Our Announcements

Sorry, but you are looking for something that isn't here.

Posted by Fawad Mir in China-Pakistan Friendship & Brotherhood on March 8th, 2013

Pakistan, China joint military exercise YOUYI-IV in mid November

‘Pakistan Times’ Federal Bureau

RAWALPINDI: Pakistan, China Joint Military Exercise YOUYI-IV is scheduled to be held in mid November in Pakistan.

RAWALPINDI: Pakistan, China Joint Military Exercise YOUYI-IV is scheduled to be held in mid November in Pakistan.

The joint exercise, spread over a period of two weeks, is aimed at mutual exchange of experience and information through a comprehensive training programme in real time, a press release issued by ISPR said here on Thursday.

The exercise will encompass techniques and procedures involved in Low Intensity Conflict Operations (LIC) environment. This joint interaction in form of military exercise aims at sharing and enhancing expertise of both armies in countering terrorism.

Exercise YOUYI which literally translates ‘FRIENDSHIP’ between the two countries started in 2004. Pakistan Army was the first foreign army to conduct any exercise on Chinese soil. So far three exercises have been conducted; including two in China and one in Pakistan. These exercises were mandated to boost existing professional relationship between the two friendly Armies.

It may be mentioned here that Pakistan and China enjoy extremely close and brotherly relations since their inception, which have matured and strengthened over the years. The forthcoming Joint Military Exercise YOUYI-IV will certainly pave the way for further cementing the existing bilateral relations between Pakistan and China.

Chinese navy to join Pakistan exercise

The 14th Chinese naval squad heading for Somali waters will take part in a multi-national exercise in Pakistan in March, military sources said Sunday.

The “Exercise Aman-13″ is scheduled to start in the North Arabian Sea March 4. Aman is an Urdu word meaning “peace”.The fleet, sent by the Chinese People’s Liberation Army (PLA) Navy, departed Saturday from a port in Qingdao of east China’s Shandong province to the Gulf of Aden and Somali waters for escort missions.

The 14th convoy fleet comprises three ships — the missile destroyer Harbin, the frigate Mianyang and the supply ship Weishanhu — carrying two helicopters and a 730-strong troop, all from the North China Sea Fleet under the PLA Navy.Since December 2008, authorized by the UN, the Chinese navy has organised 14 fleets to the waters of the Gulf of Aden and Somali waters to escort 5,046 Chinese and foreign ships.More than 50 Chinese and foreign ships have been rescued or assisted during the missions. – KahleejNews

|

The Turkish and Pakistani military forces have initiated two joint military exercises, a naval operations exercise and an air force cooperation drill, beginning on Monday Today`s Zaman reported.

According to a statement released by the General Staff, the combined naval military exercise code-named “Aman-2013,” being held at the invitation of the Pakistani naval forces, will be conducted from March 4 to 8 in the Indian Ocean. The aim of the exercise is “to show a common determination against terrorist and criminal events in a naval operating area” and “to contribute to international peace and stability,” as it was described in the official statement.

|

Turkey will participate in the naval exercise with the frigate TCG Gokova (F-496), one underwater defense and one underwater assault team and two staff officers. Various units from Australia, Bangladesh, China, England, Indonesia, Italy, Japan, Malaysia, Sri Lanka, the United Arab Emirates (UAE) and the United States will also participate, according to the General Staff statement.

Five Turkish F-16 fighter jets will join the air force exercise. A previous Indus Viper operation took place at the Mushaf Air Base in 2008.

Posted by admin in Roshan Pakistan on March 7th, 2013

The shifting landscape has made the country a hot favourite for the international media.

The shifting landscape has made the country a hot favourite for the international media, with the number of foreign correspondents coming to the country more than doubling in the past decade. According to the Press Information Department, the number of residing-journalists has risen from approximately 130 in 2001 to 250 in 2012 while the number of visiting journalists has risen from 30-40 to nearly 400 as of today. Along with sending reporters to the country, a number of foreign publications also hire local reporters to report news from Pakistan.

Source: Press Information Department, Pakistan

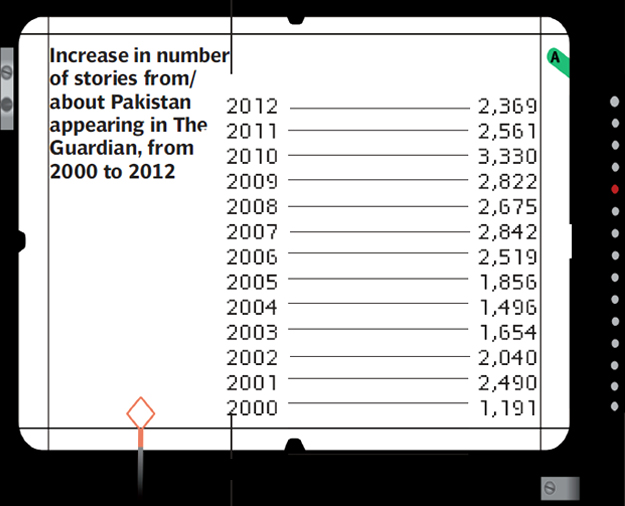

Stories from Pakistan also began to occupy a significant space in most international publications. For example, a search on The Guardian’s website for stories from/about Pakistan shows an increase from 1,191 stories in 2000 to 2,369 stories in 2012.

