. The fact that some are repeat offenders show that their misdemeanours in Parliament are going unchecked. While they are occasionally censured, they suffer no real consequences for it — a reality that allows for such abuse to occur in the first place.

Asma Jahangir, a former president of the Supreme Court Bar Association and noted human rights activist, expressed similar views. She termed the Javed Latif episode a “shameful” one and called for appropriate action against the lawmakers concerned. “Once they are penalised, no one will dare talk in that tone,” she said while talking to a private television channel.

“It’s shameful that they don’t know how to talk to a woman. Are they the elected representatives of people attending an assembly session or some g

Posted by Sonia in Asif Haroon Raja (Retd):Pakistan Army, CURRENT EVENTS, Gujarat Massacre Narendra Modi Killers, Gujarat Massacres 2002, India -US Joint Export to Pakistan: Terrorism, India Backstabbing US, India Sponsored Taliban Terrorism in Pakistan, INDIA SPONSORED TERRORISM IN KARACHI, INDIA STATE SPONSORED TERRORISM IN PAKISTAN, INDIA TRAINED SUICIDE BOMBERS FROM AFGHANISTAN, India Training Suicide Bombers in FATA, INDIA'S ANTI-PAKISTAN TOXIC PROPAGANDA, INDIA'S CASTEISM, NARENDRA MODI -KILLER FOR PM INDIA, NARENDRA MODI INSPIRED MUSLIM GENOCIDE, NARENDRA MODI MASTERMIND MUSLIM GENOCIDE IN GUJARAT, OPINION LEADER on March 9th, 2017

Dr. Subhash Kapila has written an article in Eurasia Review the theme of which is, “Afghanistan cannot be abandoned to China-Pakistan-Russia Troika”. A highly melancholic and distressful picture has been painted by the writer in a bid to remind Donald Trump Administration that Afghanistan is slipping out of the hands of the US and unless urgent and immediate measures are taken to forestall the impending strategic loss, Afghanistan would be lost for good which will have grave consequences for the sole super power. A persuasive wake-up call has been given to inviting Trump to act before it is too late.

Subhash malevolently suggests that China-Pakistan axis now complemented by Russia will overturn the stability of the region. He has rung alarm bells that amidst the din of US Presidential election, Afghanistan has seemingly disappeared from the radar screen of USA and the Troika has fully exploited the vacuum to exploit it to its own advantage and to the disadvantage of Washington.

He sprinkles salt on the emotive feelings of USA by lamenting that the US huge investment and loss of lives of thousands of American soldiers have all gone waste owing to double dealing of Pakistan which the US has been claiming to be its strategic ally. He warned the new US policy makers that the Troika is fully poised to seize the strategic turf of Afghanistan and thus deprive the USA of its influence in Central Asia and Southwest Asia.

One may ask Subhash as to why no concern was shown by him or any Indian writer when the Troika of USA-India-Afghanistan assisted by UK and Israel was formed in 2002 to target Pakistan. The Troika that has caused excessive pain and anguish to Pakistan and its people is still active. All these years, Pakistan was maliciously maligned, ridiculed and discredited and mercilessly bled without any remorse. The objective of the Troika and its supporters was to create chaos and destabilize the whole region which was peaceful till 9/11.

The US installed puppet regimes of Hamid Karzai and Ashraf Ghani wholly under the perverse influence of India played a lead role in bleeding Pakistan by allowing so many hostile agencies to use Afghan soil for the accomplishment of their ominous designs.

The vilest sin of the so-called allies of Pakistan was its pretension of friendship and continuously stabbing Pakistan in the guise of friends. Worst was that Pakistan was distrusted and asked to do more against the terrorists funded, trained and equipped by the Troika and was humiliated by saying that it was either incompetent or an accomplice.

Driven by the desire to become the unchallenged policeman of the region and a bulwark against China, India assisted by its strategic allies has been constantly weaving webs of intrigue and subversion and striving hard to encircle and isolate Pakistan.

Proxy wars were ignited in FATA, Baluchistan, and Karachi to politically destabilize Pakistan, weaken its economy and pin down a sizeable size of Army within the three conflict zones so as to create conducive conditions for launching India’s much trumped up Cold Start Doctrine and destroy Pakistan’s armed forces.

