In his first inaugural address, back in 2009, Barack Obama announced: “To the Muslim world, we seek a new way forward, based on mutual interest and mutual respect.” Improving how the US was perceived among the world’s 1.6 billion Muslims was not about winning an international popularity contest but was deemed as vital to US national security. Even the Pentagon has long recognized that the primary cause of anti-American Terrorism is the “negative attitude” toward the US: obviously, the reason people in that part of the world want to attack the US — as opposed to Peru or South Africa or China — is because they perceive a reason to do so.

Obama’s most devoted supporters have long hailed his supposedly unique ability to improve America’s standing in that part of the world. In his first of what would be many paeans to Obama, Andrew Sullivan wrote back in 2007 that among Obama’s countless assets, “first and foremost [is] his face,” which would provide “the most effective potential re-branding of the United States since Reagan.” Sullivan specifically imagined a “young Pakistani Muslim” seeing Obama as “the new face of America”; instantly, proclaimed Sullivan, “America’s soft power has been ratcheted up not a notch, but a logarithm.” Obama would be “the crudest but most effective weapon against the demonization of America that fuels Islamist ideology” because it “proves them wrong about what America is in ways no words can.” Sullivan made clear why this matters so much: “such a re-branding is not trivial — it’s central to an effective war strategy.”

None of that has happened. In fact, the opposite has taken place: although it seemed impossible to achieve, Obama has presided over an America that, in many respects, is now even more unpopular in the Muslim world than it was under George Bush and Dick Cheney.

That is simply a fact. Poll after poll has proven it. In July, 2011, the Washington Post reported: “The hope that the Arab world had not long ago put in the United States and President Obama has all but evaporated.” Citing a poll of numerous Middle East countries that had just been released, the Post explained: “In most countries surveyed, favorable attitudes toward the United States dropped to levels lower than they were during the last year of the Bush administration.”

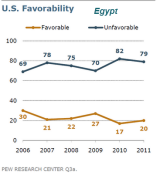

A 2011 Arab American Institute poll found that “US favorable ratings across the Arab world have plummeted. In most countries they are lower than at the end of the Bush Administration, and lower than Iran’s favorable ratings.” The same year, a poll of public opinion in Egypt — arguably the most strategically important nation in the region and the site of Obama’s 2009 Cairo speech — found pervasively unfavorable views of the US at or even below the levels of the Bush years. A 2012 Pew poll of six predominantly Muslim nations found not only similar or worse perceptions of the US as compared to the Bush years, but also documented that China is vastly more popular in that part of the world than the US. In that region, the US and Israel are still considered, by far, to be the two greatest threats to peace.

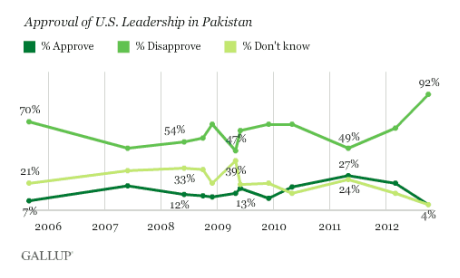

In sum, while Europeans still adore Obama, the US is more unpopular than ever in the Muslim world. A newly released Gallup poll from Thursday, this one surveying public opinion in Pakistan, provides yet more powerful evidence of this dangerous trend. As Gallup summarized: “more than nine in 10 Pakistanis (92%) disapprove of US leadership and 4% approve, the lowest approval rating Pakistanis have ever given.” Worse, “a majority (55%) say interaction between Muslim and Western societies is ‘more of a threat’ [than a benefit], up significantly from 39% in 2011.” Disapproval of the US in this nuclear-armed nation has exploded under Obama to record highs:

In sum, while Europeans still adore Obama, the US is more unpopular than ever in the Muslim world. A newly released Gallup poll from Thursday, this one surveying public opinion in Pakistan, provides yet more powerful evidence of this dangerous trend. As Gallup summarized: “more than nine in 10 Pakistanis (92%) disapprove of US leadership and 4% approve, the lowest approval rating Pakistanis have ever given.” Worse, “a majority (55%) say interaction between Muslim and Western societies is ‘more of a threat’ [than a benefit], up significantly from 39% in 2011.” Disapproval of the US in this nuclear-armed nation has exploded under Obama to record highs:

It is not hard to understand why this is happening. Indeed, the slightest capacity for empathy makes it easy. It is not — as self-loving westerners like to tell themselves — because there is some engrained, inherent, primitive anti-Americanism in these cultures. To the contrary, there is substantial affection for US culture and “the American people” in these same countries, especially among the young.

What accounts for this pervasive hostility toward the US is clear: US actions in their country. As a Rumsfeld-era Pentagon study concluded: “Muslims do not ‘hate our freedom,’ but rather, they hate our policies.” In particular, it is “American direct intervention in the Muslim world” — justified in the name of stopping Terrorism — that “paradoxically elevate[s] the stature of and support for Islamic radicals.”