Source: Press Information Department, Pakistan

A closer look at the nature of the stories reveals that the largest number of stories about Pakistan appeared in the ‘World News’ section, featuring hard news events like terrorist attacks, political developments and international relations while the smallest number of stories appeared in the ‘Law’ section of various international newspapers. The ‘Travel’, ‘Lifestyle’, and other sections featuring soft-stories also contained disproportionately fewer stories.

Source:http://www.guardian.co.uk/search?q=Pakistan+&date=date%2F2012

____________________________________________________________

Watch related videos on Vimeo here:

• Foreign correspondents in Pakistan – Part I

• Foreign correspondents in Pakistan – Part II

• Foreign correspondents in Pakistan – Part III

• Foreign correspondents in Pakistan – Part IV

• Foreign correspondents in Pakistan – Part V

____________________________________________________________

While the coverage of sensitive issues by the foreign media has been applauded for being thorough, credible, and accurate, the range of stories has often been criticised for being too narrow and showing a skewed picture.

“The foreign media writes about issues that people want to read. Some of us might not like what they write, but what they write about the country is fairly realistic and accurate,” says journalist Najam Sethi.

According to Taha Siddiqui, an Islamabad-based journalist reporting for foreign news outlets, such stories are preferred by international editors and tend to get more coverage because they are relevant to the global audience. Given that Pakistan is a nuclear-armed ally in the war on terror, located next to Afghanistan, the country’s stability is a key concern for everyone.

“It’s not actually a bias towards certain stories, but the baggage that comes with the country’s reality,” elaborated Sethi.

Cyril Almeida, assistant editor at Dawn.com, feels that there is not much difference between stories from Pakistan that make headlines in the local media, versus those in the international media. However, he points out that in the case of international publications, not only are stories met with constraints of space and time, but are also competing with stories from across the world. Therefore, a story has to be truly “violent, newsworthy or uplifting” to actually make it to the news pages.

“We should be more concerned about the product [Pakistan], rather than its image. We should fix the product rather than obsess about its image,” he said.

In comparison, Almeida stated that a country like India gets much more coverage by virtue of its size, economic strength and tourist attractions, whereas in comparison there aren’t many feel-good stories to write about in Pakistan these days.

On the other hand, Press Trust of India correspondent Rezaul Hassan, feels that it is not a lack of reporting but certain trends that the international media tends to highlight. He cites the portrayal of fashion shows as a combat mechanism against terrorism in Pakistan as one of the examples of a story that most foreign organisations focused on a couple of years ago.

“But Pakistan is so much more. It is also a country transitioning towards a democratic rule. It is a country where the president has completed his tenure despite all odds. So many young people are determined to make something out of this country despite the problems with the economy and extremism and more needs to be written about all this,” he said.

National Public Radio host and author of “Instant City: Life and Death in Karachi”, Steve Inskeep agrees that the international coverage of the country, while often very good, is too narrow. He states that nearly all of the stories revolve around bombers and the Taliban and the ISI. While those stories are vital, Pakistan has a lot more to offer.

“I do not think that a broader picture of Pakistan would always be more ‘positive’. There are many problems, and many kinds of violence, tremendous poverty, inequality and problems of sustainability and democratic survival. But the picture can be fuller, more interesting and truer,” he said.

However, for foreign reporters, looking for a ‘bigger and broader picture of the country’, and the tedious process of reporting required by such a ‘big picture’, can be particularly challenging due to language barriers, security concerns and complex political and social realities of the country.

While being on the ground is important for journalists, most of them rely on stringers, fixers and interpreters for access to stories in areas like the Federally Administered Tribal Areas. Additionally, stringers can also play an important role in gaining access to sources and help acquire a more accurate understanding of the country’s customs, language and history.

According to Richard Leiby, bureau chief for The Washington Post, the qualities intrinsic to a good stringer are being good-natured, flexible and well-connected.

“Sometimes even a driver can open a window into the local culture and influence a story,” says Inskeep. He narrates his experience of watching cricket over dinner with his driver’s family, which helped him understand the rules and the local fascination with the sport – which gave him a fresh angle from which to view the story.

