Alexander of Macedonia (Sikander-i-Azam)

Back in 2001, when I was making the PTV documentary Sindhia mein Sikander (on Alexander’s Indian campaign), I discovered a large body of local myth. One was the ridiculous pride that everyone took in the fact that Alexander of Macedonia tarried in their village for ‘six months’ — always six, never more, nor less. The other, a Multan-centric one, was about how the people of that city killed the conqueror.

Having sailed down the Jhelum from the vicinity of Mandi Bahauddin, to its junction with the Chenab near Jhang, Alexander made forced marches across what was then sand desert, through modern Toba Tek Singh to Kamalia, Tulumba and eventually Multan — “the principal town of the Mallian people”, as the historian Arrian tells us.

The city of Multan lay around the lofty battlements of a strongly fortified citadel with two perimeter walls that stood in the area taken by the tomb of Rukne Alam today. Alexander led the attack with one division supported by another, under his general Perdiccas. Alexander’s troops managed to take down a gate, massive as it must have been, penetrating into the first corridor.

As the foreigners milled about in the corridor between the two defensive walls, they saw above them the battlements virtually crawling with the defenders. As Alexander ordered sapping operations, he also called for scaling ladders to be put up against the walls. Impetuous as he was, Alexander did not like the slow progress. Snatching a ladder from the man carrying it, Alexander personally placed it against the wall and, crouching under his shield, clambered up to the crenulations.

Immediately behind him was Peucestas, carrying the sacred shield that Alexander always used in battle. Following Peucestas was Leonnatus, the king’s personal bodyguard.

Having reduced the defenders on the battlements, Alexander stood on the crenulations in full view of both the defenders and his own troops. While his troops were hurrying to join him on the fort walls, Alexander jumped inside the fort where he met the best of the Rajput troops from Multan and as far away as Rajasthan. In the thick of this battle, as he raised his sword arm to strike an adversary, an arrow from a Multani archer found its target.

The arrow, having pierced his corselet, lodged in his breast on the right side. Alexander fell. We are told that he bled from the mouth, the blood being mixed with air bubbles, meaning that his lung was punctured. There is then a very moving heroic scene preserved in the histories: Perdiccas standing astride the still body, protecting it with the shield of Achilles, and Leonnatus desperately holding off the attackers.

Meanwhile, Alexander’s panicked soldiers had gained the wall by escalade. Soon the gates were thrown open and the fort taken. Though he gave his army a fright, Alexander did not die. He made it back by the skin of his teeth. This was September 326 BCE.

Four years later, in June 322, Alexander died apparently of a fever in Babylon. In between the injury in Multan and his final exit from near Gwadar, Alexander fought several battles, notably those of Rahim Yar Khan, Sehwan and Hyderabad. And he survived the horrendous march across the parched wastes of Makran. Yet so many in Multan believe he died of their arrow.

It is said, in jest of course, that the Multani phrase ‘karay saan,’ (will do) means something may (or may not) get done in the next several years after the utterance. I joke with my Multani friends that if they want to believe it was their arrow that killed the Macedonian, then we must also take the karay saan joke at face value. Surely only such an arrow could have taken four years to kill a man.

Published in The Express Tribune, July 23rd, 2011.

Alexander and the Macedonians in the Indus River Valley

From Samarkand Alexander returned to Kabul. From Kabul the army marched east. Roxanne was not the only wife journeying with the army. Altogether there were approximately 30 thousand camp followers, including several thousand children. These were the children of the soldiers and their wives. The number of soldiers was in the neighborhood of eighty thousand.

This horde passed through the desolate area east of Kabul. The main army, under the command of Alexander’s companion Hephaistion, traveled through the Khyber Pass into the vicinity of Peshawar. Alexander took a smaller group on an alternate route which arrived in the Indus Valley upriver from Peshawar.

The ruler of Taxila had already made contact with Alexander and submitted to his overlordship. Upriver from Taxila there was refuge called Aornos. Aornos was situated on a plateau facing the river and protected by steep sides. Historical legend had it that the Greek man-god Hercules had tried to take Aornos and failed.

Alexander decided to capture Aornos for a number of reasons. First its capture would tell the people of the region that there was no escaping Alexander. Second, it would eliminate a possible center of resistance to his later rule. Third, it was a challenge for Alexander to outdo Hercules, whom he counted as one of his ancestors on his mother’s side.