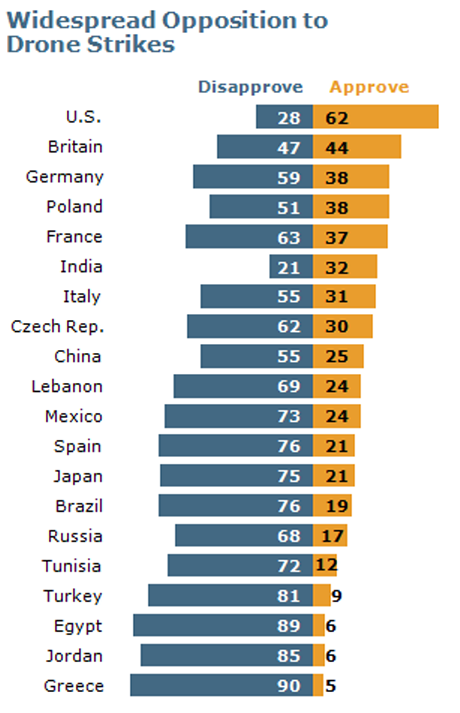

Just consider how Americans view their relentless bombing attacks via drone versus how the rest of the world perceives them. It is not hyperbole to say that America is a rogue nation when it comes to its drone wars, standing almost alone in supporting it. The Pew poll from last June documented that “i n nearly all countries, there is considerable opposition to a major component of the Obama administration’s anti-terrorism policy: drone strikes.” The finding was stark: “in 17 of 20 countries, more than half disapprove of U.S. drone attacks targeting extremist leaders and groups in nations such as Pakistan, Yemen and Somalia.” That means that “Americans are the clear outliers on this issue”:

In sum, if you continually bomb another country and kill their civilians, not only the people of that country but the part of the world that identifies with it will increasingly despise the country doing it. That’s the ultimate irony, the most warped paradox, of US discourse on these issues: the very policies that Americans constantly justify by spouting the Terrorism slogan are exactly what causes anti-American hatred and anti-American Terrorism in the first place. The most basic understanding of human nature renders that self-evident, but this polling data indisputably confirms it.

Last month, the Atlantic’s Robert Wright announced that he would cease regularly writing for that magazine in order to finish his book on Buddhism. When doing so, he wrote an extraordinarily (though typically) great essay containing all sorts of thought-provoking observations. Yesterday, the blogger Digby flagged the key passage relating to the issue I’m raising today; please read this:

“[1] The world’s biggest single problem is the failure of people or groups to look at things from the point of view of other people or groups — i.e., to put themselves in the shoes of ‘the other.’ I’m not talking about empathy in the sense of literally sharing people’s emotions — feeling their pain, etc. I’m just talking about the ability to comprehend and appreciate the perspective of the other. So, for Americans, that might mean grasping that if you lived in a country occupied by American troops, or visited by American drone strikes, you might not share the assumption of many Americans that these deployments of force are well-intentioned and for the greater good. You might even get bitterly resentful. You might even start hating America.

“[2] Grass-roots hatred is a much greater threat to the United States — and to nations in general, and hence to world peace and stability — than it used to be. The reasons are in large part technological, and there are two main manifestations: (1) technology has made it easier for grass-roots hatred to morph into the organized deployment (by non-state actors) of massively lethal force; (2) technology has eroded authoritarian power, rendering governments more responsive to popular will, hence making their policies more reflective of grass roots sentiment in their countries. The upshot of these two factors is that public sentiment toward America abroad matters much more (to America’s national security) than it did a few decades ago.

“[3] If the United States doesn’t use its inevitably fading dominance to build a world in which the rule of law is respected, and in which global norms are strong, the United States (and the world) will suffer for it. So when, for example, we do things to other nations that we ourselves have defined as acts of war (like cybersabotage), that is not, in the long run, making us or our allies safer. The same goes for when we invade countries, or bomb them, in clear violation of international law. And at some point we have to get serious about building a truly comprehensive nuclear nonproliferation regime — one that we expect our friends, not just our enemies, to be members-in-good-standing of.”

Whenever I write about how the US is so deeply unpopular in the Muslim world (and getting more unpopular), it invariably prompts tough-talking, swaggering, pseudo-warriors who dismiss the concern as irrelevant: who cares what They think of Us? The reason to care is exactly what Wright explained: even if you dismiss as irrelevant the morality of constantly bombing and killing other people, nothing undermines US interests and security more than spreading anti-US hatred in the world. Put another way, it is precisely those people who support US aggression by invoking the fear-mongering The Terrorists! cliche who do the most to ensure that this threat is maintained and inexorably worsens. And, as Wright says, it is only a complete lack of empathy for other people’s perspectives that can explain this failure to make that connection.

Imagine Ad

Probably the single best ad of the 2012 presidential cycle was this one, entitled “Imagine,” produced independently by supporters of the Paul campaign:

In 1978, the Rohingya were stripped of their citizenship in 1982 and became the perfect foil for rampant human rights abuse, including slave labour and torture, that led to a second exodus into Bangladesh in 1991-1992. (Source: The Guardian)

In 1978, the Rohingya were stripped of their citizenship in 1982 and became the perfect foil for rampant human rights abuse, including slave labour and torture, that led to a second exodus into Bangladesh in 1991-1992. (Source: The Guardian)