Why did the USA lose in Afghanistan?

Brig.Gen (Retd) Asif Haroon Raja

Pakistan Army

The US and its allies were drunk with power and took pride in their sophisticated war munitions, technology and wealth. They were sure to win the war irrespective of having no cause, and having sinister hidden motives. The Taliban had no resources but had an edge over their opponents in the intangibles. They had complete faith in Allah and were on the righteous path. Their faith is still unshakable, and are unpurchasable. Hence their total victory is a foregone conclusion.

Causes of the US defeat in Afghanistan

Insincere and mala fide intentions filled with prejudices and injustices.

Cooked up charges to invade Afghanistan, Iraq and Libya.

No grounds to wage a cruel war against so many Muslim countries.

No love lost for the Afghans, Iraqis, Libyans and Syrians, or any Muslim.

Minority non-Pashtun Afghans were empowered and majority Pashtuns sidelined and persecuted.

Pakistan which was instrumental in making the US the sole superpower, was mistrusted, ridiculed and penalized, while India which has no roots in Afghanistan, didn’t take part in the war on terror, and has been the biggest spoiler of peace, was trusted and made the main player by the US.

Despite allocating over a trillion dollars development funds, the US failed to better the lives of Afghans living in poverty stricken rural areas.

The US continued to back the inept, corrupt and unpopular regimes of Karzai and Ashraf Ghani (AG) and failed to establish a stable government in Kabul.

One trillion dollars were spent on raising, training and equipping the ANSF, but the US-NATO trainers failed to develop their moral fibre, sense of discipline, motivation and will to fight.

ISAF and ANA were pampered, heavily paid and provided luxuries, which made them comfort loving and drug addicts.

All the social crimes that were cleansed by the Taliban re-appeared and Afghanistan became the leading exporter of opium in the world.

Practice of ruthless bombings by jets and drones caused maximum deaths and injuries to the civilians; even funerals and weddings were not spared. Torture of prisoners and night raids were the tools widely used to break the will of opposing fighters. It gravitated the sympathies of the people towards the Taliban.

Too much trust in military might and no attention paid to winning the hearts and minds of the Afghans.

Weak military commanders who didn’t know much about Afghanistan’s geography, tribal history and culture, and terrain. They never strategized or modified tactics to grapple with the tactics of the resistance forces. The IEDs threat couldn’t be tackled. More so, they didn’t inspire their own troops, what to talk of the military contingents from 48 countries. Some top commanders were involved in love affairs and sex scandals.

Image Courtesy – Global Times, People’s Republic of China

The initial plan of occupying Afghanistan by the Western and Northern Alliance forces left much to be desired. The country was strategically ringed by establishing air bases in Tajikistan, Uzbekistan and Pakistan, but the inner circle was not contemplated to encircle and trap the leaders and fighters of the Taliban and Al-Qaeda. Probably avoidance of boots on ground to avoid casualties hindered this option.

It was a frontal invasion from the north by the Northern Alliance troops under the umbrella of airpower. Gigantic carpet bombing was carried out recklessly. With their rear areas safe, the defenders first withdrew to the caves of Tora Bora with ease, and then slipped into FATA. No effort was made to circle Tora Bora where all the wanted elements including OBL were present. Emphasis was on dropping tons and tons of molten lava from the air.

No effort was made to seal the porous and vulnerable border with Pakistan, again due to shortage of troops. Whole reliance was on Pakistan but it had to be a collective effort to make the concept of anvil and hammer successful. The reason was that the US wanted the border with Pakistan to remain open for clandestine use by the RAW-NDS. That’s why the Kabul regime and the US strongly objected to fencing of western border by Pakistan.

The ISAF made up of 48 military contingents including 28 from NATO fought the war without initial battle inoculation, and acquisition of basic knowledge of geography, terrain, culture of tribes, meaning of Pashtunwali, and training in guerrilla warfare. No motivational training was given to the troops to inculcate in them the will to fight and die. Except for top commanders, none knew the aims and objectives of the war.

Opening of the second front in Iraq in 2003 when the Afghan front was fluid, indulgence in covert wars, and hybrid war were at the cost of consolidating gains in Afghanistan through development and education. Only important capitals were finely developed while the vast rural areas were neglected. The two-front war resulted in distraction and division of resources and enabled the Taliban to bounce back in 2006.