India’s national security adviser has admitted that Pakistan has been subjected to his defensive-offensive doctrine to dislocate it through covert war. India’s Home Minister Rajnath Singh has vowed to break Pakistan into ten pieces. Modi has openly admitted that he has established direct links with anti-Pakistan elements in Baluchistan, Gilgit-Baltistan, and Azad Kashmir. He confessed India’s central role in creating Bangladesh in 1971 and has often stated that pain will be caused to Pakistan. This is done by way of acts of terror against innocent civilians including school children, resorting to unprovoked firing across the LoC in Kashmir, and resorting to water terrorism. Pakistan has been repeatedly warned to lay its hands off Kashmir or else lose Baluchistan.

Pakistan has miraculously survived the onslaughts of the Troika and has stunned the world by controlling foreign supported terrorism after recapturing 19 administrative units from the TTP and its allied groups and up sticking all the bases in the northwest, breaking the back of separatist movement in Baluchistan and restoring order in lawless Karachi by dismantling the militant infrastructure of MQM and banned groups. Army, Rangers and Frontier Corps assisted by air force have achieved this miracle of re-establishing writ of the State in all parts of the country. Eighty-five of terrorism has been controlled.

Random terror attacks are now wholly planned and executed from Kunar and Nangarhar in Afghanistan under the patronage of RAW ad NDS and supervised by CIA.

Consequent to the new wave of terrorism last month, Operation Rad-e-Fasaad has been launched as a follow-up of Operation Zarb-e-Azb to net facilitators, handlers, and financiers of terrorists and to demolish sleeping cells in urban centres. The scope of this operation has been extended to all parts of the country, and all the three services are taking part in it to cleanse Pakistan from the presence of paid mercenaries and fifth columnists.

Implementation of 20 points of National Action Plan is being religiously expedited to eliminate the scourge of terrorism. Afghan refugees are being returned and management of western border radically improved to prevent infiltration of terrorists.

Terrorism can however not be rooted out unless root causes that heighten extremism are addressed, and the bases in Afghanistan, as well as the patrons stoking terrorism, remain operative.

Pakistan has overcome energy crisis, considerably improved its macroeconomics and its stature in the world. Operationalization of CPEC, hosting of ECO meeting and holding of PSL cricket finals in Lahore have broken the myth of isolation.

Pakistan has made its defense impregnable by raising the level of minimum nuclear deterrence to full spectrum deterrence. Robust conventional and nuclear capability together with stable political and economic conditions have thwarted India’s desire to attack Pakistan overtly.

India and its strategic allies have been stopped in their tracks and left with no choice but to contend with covert war supplemented with propaganda war and coercive tactics to give vent to their pent-up anger.

India which is the chief villain of peace is deeply perturbed and is shedding tears over its failures and loss of billions spent on proxies to detach FATA, Baluchistan, Karachi and AJK from Pakistan, or to disable Pakistan’s nuclear program. The rapid progress made by CPEC has made the deadly Troika more rancorous.

Finding that its nasty game plan has run into snags with little chance of recovery, and above all Afghanistan is slithering away because of a resurgence of Taliban and ostensible insouciance of Washington, India is once again making efforts to provoke Trump and ruffle his feathers, the way it had efficaciously prevailed upon George Bush and Obama. It is now working on a new theme of demonizing so-called Troika of China-Russia-Pakistan, which is so far not in existence and is an illusion. Subhash is among the propaganda brigade selling this illusory theme and is suggesting that the so-called Troika have hegemonic and military designs against Afghanistan.

CPEC is an economic venture aimed at promoting peace and friend so–called Troika have hegemony in the region as a whole. It promises goodwill, harmony, and mutual prosperity through connectivity. Both China and Pakistan shun war mongering, proxy wars and psy operations to disparage others. The duo is bereft of colonial or quasi-colonial designs against any country. Since its memo is altogether different from the imperialist agenda of Indo-US-Israel, it threatens to unravel the global ambitions of the trio.

Whereas Afghanistan has not accepted the British demarcated Durand Line as a border with Pakistan and has been supportive of Pakhtunistan stunt, Pakistan has no disputes with Afghanistan and has always treated it as a brotherly Muslim neighbor.