Language barriers

Lack of knowledge of Urdu and other local languages can often create difficulties in communicating with sources. Stringers and translators can be particularly helpful in such situations.

According to Inskeep, the only solution was to ask questions, and keep asking them till you were clear about an issue.

“While some people seemed suspicious and did not say all they knew, others were delighted to share their stories. No matter where you are in the world, if you are willing to listen, you hear the most amazing things,” he said.

Hassan recalls how people initially assumed his Urdu/Hindi skills to be perfect, since he belonged to India. This was far from the truth back then. But now, he claims that he can speak these languages as well as the locals.

He describes his term in Pakistan as one of the most “fertile periods” of his professional life but the journey has not been equally satisfying in personal terms. Restrictions on travel frustrate him the most.

Being one of the only two Indian journalists working in Pakistan currently, he has often encountered great trouble while getting visa extensions.

“There are times when I have been without a visa for up to six months,” he said, adding that it was unfortunate that such hindrances existed on both sides of the border.

“We try and look for stories that are different from ‘the story’ that everyone else is writing about,” says Michele Leiby, also a correspondent for The Washington Post.

But that is not always easy given the restrictions on foreign correspondents when it comes to travelling freely outside Islamabad and Punjab. Huge amounts of paperwork is required for such travels, which consumes a lot of time, often at the cost of dropping a story.

While talking to the average Pakistani, or getting really close to a story might be challenging for foreign reporters due to security reasons and language barriers, access to important government, military and bureaucratic officials is often easier.

“Pakistani political leaders and officials are sensitive, I think, about the image their country presents to the world, so they tend not to totally ignore calls,” says Leiby.

Hassan, who has faced unusual difficulties in getting information from the government, shares a completely different opinion. “There are people who flatly refuse to talk to you, or even share the more harmless kind of information, simply because you are Indian,” he said.

Reporting for a foreign publication also allows for a certain level of freedom and fearlessness in stories – a rare luxury for local reporters. While local journalists might have better access, the deteriorating security situation for journalists in the country prevents them from actually covering those stories, elaborates Rob Crilly, the Pakistan correspondent for The Telegraph. He cites stories on Balochistan, blasphemy, religion and the workings of ISI as some of the dark corners upon which foreign reporters can tread relatively freely.

“We work here as if we were working in the United States. We are not under risk of being abducted, jailed or censored. The worst that can happen to us for doing these stories is that we will get kicked out,” says Leiby in agreement.

The threat to journalists in Pakistan applies more to local reporters rather than to us and I have immense respect for men and women here who continue to do their job despite such difficulties, added Mrs Leiby.

Covering Pakistan: the experience

“Spend two weeks in Pakistan: you are confused. Spend one year in Pakistan: you are more confused,” says Leiby, who has been in the country for the past one year along with his wife.

He added that the cultural adjustments would “blow your mind away”, if one did not have any previous experience of working in the Muslim world. For Leiby however, the adjustment was not so drastic due to his previous assignments in Gaza, Iraq and Egypt.

“My major perception adjustment was to the idea that everyone would hate me as an American. That is indeed far from the truth,” he explains how some of his pre-conceived myths were dispelled upon arrival.

There were exceptions like the time he stepped out to the nearby petrol station to get a few quotes for a story where someone inquired what branch of the Central Intelligence Agency he belonged to. When he responded, “No sir, I work for the Washington Post,” the man retorted: “Isn’t that the same thing?” Leiby recalls with a laugh. Such incidents however, are an exception rather than the norm, he added.

But the suspicion towards British reporters is lesser, which makes the job relatively easier for them, as compared to an American reporter or one from any other European country, says Crilly. Having worked here for the past two and a half years now, he recalls the transition as a “relatively easy one”.

“You can say a lot of bad things about the British Empire but one of the things it has done is give us a common language, a mutual love for cricket and a cup of tea. That has opened doors for me in many ways,” he said.

For an Indian journalist, covering Pakistan is “a dream job”, says Hassan who has been doing so for the past five years. For him the choice of working here was extremely straightforward as the country figures prominently in Indian politics and diplomacy and people back home love reading about it. However, there was much warning from fellow countrymen for these journalists before they came to Pakistan about the unstable security conditions and people from agencies following him around.

On their first night in Pakistan, Hassan and his wife returned to their hotel safely late at night. Despite all they had heard, the couple decided to go out and discover for themselves. “Such small things highlight the difference between perceptions and reality,” he said.

For Michele Leiby, the surprise came at the sight of armed men and the abundance of weapons everywhere.