The real war started in 2009 after the two troop surges swelling the combat strength of the ISAF from 8000 to 1, 40,000, but Gen McChrystal lost heart in the first major offensive in Helmand due to heavy casualties of the ISAF.

Biggest mistake made was when the ISAF troops were withdrawn backwards and bunkered in the safety of 8 military bases in capital cities in 2009. The entire rural belt in the eastern and southern Afghanistan was vacated thereby allowing the Taliban to gain initiative and a military edge over the occupiers and their collaborators.

Obama should have exited from Afghanistan after he concluded that it was an unwinnable war, and the main mission of killing OBL and professed destruction of Al-Qaeda had been accomplished. Clinging on to Afghanistan for next nine years on the insistence of Pentagon and Resolute Support Mission commanders was militarily unsound. This inordinate delay swelled the avoidable human and financial losses of occupational troops as well as of the ANSF and the civilians.

The next mistake made by Obama was his broadcasted plan to withdraw troops by Dec 2014. The thinning out started in July 2011 and by 2013 frontline security was handed over to the ANA. It demoralized the ANA, snatched the fighting spirit of the ISAF whose troops wanted to return home alive and in one piece, spurred the Taliban and they stepped up their offensive. Their momentum accelerated from 2015. From that time onwards, the US for all practical purposes had lost the war, but due to pressure from the Pentagon, the US kept reinforcing failure.

To avoid body bags, Obama introduced the deadly pilotless drones as a choice weapon of war. Disproportionate use of drones was cowardly and unethical.

The US didn’t seriously negotiate with the Taliban between 2006 and 2014 when it was strong on ground and became serious in 2018-19 when it had become weak.

The decentralized Taliban field commanders under one Ameerul Momenein Mullah Omar outclassed the ISAF commanders in strategy and tactics. No change came in their vigor under Mullah Mansour and incumbent Mullah Haibatullah. New recruits kept getting enrolled and the numbers swelled.

The US spent more time on blame game rather than focusing on its primary mission of stabilizing Afghanistan. By blaming Pakistan, Haqqani Network and Quetta Shura for its political and military failures, the US tried to cover up its fault lines. This blame-game continued even after all the terrorist groups were flushed out of FATA in 2015

Trump tried to salvage the fast deteriorating security situation but failed and ultimately had to sign a peace agreement with the Taliban at Doha in February 2019. All foreign troops were to withdraw by May 2021. That was another turning point in the fortunes of the Taliban since the historic agreement had given them recognition and enhanced their stature internationally.

Yet another defining moment came when Joe Biden announced on April 14, 2021 that the longest war will be winded up and all foreign troops would pull out by Sept 11, 2021. This date was advanced to August 31.