Repeated invitations to India and Afghanistan to join CPEC and reap its benefits have been turned down. Both are complacent that CPEC will be a non-starter without an inclusion of peaceful Afghanistan, ignoring the fact that they are getting isolated. Moreover, a new route from Kazakhstan via Wakhan corridor is in pipeline which will bypass Afghanistan.

While China and Pakistan have jointly embarked upon the journey of peace and friendship and are attracting many countries, Russia is still hesitant and has so far not formally joined the bandwagon of CPEC which has great potential and has grandiose plans to link South Asia with Central Asia, Middle East, and Africa and eventually Europe.

Russia’s hesitation is owing to the fear of losing defence and economic markets in India. However, seeing the bright scope of CPEC and motivated by its age-old quest for warm waters, Russia will sooner than later abandon India because of Indo-US military agreements and gravitate towards CPEC. Recent developments have given a loud message to India that Russia is tilting towards Pakistan.

One of the reasons of Russia’s tilt is worsening security situation in Afghanistan which has turned into a big mess and is beyond the capacity of USA and Ghani regime to sort it out. Growing presence of Daesh in Afghanistan has alarmed Moscow since the declared objective of this branch of Daesh is to re-establish ancient Khorasan, which comprised of parts of Central Asia, Afghanistan, Iran, and Pakistan. The runaway TTP leaders Fazlullah, Khalid Omar and several others have tagged their names with Khorasani and have made Kunar-Nuristan as the base camp for the making of Khorasan.

Russia knows that CIA, Mossad, and RAW are secretly aligned with Daesh and are killing two birds with one stone. The threat of Daesh has impelled Russia to evince greater interest in Afghan affairs and there are reports that it is supplying arms to the Taliban to enable them to tackle the new threat. Some are saying, that Moscow might intervene in Afghanistan the way it had intervened in Syria on the pretext of grappling with Daesh.

If so, it might trigger a proxy war between the two big powers which will prolong the agony of people of Afghanistan as well as of Pakistan because of the spillover effect. This is exactly what India wants so as to retain its nuisance value in Afghanistan.

Will Trump get enticed and blindly jump into the same inferno from which Obama had extracted 1, 30,000 troops in December 2014 with great difficulty, and lose whatever prestige the US is left with by reinforcing failure?

Or else, he will stick to his policy of curtailing defence expenditure and pull out the 12000 strong Resolute Support Group and stop paying $8.1 billion annually to the corrupt regime in Kabul and inept Afghan security forces?

Or he takes a saner decision by making USA part of Russia-China-Pakistan grouping to arrive at a political settlement in Afghanistan and also opt to join CPEC and improve the economy of USA?

Making a realistic appraisal of the ground situation, the last option seems more viable and profitable for the USA, while the second option is dicey, and the first option will spell disaster.

The writer is retired Brig, a war veteran, defence analyst, columnist, author of five books, Vice Chairman Thinkers Forum Pakistan, DG Measac Research Centre and Member Executive Council Ex-Servicemen Society. Takes part in TV programs. asifharoonraja@gmail.com

Posted by Dr. Salman in Academic Charlatans on March 9th, 2017

Fair is employed at the Security Studies Program (SSP) within Georgetown University’s Edmund A. Walsh School of Foreign Service.[1][2]

Prior to this, Fair served as a senior political scientist with the RAND Corporation, a political officer with the UN Assistance Mission in Afghanistan and as a senior research associate with the United States Institute of Peace. She specializes in political and military affairs in South Asia.[3]

Fair has published several articles defending the use of drone strikes in Pakistan and has been critical of analyses by Human Rights Watch, Amnesty International, and other humanitarian organizations.[4]

Fair’s work and viewpoints have been the subject of prominent criticism.[5]Her pro-drone stance has been denounced and called “surprisingly weak” by Brookings Institution senior fellow Shadi Hamid.[5]JournalistGlenn Greenwalddismissed Fair’s arguments as “rank propaganda”, arguing there is “mountains of evidence” showing drones are counterproductive, pointing to mass civilian casualties and independent studies.[6] In 2010, Fair denied the notion that drones caused any civilian deaths, alleging Pakistani media reports were responsible for creating this perception.[7]Jeremy Scahillwrote that Fair’s statement was “simply false” and contradicted byNew America‘s detailed study on drone casualties.[7]Fair later said that casualties are caused by the UAVs, but maintains they are the most effective tool for fighting terrorism.[8]