“Initially, I was surprised to see even the guard outside a Nando’s (a foreign food chain) outlet holding a gun. But with time, you get used to these things,” she added with a smile.

Her husband recalls the first sound of gunshots he heard in the country, which were later discovered, to his amusement, to be part of a wedding celebration around the street corner.

A hospitable people

The warmth and generosity of the Pakistani people struck a chord with all foreign correspondents. “Wherever you go, there is a cup of tea, often accompanied by an invitation to lunch. The hospitality still overwhelms me,” says Crilly.

Michele Leiby also feels that she has learnt the true meaning of warmth and hospitality through the people in Pakistan. She fondly recalls a family in the refugee camps in Jalozai, who opened their hearts and homes to them despite having nothing aside from their tent, a cot, and a few pigeons.

Despite the warnings and potential bumps and dead ends, the ride for a foreign journalist reporting in Pakistan is an exhilarating one. “You come to Pakistan, it feels like you are driving at 80 miles/hr every day. When you go back home, you go back to driving at 20 miles/hr. It is such an incredible rush being here”, says Hassan.

Strange tales from Pakistan

Pakistan Loving Fatburger as Fast Food Boom Ignores Drones – Published in January 2013 byBloomberg, this article traces the growth of American franchises and increase in consumer spending in Pakistan over the past few years. However, the headline and the parallels drawn between enjoying food at American chains and terrorism drew a large amount of criticism, especially over social media

Bin Laden City Abbottabad to build amusement park: Published in AFP on February 2013,the story is about the government plans to build an amusement park in the city of Abbottabad. However, the reference to Abbottabad as “Bin Laden City”, has been criticised for limiting the city’s history and identity to the final refuge of a terrorist.

In Pakistan, underground parties push the boundaries – Published in August 2012 byReuters, this report juxtaposes the culture of partying, drinking and dancing by young people against a backdrop of rising extremism and Talibanization in Pakistan. It received a lot of criticism for misquoting sources and drawing parallels between two exaggerated extremes in the country.

Designers shrug off militant violence for Pakistan’s fashion week: A series of stories ran in 2009 in several foreign newspapers, covering Pakistani fashion weeks and portraying it as an alternative mechanism for combating the increasing extremism in the country. This kind of coverage received criticism for juxtaposing two different extremes with each other.

Stories covered exceptionally well by foreign media

1. Osama bin Laden’s death: How it happened: The level of detail, precision and openness in the reporting on the bin-Laden operation by the foreign publications remains unmatched by local newspapers. The shortcomings of the ISI and the Pakistani army have also been addressed openly, a subject that remains sensitive for local papers.

2.Karachi:Pakistan’s bleeding heart: A detailed story on the violence in Karachi, incorporating perspectives from the various stakeholders and mapping out the various sectarian and political clashes in the city.

3. Pakistan’s secret dirty war: The piece sheds light on the conflict in Balochistan, the issues of missing persons and the insurgency in the area. The reporting in the story was extremely detailed and highlighted an important issue in the country, mainly ignored by mainstream media at the time.

4. Cheating spouses keep Pakistani private detectives busy: An unusual and different story detailing the woes of women in Pakistan, who hire detectives to keep track of their spouse’s whereabouts and activities. The story breaks free of the usual pattern of terrorism and bombs and chronicles the dilemmas of an average Pakistani.

5. In Pakistan’s Taliban territory, education is a casualty of conflict: A profile of a school in Waziristan which continues to function despite all odds, the story offers a unique perspective into the area, unlike the usual tales of bombs and destruction that emanate from the region.

(WITH ADDITIONAL INPUT FROM VAQAS ASGHAR, WAQAS NAEEM AND FARMAN ALI)

Published in The Express Tribune, February 24th, 2013.

Posted by admin in "Jihadi" Outfits of Terrorism, Afghan -Taliban-India Axis, Foreign Policy, Hypocrites in Islam, India, Jahiliya "Jihadis"Illiterate Fanatics, MUSLIMS, OUTRAGE AGAINST MUSLIM GENOCIDE, Pakistan Fights Terrorism, Pakistan's Fights Terrorism, SHIA +SUNNI = MUSLIMS=ISLAM=PEACE on February 23rd, 2013

Saudi & Iranian should take their battles elsewhere, Pakistan is not up for sale as a battleground for the destruction of Shia-Sunni Unity. The blood of 1,200 Pakistanis Shias of Hazarawal ethnicity is on the hands of Saudi sponsored proxies, the Lashkar-i-Jhangvi. They are a creation of Saudi money

Iran soon rattled its own sabers. Iranian parliamentarian Ruhollah Hosseinian urged the Islamic Republic to put its military forces on high alert, reported the website for Press TV, the state-run English-language news agency. “I believe that the Iranian government should not be reluctant to prepare the country’s military forces at a time that Saudi Arabia has dispatched its troops to Bahrain,” he was quoted as saying.