The main army under Hephaistion joined Alexander in the march to Aornos. At Aornos Alexander saw that an assault up the hillside on which it was located would probably fail. He found from local sources that there was a trail that led into the area above Aornos. The entrance to the trail was about five miles away. Alexander took the army and their siege equipment over this difficult trail. Where the trail came to Aornos there was a ravine about 1600 feet across and 100 feet deep. Alexander set the army to work building a causeway across the ravine. The catapults were used to bombard the defense force at Aornos. The defenders knew that it was just of matter of time before Alexander’s forces captured Aornos. At night Alexander used a clever and ruthless trick to final destroy the defenders. He left guards off one escape route. The defenders thought it was an mistake and took the opportunity to try to make an escape. But it was not a mistake. Alexander had his troops lying in ambush and when the defenders of Aornos came out they were massaacred by Alexander’s troops.

After the victory at Aornos Alexander was ready to conquer the rest of the region. Many rulers capitulated to Alexander. One ruler who did not was Porus who ruled a kingdom along the Hydaspes (Jhelum) River. This was in the region of Indus Valley called the Punjab, the five river region. Alexander’s army was vastly superior to Porus’ in numbers, equipment and experience. Porus hoped only to hold up the Macedonian army’s crossing of the Jhelum River until the monsoon rains would swell the river to the point that it would be impossible for the army to cross.

Porus had an army of thirty thousand soldiers with two thousand of them cavalry. He had in addition three hundred war elephants, the ancient equivalent of tanks. Against any other opponent the force would have been formidable, but against Alexander’s forces it was pitiable.

Alexander arrayed his forces so as to make it uncertain where the crossing of the Jhelum River would take place. Porus had to disperse his already indadequate forces opposite the places where Alexander’s forces could be seen to be concentrated. But all of the visible concentrations were merely for show. The real crossing force Alexander managed to hide in a bend in the river as shown below.

Alexander’s crossing force consisted of five thousand cavalry and four thousand infantry. The two crossings required were relatively easy with the river water often only chest high. The crossing commenced at night so that the force would be on the other side by dawn. When Porus was informed of the crossing he sent a force of two thousand men with fifty chariots under the command of his son. The chariots got mired in mud and all of them were lost. Porus’ son was killed. Porus then directed his main force to the crossing. The battle was a decisive victory for the Macedonians. About one third of Porus’ army was killed and one third captured including Porus himself. The war elephants caused some problem for the Macedonians but not much. The elephant drivers, the mahouts, were killed by Alexander’s archers and the elephants themselves were maimed. The elephants once blinded and their trunks cut by swords were as much of a danger to Porus’ forces as the Macedonians.

Porus’ capture did not result in his execution for holding up Alexander’s advance through India as might have been expeted. When the captured Porus was brought before Alexander asked him, “How do you want me to treat you?” Porus answered “Like a king.” This answer had two interpretations: 1. Treat me like the king that I am. 2. Treat me with the generosity of the noble king that you, Alexander, are. This answer pleased Alexander and he must have been in a good mood, perhaps even in a manic mood, because he freed Porus and gave him back the rulership of his kingdom under Alexander’s overlordship. Alexander even added some new territory to Porus’ kingdom. Alexander’s treatment of Porus fits in with mythology of the times; i.e., that monarchs are special, noble people ordained by the gods to rule and deserving of regal treatment even in defeat.

The spectacular victory over Porus precipitated a crisis for the Macedonians. After that victory it was clear that no one could stop the Macedonians. Alexander wanted to march east into the Ganges River Valley. It was not far from the site of the defeat of Porus. With the support of Porus’ kingdom the invasion of the Ganges River Valley would not be difficult. The problem was the army. Alexander did take the army in the direction of the Ganges Valley. When they reached the Beas River the soldiers refused to cross it. They were tired of campaigning and worried that they would never see their families back in Macedonia again. The climate of India was taking its toll. Tropical disease was much more of a threat in hot, humid India than it had been in desert and mountains of central Asia.

When Alexander called for the army to march east the soldiers refused to go. It was virtually mutiny, but Alexander had promised them when the campaign first began that he would not rule them as a tyrant. In the face of their refusal to continue he acquiesed and agreed to head back to Macedonia. He did however sulk in his tent for a few days.