Writing for The Atlantic, Conor Friedersdorfchallenged Fair’s co-authored narrative that the U.S. could legitimize support in Pakistan for its drone program using ‘education’ and ‘public diplomacy’; he called it an “example of interventionist hubris and naivete” built upon a flawed interpretation of public opinion data.[9]An article in the Middle East Research and Information Project called the work “some of the most propagandistic writing in support of PresidentBarack Obama’s targeted kill lists to date.”[10]It censured the view that Pakistanis needed to be informed by the U.S. what is “good for them” as fraught with imperialist condescension; or the assumption that the Urdu press was less informed than the English press – because the latter was sometimes less critical of the U.S.[10]

Fair’s journalistic sources have been questioned for their credibility[11]and she has been accused of having aconflict of interestdue to her past work with U.S. government think tanks, as well the CIA.[5] In 2011 and 2012, she received funding from the U.S. embassy in Islamabad to conduct a survey on public opinion concerning militancy. However, Fair states most of the grants went to a survey firm and that it had no influence on her research.[5] Pakistani media analysts have dismissed Fair’s views as hawkish rhetoric, riddled with factual inaccuracies, lack of objectivity, and being selectively biased.[11][12][13][14] She has also been rebuked for comments on social media perceived as provocative, such as suggesting burning down Pakistan’s embassy in Afghanistan or asking India to “squash Pakistan militarily, diplomatically, politically and economically.” She has been accused of double standards, partisanship towards India, and has been criticized for her contacts with dissident leaders from Balochistan, a link which they claim “raises serious questions if her interest in Pakistan is merely academic.“[13]

Fair has been accused of harassment of former colleague Asra Nomani, after Nomani wrote a column inThe Washington Post[15]explaining why she voted forDonald Trump in the 2016 United States Presidential Election. The harassment came in the form of Tweets taking aim at Nomani with a series of emotionally charged profanity and insults that lasted 31 consecutive days.[16]

The U.S. drone program creates more militants than it kills, according to the head of intelligence for the Joint Special Operations Command (JSOC), the U.S. military unit that oversees that very program.

“When you drop a bomb from a drone… you are going to cause more damage than you are going to cause good,” remarked Michael T. Flynn. The retired Army lieutenant general, who also served as the U.S. Central Command’s director of intelligence, says that “the more bombs we drop, that just… fuels the conflict.”

Not everyone accepts the assessment of the former JSOC intelligence chief, however. Still today, defenders of the U.S. drone program insist it does more good than harm. One scholar, Georgetown University professor Christine Fair, is particularly strident in her support.

In a debate on the Al Jazeera program UpFront in October, Fair butted heads with Pulitzer Prize-winning journalist Glenn Greenwald, a prominent critic of the U.S. drone program. Fair, notorious for her heated rhetoric, accused Greenwald of being a “liar” and insulted Al Jazeera several times, claiming the network does not appreciate “nuance” in the way she does. Greenwald, in turn, criticized Fair for hardly letting him get a word in; whenever he got a rare chance to speak, she would constantly interrupt him, leading host Mehdi Hasan to ask her to stop.

The lack of etiquette aside, Brookings Institution Senior Fellow Shadi Hamid remarked that Fair’s arguments in the debate were “surprisingly weak.”

After the debate, Fair took to Twitter to mud-sling. She expressed pride at not letting Greenwald speak, boasting she “shut that lying clown down.” “I AM a Rambo b**ch,” she proclaimed.

Fair alsocalledGreenwald a “pathological liar, a narcissist, [and] a fool.” She said she would like to put Greenwald and award-winning British journalist Mehdi Hasan in a Pakistani Taliban stronghold, presumably to be tortured, “then ask ’em about drones.”

Elsewhere on social media, Fair has made similarly provocative comments.In a Facebook post, Fair called Pakistan “an enemy” and said “We invaded the wrong dog-damned country,” implying the U.S. should have invaded Pakistan, not Afghanistan.

In another Facebook post, Fair insisted that “India needs to woman up and SQUASH Pakistan militarily, diplomatically, politically and economically.” Both India and Pakistan are nuclear states.