The intensified wrangling across the Persian—or, as the Saudis insist, the Arabian—Gulf has strained relations between the U.S. and important Arab allies, helped to push oil prices into triple digits and tempered U.S. support for some of the popular democracy movements in the Arab world. Indeed, the first casualty of the Gulf showdown has been two of the liveliest democracy movements in countries right on the fault line, Bahrain and the turbulent frontier state of Yemen.

Saudi Arabia’s flag

Source: Military Balance

But many worry that the toll could wind up much worse if tensions continue to ratchet upward. They see a heightened possibility of actual military conflict in the Gulf, where one-fifth of the world’s oil supplies traverse the shipping lanes between Saudi Arabia and Iran. Growing hostility between the two countries could make it more difficult for the U.S. to exit smoothly from Iraq this year, as planned. And, perhaps most dire, it could exacerbate what many fear is a looming nuclear arms race in the region.

Iran has long pursued a nuclear program that it insists is solely for the peaceful purpose of generating power, but which the U.S. and Saudi Arabia believe is really aimed at producing a nuclear weapon. At a recent security conference, Prince Turki al Faisal, a former head of the Saudi intelligence service and ambassador to the U.K. and the U.S., pointedly suggested that if Iran were to develop a weapon, Saudi Arabia might well feel pressure to develop one of its own.

The Saudis currently rely on the U.S. nuclear umbrella and on antimissile defense systems deployed throughout the Persian Gulf region. The defense systems are intended to intercept Iranian ballistic missiles that could be used to deliver nuclear warheads. Yet even Saudis who virulently hate Iran have a hard time believing that the Islamic Republic would launch a nuclear attack against the birthplace of their prophet and their religion. The Iranian leadership says it has renounced the use of nuclear weapons.

How a string of hopeful popular protests has brought about a showdown of regional superpowers is a tale as convoluted as the alliances and history of the region. It shows how easily the old Middle East, marked by sectarian divides and ingrained rivalries, can re-emerge and stop change in its tracks.

There has long been bad blood between the Saudis and Iran. Saudi Arabia is a Sunni Muslim kingdom of ethnic Arabs, Iran a Shiite Islamic republic populated by ethnic Persians. Shiites first broke with Sunnis over the line of succession after the death of the Prophet Mohammed in the year 632; Sunnis have regarded them as a heretical sect ever since. Arabs and Persians, along with many others, have vied for the land and resources of the Middle East for almost as long.

These days, geopolitics also plays a role. The two sides have assembled loosely allied camps. Iran holds in its sway Syria and the militant Arab groups Hezbollah in Lebanon and Hamas in the Palestinian territories; in the Saudi sphere are the Sunni Muslim-led Gulf monarchies, Egypt, Morocco and the other main Palestinian faction, Fatah. The Saudi camp is pro-Western and leans toward tolerating the state of Israel. The Iranian grouping thrives on its reputation in the region as a scrappy “resistance” camp, defiantly opposed to the West and Israel.

For decades, the two sides have carried out a complicated game of moves and countermoves. With few exceptions, both prefer to work through proxy politicians and covertly funded militias, as they famously did during the long Lebanese civil war in the late 1970s and 1980s, when Iran helped to hatch Hezbollah among the Shiites while the Saudis backed Sunni militias.

But the maneuvering extends far beyond the well-worn battleground of Lebanon. Two years ago, the Saudis discovered Iranian efforts to spread Shiite doctrine in Morocco and to use some mosques in the country as a base for similar efforts in sub-Saharan Africa. After Saudi emissaries delivered this information to King Mohammed VI, Morocco angrily severed diplomatic relations with Iran, according to Saudi officials and cables obtained by the organization WikiLeaks.

As far away as Indonesia, the world’s most populous Muslim country, the Saudis have watched warily as Iranian clerics have expanded their activities—and they have responded with large-scale religious programs of their own there.

Reuters

Iran’s Supreme Leader Ayatollah Ali Khamenei (above, in 2008) has recently compared the region’s protests to Iran’s 1979 revolution.

In Riyadh, Saudi officials watched with alarm. They became furious when the Obama administration betrayed, to Saudi thinking, a longtime ally in Mr. Mubarak and urged him to step down in the face of the street demonstrations.

The Egyptian leader represented a key bulwark in what Riyadh perceives as a great Sunni wall standing against an expansionist Iran. One part of that barrier had already crumbled in 2003 when the U.S. invasion of Iraq toppled Saddam Hussein. Losing Mr. Mubarak means that the Saudis now see themselves as the last Sunni giant left in the region.