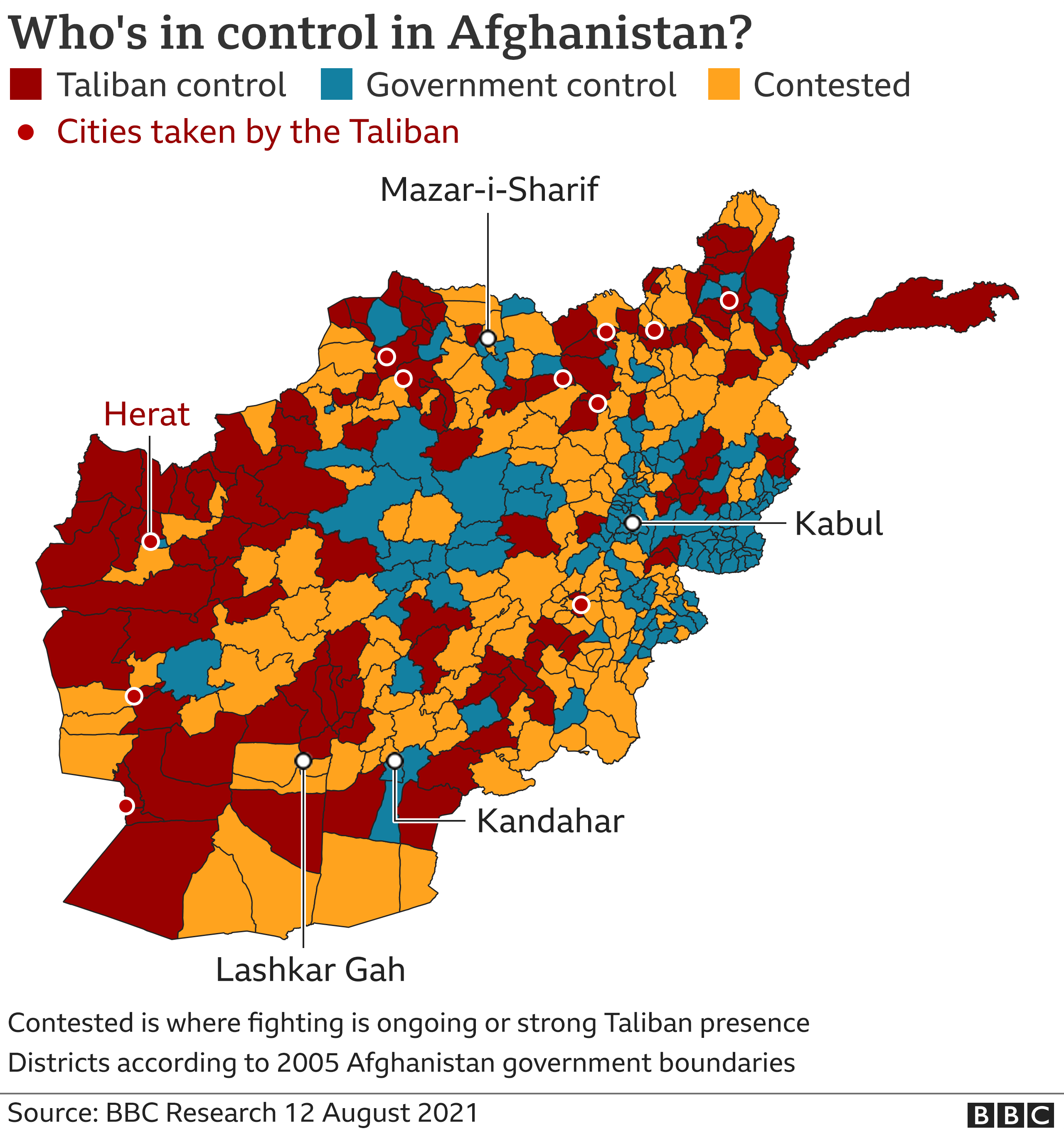

All roads in Afghanistan were opened for the triumphant Taliban to race forward and capture as much territory in May, June and July. With 80% territory and most trade transit points in the control of the Taliban, the final phase to capture cities that are already under their siege is likely to start after August 31, or Sept 11. For the ANA, the summer period up to Oct/early November is tough.

Endgame

In the endgame, the losers have suddenly changed their stance from a military solution to a peaceful solution of the tangle. Their narrative of blaming Pakistan for the instability in Afghanistan has been modified and now the Taliban are painted as violence prone and anti-peace.

While the winning Taliban have expressed their willingness to accommodate all less Ashraf Ghani (AG) and his team, the US and the whole world in general including Pakistan are standing behind the unpopular regime in Kabul and are pressuring Taliban to share power with AG and accept him as the elected president till next elections. The spoilers as well as others are also against the basic demand of the Taliban to establish Islamic Emirate.

This change of narrative clubbed with a petrifying story that there will be chaos, prolonged civil war, bloodshed and refugee exodus due to Taliban’s obstinacy and fancy for bloodletting, has drifted the attention of the world from the stupefying victory of the Taliban and disgraceful defeat and abrupt exit of the US forces. Whole focus has shifted to the future horrid scenario of Afghanistan based on premeditated assumptions.

For 20 years the world quietly stomached the brutalities of the mad adventurers wanting to bludgeon Al-Qaeda and the Taliban without a murmur. A minority government of non-Pashtuns remained in power and the majority Pashtuns remained in the backwoods.

And now when the Taliban are getting closer to regain power which was illegally snatched from them, the world led by the spoilers of peace are giving sermons of peace to the winners and advising them that there is no military solution to Afghan crisis.

The infatuation of the US for the puppet regime in Kabul is so passionate that the US has announced its full diplomatic and financial support to it and air support to the shaky ANA. While Pakistan is in two minds, China is unhesitant in extending full support to the Taliban and to fill the power vacuum in Afghanistan.