Fair proudly identifies as a staunch liberal and advocates for a belligerent foreign policy. She rails against neo-conservatives but chastises the Left for criticizing U.S. militarism. In 2012, she told a journalist on Twitter “Dude! I am still very much pro drones. Sorry. They are the least worst option. My bed of coals is set to 11.”

Despite the sporadic jejune Twitter tirade, Fair has established herself as one of the drone program’s most vociferous proponents. Fair is a specialist in South Asian politics, culture, and languages, with a Ph.D. from the University of Chicago. She has published extensively, in a wide variety of both scholarly and journalistic publications. If you see an article in a large publication defending the U.S. drone program in Pakistan, there is a good chance she wrote or co-authored it.

After her debate with Greenwald, Fair wrote an article for the Brookings Institution’s Lawfare blog. While making jabs at Greenwald, Hasan, and Al Jazeera; characterizing her participation in the debate as an “ignominious distinction”; and implying that The Intercept, the publication co-founded by Greenwald with other award-winning journalists, is a criminal venture, not a whistleblowing news outlet, Fair forcefully defended the drone program.

Secret government documents leaked to The Intercept by a whistleblower show that 90 percent of people killed in U.S. drone strikes in a five-month period in provinces on Afghanistan’s eastern border with Pakistan were not the intended targets. Fair accused The Intercept of “abusing” and selectively interpreting the government’s data. In a followup piece in the Huffington Post, she maintained that the findings of the Drone Papers do not apply to the drone program in Pakistan.

Greenwald pointed out that there are “mountains of evidence” showing that the U.S. drone program is killing large numbers of civilians, not just in Pakistan, but also in Yemen, Somalia, Afghanistan, and more. In these articles and the Al Jazeera debate, Fair took issue with the many studies cited by Greenwald, arguing they are flawed.

“Living Under Drones: Death, Injury, and Trauma to Civilians from U.S. Drone Practices in Pakistan,” an intensive 2012 study conducted over nine months by the law schools at New York University (NYU) and Stanford University, found that the U.S. drone program had killed hundreds of civilians in Pakistan, and “cause[d] considerable and under-accounted-for harm to the daily lives of ordinary civilians, beyond death and physical injury.”

The NYU/Stanford report was based on two investigations in Pakistan; hundreds of interviews with victims, witnesses, and experts; and a review of thousands of pages of government and media documents. It concluded that the U.S. drone program had “terrorize[d] men, women, and children, giving rise to anxiety and psychological trauma among civilian communities.” The study indicated that drones have even returned to target rescuers after drone attacks, making “both community members and humanitarian workers afraid or unwilling to assist injured victims.”

Fair accused the NYU/Stanford study of being “advocacy work,” arguing its findings were influenced by the human rights organizations Reprieve and the Foundation for Fundamental Rights. Reprieve has itself investigated the casualties of the drone program. It found that, in attempts to kill just 41 militants, the U.S. military killed 1,147 people in Pakistan and Yemen, as of November 2014.

According to Fair, Reprieve’s research is biased advocacy work, not scholarly research. She also accused the Bureau of Investigative Journalism (TBIJ), whose research the NYU/Stanford study cited, of being an advocacy organization.

For years, TBIJ has meticulously documented the casualties of drone strikes in Pakistan, Yemen, Somalia, and Afghanistan. It estimates between 423 and 965 Pakistani civilians have been killed by the U.S. drone program. TBIJ has also documented how U.S. drones have targeted rescuers, and even attacked funerals of people killed in drone strikes.

I reached out to the Bureau and, although it did not want to comment on the affair, it maintained it is a journalism organization, not an advocacy group. TBIJ pointed out it has done work not just on drones, but also on political corruption in Europe, British political party funding, deaths in police custody in the U.K., and more.

Numerous other studies have found the U.S. drone program in Pakistan to be wildly unpopular and counterproductive. A 2012 poll conducted by leading polling agency Pew found that just 17 percent of Pakistanis supported the U.S. drone program. In an article in The Atlantic, Fair and colleagues argued this Pew report was flawed. The day after the piece was published, The Atlantic’s own Conor Friedersdorf called Fair out on her sloppy methodology, accusing her of making “strained interpretations of public opinion data.” “I don’t know that I’ve ever seen a better example of interventionist hubris and naivete,” Friedersdorf observed.