The Saudis were further agitated when the protests crept closer to their own borders. In Yemen, on their southern flank, young protesters were suddenly rallying thousands, and then tens of thousands, of their fellow citizens to demand the ouster of the regime, led by President Ali Abdullah Saleh and his family for 43 years.

Meanwhile, across a narrow expanse of water on Saudi Arabia’s northeast border, protesters in Bahrain rallied in the hundreds of thousands around a central roundabout in Manama. Most Bahraini demonstrators were Shiites with a long list of grievances over widespread economic and political discrimination. But some Sunnis also participated, demanding more say in a government dominated by the Al-Khalifa family since the 18th century.

Protesters deny that their goals had anything to do with gaining sectarian advantage. Independent observers, including the U.S. government, saw no sign that the protests were anything but homegrown movements arising from local problems. During a visit to Bahrain, Secretary of Defense Robert Gates urged the government to adopt genuine political and social reform.

But to the Saudis, the rising disorder on their borders fit a pattern of Iranian meddling. A year earlier, they were convinced that Iran was stoking a rebellion in Yemen’s north among a Shiite-dominated rebel group known as the Houthis. Few outside observers saw extensive ties between Iran and the Houthis. But the Saudis nonetheless viewed the nationwide Yemeni protests in that context.

Reuters

Saudi Arabian troops cross the causeway leading to Bahrain on March 14, above. The ruling family in Bahrain had appealed for assistance in dealing with protests.

In Bahrain, where many Shiites openly nurture cultural and religious ties to Iran, the Saudis saw the case as even more open-and-shut. To their ears, these suspicions were confirmed when many Bahraini protesters moved beyond demands for greater political and economic participation and began demanding a constitutional monarchy or even the outright ouster of the Al-Khalifa family. Many protesters saw these as reasonable responses to years of empty promises to give the majority Shiites a real share of power—and to the vicious government crackdown that had killed seven demonstrators to that point.

But to the Saudis, not to mention Bahrain’s ruling family, even the occasional appearance of posters of Lebanese Hezbollah leader Hassan Nasrallah amid crowds of Shiite protesters pumping their fists and chanting demands for regime change was too much. They saw how Iran’s influence has grown in Shiite-majority Iraq, along their northern border, and they were not prepared to let that happen again.

As for the U.S., the Saudis saw calls for reform as another in a string of disappointments and outright betrayals. Back in 2002, the U.S. had declined to get behind an offer from King Abdullah (then Crown Prince) to rally widespread Arab recognition for Israel in exchange for Israel’s acceptance of borders that existed before the 1967 Six Day War—a potentially historic deal, as far as the Saudis were concerned. And earlier this year, President Obama declined a personal appeal from the king to withhold the U.S. veto at the United Nations from a resolution condemning continued Israeli settlement building in Jerusalem and the West Bank.

The Saudis believe that solving the issue of Palestinian statehood will deny Iran a key pillar in its regional expansionist strategy—and thus bring a win for the forces of Sunni moderation that Riyadh wants to lead.

Iran, too, was starting to see a compelling case for action as one Western-backed regime after another appeared to be on the ropes. It ramped up its rhetoric and began using state media and the regional Arab-language satellite channels it supports to depict the pro-democracy uprisings as latter-day manifestations of its own revolution in 1979. “Today the events in the North of Africa, Egypt, Tunisia and certain other countries have another sense for the Iranian nation.… This is the same as ‘Islamic Awakening,’ which is the result of the victory of the big revolution of the Iranian nation,” said Ayatollah Ali Khamenei.

Iran also broadcast speeches by Hezbollah’s leader into Bahrain, cheering the protesters on. Bahraini officials say that Iran went further, providing money and even some weapons to some of the more extreme opposition members. Protest leaders vehemently deny any operational or political links to Iran, and foreign diplomats in Bahrain say that they have seen little evidence of it.

March 14 was the critical turning point. At the invitation of Bahrain, Saudi armed vehicles and tanks poured across the causeway that separates the two countries. They came representing a special contingent under the aegis of the Gulf Cooperation Council, a league of Sunni-led Gulf states, but the Saudis were the major driver. The Saudis publicly announced that 1,000 troops had entered Bahrain, but privately they concede that the actual number is considerably higher.

If both Iran and Saudi Arabia see themselves responding to external threats and opportunities, some analysts, diplomats and democracy advocates see a more complicated picture. They say that the ramping up of regional tensions has another source: fear of democracy itself.

Long before protests ousted rulers in the Arab world, Iran battled massive street protests of its own for more than two years. It managed to control them, and their calls for more representative government or outright regime change, with massive, often deadly, force. Yet even as the government spun the Arab protests as Iranian inspired, Iran’s Green Revolution opposition movement managed to use them to boost their own fortunes, staging several of their best-attended rallies in more than a year.