In the time since Fair criticized Pew’s original survey, the polling agency has done more. A 2014 Pew poll found that 66 percent of Pakistanis opposed the U.S. drone program. And another 2014 Pew study found that 67 percent of Pakistanis agreed that U.S. drone strikes “kill too many innocent people.” Only 21% of participants said drone strikes “are necessary to defend.”

In 2010, Fair boldly claimed that U.S. “drones are not killing innocent civilians,” wholly writing off all reports of civilian casualties. Fair rejected the research done by David Kilcullen, a former counterinsurgency adviser to Gen. David Petraeus, and Andrew Exum, a fellow at the Center for a New American Security, that said otherwise.

At the time Fair insisted that civilians had not been killed, an investigation conducted by Peter Bergen and Katherine Tiedemann of the New America Foundation had found that the total of civilian deaths from U.S. drone strikes from 2006 to mid-2010 was “in the range of 250 to 320, or between 31 and 33 percent.”

Since then, Fair has conceded that civilians have been killed in the U.S. drone program, but she avers that their deaths are, although unfortunate, justified in the fight against extremism in Pakistan. She rebukes any study that suggests the drone program in Pakistan makes things worse or even is unpopular.

In its research, Amnesty International came to the conclusions most scholars and journalists have. Amnesty’s Pakistan researcher Mustafa Qadri explained in 2012 that, because of the drone program, “when we researched these cases, we found people were fearful of the U.S. the way they’re fearful of the Taliban.” Qadri continued, noting Pakistanis “have told us they’re taking sleeping tablets at night. They don’t know when they’re going to be targeted if they’ll be targeted, why they’ll be targeted. That really is a shocking situation.”

Fair herself admitted in her article in Lawfare that, in general, the scholarship around the U.S. drone program in Pakistan “produces mixed results, with some work showing the efficacy of leadership decapitation while other studies find that it is sometimes effective or even counterproductive.”

Pakistani-American scholar Hassan Abbas joins a long list of experts who have argued that the U.S. drone program creates more militants than it kills.

The U.N., Amnesty International, and Human Rights Watch have even said the Obama administration may be guilty of war crimes for its drone program. Renowned public intellectual Noam Chomsky, similarly, has characterized the U.S. government’s extrajudicial assassination of militants via drone as a massive and illegal campaign of global terrorism.

Fair’s response to most critics is to accuse them of either not being specialists (e.g., Malala Yousafzai, the Nobel Prize-winning Pakistani teenager who has strongly criticized the U.S. drone program and warned President Obama it was fueling terrorism) or to claim they lack adequate data to justify their point.

After hearing Fair’s rejection of the preponderance of studies on the U.S. drone program in Pakistan, Faiza Patel, co-director of the Brennan Center’s Liberty and National Security Program at New York University School of Law, asked how Fair can “claim to be the only person who knows what Pakistanis think of drones.”

Fair says few researchers have been to Federally Administered Tribal Areas (FATA) in northwestern Pakistan, where most U.S. drone strikes take place. She argues, therefore, that they cannot know what Pakistanis there think.

I reached out to sociologist Muhammad Idrees Ahmad, who is from Pakistan’s northwestern frontier region, near FATA, and has been researching the drone war for the past decade. Ahmad teaches at the University of Stirling and has written for years about the U.S. drone program. He is also the author ofThe Road to Iraq: The Making of a Neoconservative War.

“Fair claimed that opposition to drones was a luxury indulged in by elites living in Lahore or Islamabad. In FATA, she said, drones were popular. As a matter of fact, it’s only among the elites of Islamabad and Lahore that one usually finds Pakistan’s few drone defenders,” Ahmad said. “In FATA, outside a small Shia enclave, there is little support for drones.”

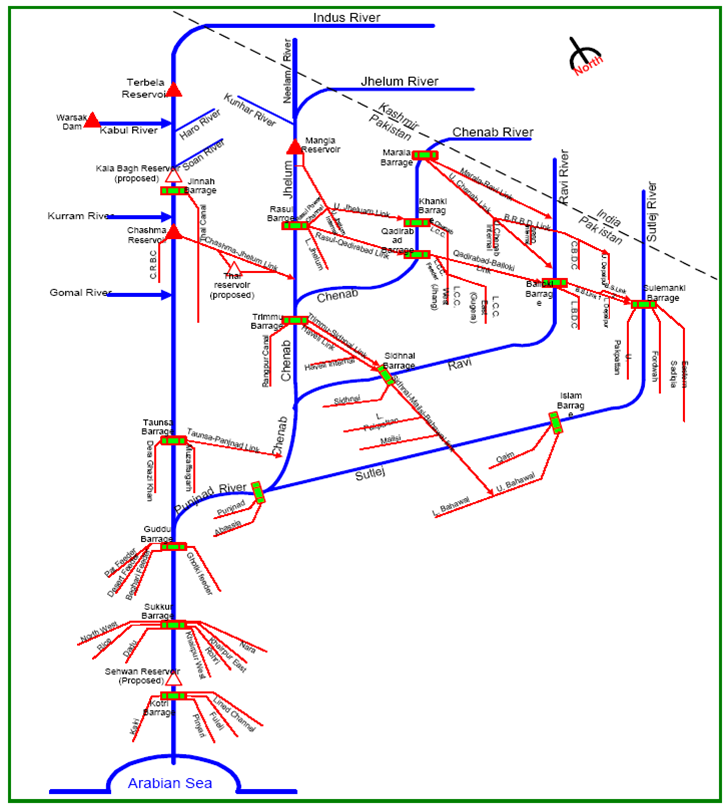

Posted by Sajjadgul in India's River Water Hegemony on March 7th, 2017

Pakistan is facing acute shortage of water, as being on lower riparian in connection with the rivers emanating from the Indian-Occupied Kashmir. Since its inception, India has never missed an opportunity to victimize Pakistan by creating deliberate water scarcity with the aim to damage the latter agriculturally.

Historically, India has been trying to establish her hegemony in the region by controlling water sources and damaging agricultural economies of her neighbouring states. New Delhi has water disputes with Pakistan, Nepal, and Bangladesh. Indian extremist Prime Minister Narendra Modi who has given the concerned departments to continue construction of dams has ordered diverting water of Chenab River to Beas, which is a serious violation of the Indus Water Treaty (IWT) of 1960. Therefore Pak-India water issue has accelerated.

Taking cognizance of India’s diplomacy against Pakistan, a seminar on the subject “Hydro-Politics around Pakistan: Reassessing: The Efficacy of Indus Water Treaty (IWT)” was organized by the National Defence University (NDU), Islamabad on January 17, 2017. Gen. Rizwan Akhtar (Former DG ISI), the President NDU, including other experts on the subject highlighted the significance of IWT and the need for deliberations on the subject to find out a viable solution to the problem.

Gen Muzammil Hussain (R), (Chairman WAPDA) said that the subject of IWT is very important for the country. He, however, was unhappy to find out that not a single representative had come from Ministry of Foreign Affairs and even from WAPDA to attend this important seminar. Dr. Zaigham Habib, while talking on “Hydro-Hegemony in South Asia and Implications for Pakistan” regarded India as a Hydro-Hegemon stated, “neighbours view India with suspicion; it is difficult to conduct a discussion on common-interest issues with her in good faith. India’s insistence on secrecy about hydrological data contributes to the distrust within the region. Timely and adequate information is never fully given to Pakistan, Bangladesh, and others on water data and on National River Linking Projects.”

Mirza Asif Baig, Pakistan’s Commissioner for Indus Waters, dilated on the “Efficacy of The Indus Waters Treaty”. He mostly talked on the technicalities of the treaty and did not show any concern about the violations of the treaty already being carried out by India.