Saudi Arabia has kept a wary eye on its own population of Shiites, who live in the oil-rich Eastern Province directly across the water from Bahrain. Despite a small but energetic activist community, Saudi Arabia has largely avoided protests during the Arab Spring, something that the leadership credits to the popularity and conciliatory efforts of King Abdullah. But there were a smattering of small protests and a few clashes with security services in the Eastern Province.

The regional troubles have come at a tricky moment domestically for Saudi Arabia. King Abdullah, thought to be 86 years old, was hospitalized in New York, receiving treatment for a back injury, when the Arab protests began. The Crown Prince, Sultan bin Abdul Aziz, is only slightly younger and is already thought to be too infirm to become king. Third in line, Prince Nayaf bin Abdul Aziz, is around 76 years old.

Viewing any move toward more democracy at home—at least on anyone’s terms but their own—as a threat to their regimes, the regional superpowers have changed the discussion, observers say. The same goes, they say, for the Bahraini government. “The problem is a political one, but sectarianism is a winning card for them,” says Jasim Husain, a senior member of the Wefaq Shiite opposition party in Bahrain.

Since March 14, the regional cold war has escalated. Kuwait expelled several Iranian diplomats after it discovered and dismantled, it says, an Iranian spy cell that was casing critical infrastructure and U.S. military installations. Iran and Saudi Arabia are, uncharacteristically and to some observers alarmingly, tossing direct threats at each other across the Gulf. The Saudis, who recently negotiated a $60 billion arms deal with the U.S. (the largest in American history), say that later this year they will increase the size of their armed forces and National Guard.

And recently the U.S. has joined in warning Iran after a trip to the region by Defense Secretary Gates to patch up strained relations with Arab monarchies, especially Saudi Arabia. Minutes after meeting with King Abdullah, Mr. Gates told reporters that he had seen “evidence” of Iranian interference in Bahrain. That was followed by reports from U.S. officials that Iranian leaders were exploring ways to support Bahraini and Yemeni opposition parties, based on communications intercepted by U.S. spy agencies.

Saudi officials say that despite the current friction in the U.S.-Saudi relationship, they won’t break out of the traditional security arrangement with Washington, which is based on the understanding that the kingdom works to stabilize global oil prices while the White House protects the ruling family’s dynasty. Washington has pulled back from blanket support for democracy efforts in the region. That has bruised America’s credibility on democracy and reform, but it has helped to shore up the relationship with Riyadh.

A look at the Sunni-Shiite divide in the Middle East and some of the key flashpoints in the cold war between Saudi Arabia and Iran

The deployment into Bahrain was also the beginning of what Saudi officials describe as their efforts to directly parry Iran. While Saudi troops guard critical oil and security facilities in their neighbor’s land, the Bahraini government has launched a sweeping and often brutal crackdown on demonstrators.

It forced out the editor of the country’s only independent newspaper. More than 400 demonstrators have been arrested without charges, many in violent night raids on Shiite villages. Four have died in custody, according to human-rights groups. Three members of the national soccer team, all Shiites, have also been arrested. As many as 1,000 demonstrators who missed work during the protests have been fired from state companies.

In Shiite villages such as Saar, where a 14-year-old boy was killed by police and a 56-year-old man disappeared overnight and showed up dead the next morning, protests have continued sporadically. But in the financial district and areas where Sunni Muslims predominate, the demonstrations have ended.

In Yemen, the Saudis, also working under a Gulf Cooperation Council umbrella, have taken control of the political negotiations to transfer power out of the hands of President Ali Abdullah Saleh, according to two Saudi officials.

“We stayed out of the process for a while, but now we have to intervene,” said one official. “It’s that, or watch our southern flank disintegrate into chaos.”

Corrections & Amplifications

King Mohammed VI is the ruler of Morocco. An earlier version of this article incorrectly stated that the ruler was Hassan II.

—Nada Raad and Farnaz Fassihi contributed to this article.

We have Zero Tolerance for Sectarian Terrorism. Let there be no doubt. These Jihadis are turning on than that fed them during the Soviet Afghan War. Taliban are no different than any other Dogs of War, at the pay of any Master, who sponsors them.

Iran and Saudi Arabia have stabbed Pakistan on the back. They have taken undue advantage of our love and friendship and used our soil to fight their proxy battles. These two nations, whom Pakistanis have served to educate and taught them basic health care skills, have returned our favours by making our nation their killing field. They have brainwashed our people through their own tarnished brand of faith and used them through financial incentives, to fight their sectarian wars.