Suleman Najib Khan regarded Indus Waters Treaty signed at Karachi a seriously flawed treaty, which did not serve Pakistan’s interests. He was very critical of the role and efficacy of Indus Water Commission. He was of the view that all the chairmen’s have failed to guard the interests of Pakistan, they neither have the expertise nor the will to contribute positively. He highlighted the urgent need of making reservoirs on River Indus, including Kala Bagh Dam (KBD), to save the country from starvation in the near future. He, however, was opposed to Bhasha dam on purely technical grounds. He informed the audience that Kabul River contributes around 20-25 % to Indus River water, especially in winters. India is pursuing Afghanistan to build multiple dams on Kabul River which would further deprive Pakistan of much-needed water. He was of the view that Pakistan should also get into some treaty with Afghanistan regarding the continuous flow of River Kabul water. He further stated that propaganda against KBD was deliberately launched to create conviction in the locals that the natural drainages of Peshawar & Kohat valleys, which will be blocked as a result of back pressure from the KBD reservoir. Similarly, propaganda was also launched that the KBD reservoir will create water logging in Mardan, Charsada, Swabi, Pabbi, and Nowshera, despite all of them being higher than 915 feet from sea level. In Sindh, the propaganda was launched that KBD would restrict water supply to Sindh resulting into vanishing of Mangroves and intrusion of sea water. As a matter of fact, Sindh uses five times more irrigation water than Punjab. Flood irrigation on a 14 km wide strip keeps both the Pirs and Waderas happy and prosperous that’s why they do not want this water to be regulated.

Ahmer Bilal Soofi, Advocate Supreme Court, President Research Society of International Law, Former Federal Minister for Law, Justice and Parliamentary Affairs and President WWF Pakistan spoke on “IWT and International Law: Options for Pakistan”. The main points of his discourse were as follows:-

The IWT cannot be unilaterally terminated, according to Article 12 (4) of IWT; only a new treaty drafted and mutually ratified by both India and Pakistan can only replace existing treaty.

There is no provision which expressly authorizes India to construct a certain number of dams. Neither is there one which prohibits India from making dams beyond a certain number. Clearly, therefore, the number of dams that India wishes to construct on the Western Rivers is an issue outside the scope of the treaty.

IWC does not possess lawyers to contest its case at international level. He suggested that IWC must have a pool of good and qualified lawyers, specialized in international laws. He even offered to pay the salaries of such lawyers for a year, to start with.

Pakistan is the signatory of Paris Agreement, which demands to move away from fossil fuel based energy generation and shifting from non-renewable to renewable sources of energy ie going for Hydro-electric Power Generation. This agreement can also be utilized for strengthening our case for resolving water disputes with India.

Shams Ul Mulk, former Chairman WAPDA, was of the view that Pakistan’s hydel policies have throughout been formulated by our enemy’s agents. India has succeeded in placing their agent’s at all important places of decision making in this sector. Various military and civilian rulers have also been tricked by these agents in getting decisions which, in the long term, have proved detrimental for the country. About IWT, India has been violating the treaty throughout and keeping Pakistan in the dark about various projects which she has been making on western rivers. He also indicated the need and urgency of building more water reservoirs including Bhasha and Kalabagh Dams. He very strongly recommended the revival WAPDA with all power generation and distribution companies/agencies, working under it.

Nevertheless, more dams/reservoirs on Indus River be made, including KBD, at priority basis. The government must create consensus among all the provinces and thwart any negative propaganda by our enemies in this regard. And the violations of IWT by India be contested through aggressive diplomatic maneuver, legally, internationally. Otherwise, India will continue victimizing Pakistan by creating water shortage.

Additional Readings

Copyright © www.www.examrace.com

Location of Indus River India and Pakistan water-distribution treaty, brokered by the World Bank (then the International Bank for Reconstruction and Development). Deals with sharing of water of six rivers — Beas, Ravi, Sutlej, Indus, Chenab and Jhelum between the two countries Signed in Karachi on September 19, 1960 by then Prime Minister Jawaharlal Nehru and President of Pakistan Ayub Khan. Ravi, Beas and Sutlej eastern rivers came under the control of India and Indus, Jhelum and Chenab the western rivers went under the control of Pakistan. India can only use 20% of the water of Indus River. Indus flows through India first. Most disputes were started by legal procedures, provided for within the framework of the treaty. The treaty has survived India-Pakistan wars of 1965, 1971, and the 1999 Kargil standoff as well Kashmir insurgency since 1990. It is the most successful water treaty in the world.

Read more at: https://www.examrace.com/Current-Affairs/NEWS-India-Suspend-Talks-on-Indus-Waters-Treaty-Important.htm

Copyright © www.www.examrace.com