These Jihadis need to be arrested en masse in all cities of Pakistan and Deprogrammed by Islamic Scholars from all Fiqh of Islam. Without a massive deprogramming process, they will continue to create turmoil in Pakistan. Their heinous behavior involves attacking most weak and vulnerable. These cowards have chosen the defenceless, innocent, and peaceful Hazawal Pakistanis, who cannot fight back.

Quetta is not a playground for the Un-Islamic “Jihadi” Fanatics, funded by Saudis and Iran. Pakistani blood is not cheap it is precious. All Pakistanis need to close ranks and fight the Takfiri Jihadis. They do not represent Islam and its Core Values. Islam does NOT teach killing innocent men, women, and children, whether Muslims or Non-Muslim, or Atheists. Islam is a Deen, which protects the sanctity of human life and protects minorities.

The communist kafirs of the Evil Soviet Empire have been defeated. US forces is exiting Afghanistan in 2014. Takfiris should be offered a choice either get educated in a state registered Darul Uloom or be mainstreamed in an Islamic University. But, they should never be left by alone to practice their heinous ideology. Pakistan is not a battlefield for hire, for Iran versus Saudi Arabs Un-Islamic Sectarian Wars.

Reference

Posted by admin in Foreign Policy, Pakistan-US Relations on February 18th, 2013

My previous experience in Pakistan included looking down on Peshawar from the Khyber Pass in Afghanistan and receiving some rocket fire from the eastern side of the border while in Asadabad.

Despite this, I was aware that the media’s portrayal of Pakistan was not entirely accurate and I was looking forward to my stay at the Command and Staff College in Quetta. However, I never could have imagined how great an experience it would be.

The remainder of my career in the US Army will be spent working in South Asia. As part of my introduction to this career path, I had the opportunity to travel throughout Pakistan for a year, during my stay at the Command and Staff College. The purpose of the travel was to learn as much as I could about Pakistan, and South Asia, from political, economic, security, and cultural perspectives.

I discovered many things about this great country; primarily that the Pakistan represented in the global mass media is not an accurate reflection of the real Pakistan. I consider myself very lucky to have been able to experience the hospitality, beauty, and intrigue of this proud nation.

My travels and experience included most major cities, from Karachi, Lahore, Peshawar, and Islamabad, to the hills of Murree and Abbottabad, historical sites in Taxila and Ziarat, and the breathtaking beauty of Gilgit-Baltistan. I drove on the impressive and modern Motorway and on roads that have never been paved. I shopped in Anarkali Bazaar in Lahore and Park Towers in Karachi. I stayed at some of the finest hotels and spent a few nights in places that were not so nice. I met and dined with politicians, artists, shopkeepers, students, bishops, and others from almost every walk of life.

Courtesy: DAWN

Every person, no matter where they are from, will look for and find comfort in things that are familiar. This familiarity helps to ease feelings of isolation and ‘homesickness’.

As a white, Christian, Westerner you may wonder how I could find any comfort and familiarity in Pakistan, yet it was easy. I found many aspects of the culture and values in Pakistan to be quite familiar to me, and how I was raised. The mountainous, wooded areas near Murree and Abbottabad reminded me of my home states of Pennsylvania and Virginia.

The activities that I was able to engage in, such as playing sports in the Quetta Cantonment, fishing in Rawal Lake, having dinner at a nice restaurant in Karachi, or watching children play at a park in Lahore, are the same things that I would do at home in Virginia.

Despite these similarities, the most important aspect of familiarity was the military life. The fraternity of soldiers throughout the world is a close bond, and no matter what country, religion, race or creed they are from, soldiers will always have common stories, experiences, and struggles that they can share. All soldiers have experienced the cold, hunger, fear, loneliness, boredom, pride  I was duly impressed with the professionalism and expertise of the army. The advanced curriculum, modern capabilities, and forward thinking at institutions like the Infantry School and training centres demonstrate where the roots of success for the field formations lie. There is no doubt that the Pakistan Army is among the finest of contemporary militaries in the world.

I was duly impressed with the professionalism and expertise of the army. The advanced curriculum, modern capabilities, and forward thinking at institutions like the Infantry School and training centres demonstrate where the roots of success for the field formations lie. There is no doubt that the Pakistan Army is among the finest of contemporary militaries in the world.

I recognise that this experience can never be replicated. Although I missed my family every day, it was certainly the best year of my army career and one of the most fun, educational, and interesting experiences of my life. I was truly blessed with the friends I made at the Staff College, the Quetta community, and other places in Pakistan. God willing, we will meet again and I look forward to spending more time in this wonderful country of Pakistan.

The writer is a major in the US Army. The opinions expressed herein are his, and are not necessarily representative of the US Government, Department of Defense, or the US Army.