The army returned to the Jhelum River where it made preparation for the journey down river. When the army did move down the Indus River Valley it did so in three branches. There was a fleet of ships and boats which traveled down the Indus River. Alexander joined this branch. Another branch traveled on the east side of the river under the command of Hephaistion and the third branch on the west side under Craterus. There was much fighting as Alexander insisted on destroying any opposition along the way which might be a threat to his future rule of the Indus region.

At the city of Multan Alexander led the assault and was hit by an arrow in the chest. He and three of his guards had been trapped in the city alone when a siege ladder broke. Two of his companions were killed by the city’s defenders and Alexander would have been killed also if the Macedonians had not just in time broke through a city gate. The attackers thought Alexander had been killed and they took revenge on the city defenders. But Alexander was still alive and surgeons cut out the arrow. From the description of the surgery, which implied a perforated lung, it seems hardly credible that he could have survived. But he did survive and recovered enough that in a few days he could ride a horse. The people of Multan did not survive. The Macedonian massacred the entire population in revenge for Alexander’s wound.

Along the way Alexander founded yet another Alexandria, this one called Alexandria at the Confluence. The confluence was of the Jhelum and Beas Rivers. This Alexandria is now the city of Uchch.

One part of the army separated and marched through what is now southern Afghanistan and Iran. When the rest of the army reach Patala the fleet went to the coast to embarck on the voyage west. Alexander with the remainder of the army and the camp followers marched west initially north of the Makran Desert. In part, the reason for Alexander ordering this difficult overland march was to arrange for supplies for the ships along the coast. Perhaps the other part of the reason was because it was a challenge.

The Return Journey

The march of the main force of Alexander’s army was complicated by the increase in its size due to the incorporation of forces and camp followers from the Indus region. Initially Alexander chose a route north of the coast to avoid the extreme desert. The route he chose was still desert but not so extreme as the coast. However in the Kech River Valley there is a danger of flash floods from rainstorms in the nearby mountains. Natives in such regions know not to tarry in the dry stream beds, particularly not to camp there. It would have been difficult for Alexander’s army as large and slow moving as it was to avoid such stream beds. The flash floods came and washed away much of the supply trains with their food, water and equipment. There was tremendous loss of life among the camp followers as well.

The loss of food and water led to later losses during the march in the desert. Everyone suffered privation. No one had as much water as needed. At one point his men scrounged enough water to give Alexander a helmet-full. Alexander, in a dramatic gesture, poured the water into the sand rather than drink while his men could not. His men must have thought that it was a shame he did not choose an equally dramatic way of expressing the same thought without wasting the precious water.

The army reached an oasis at Turbat and rested and replenished supplies there.

At this point Alexander took the army to the coast rather than the easier route through what is now Iran. He apparently was wanting to make contact with his fleet which might be short of water and food. At the coast, where Pasni is now, Alexander had his troops dig wells as a source of water for ship traversing the coast. He was not able to find the fleet at that time however.

From Pasni Alexander took the army on a route along the coast through the Makran Desert. The terrain is so desolate that it encourages comparison with Mars. In some places the plain is encrusted with salt that makes plant growth virtually impossible.

After a journey of about a hundred miles through the Makran Desert Alexander turned the army away from the coast and marched to the city that is now called Bampur and from there on to Salmous where his route crossed paths with contingent that took the more northerly route from the Indus Valley through what is now Afghanistan and southeastern Iran. From Salmous he journeyed down to the coast at the Strait of Hormuz where he found the fleet under the command of Nearchus. The fleet had had difficulties but had survived.

The fleet went on to Mesopotamia and Alexander returned to Salmous and headed west to the site of the Persian capital of Persepolis. After the march of about 600 miles from the Indus there must have been considerable remorse among the Macedonians that they had torched the city after a drunken orgy the last time they were there. Alexander himself expressed such remorse.

From Persepolis the army traveled on to the city of Susa, where the most notable happening was the arranged mass marriage of about one hundred of the higher officers of the army with Persian brides. Alexander and Hephaistion also married Persian brides at this time, the daughters of Darius, who had been captured at the Battle of Issus. Ten thousand of the common soldiers also took Persian brides in the mass marriage. Alexander’s regime was becoming more Persian in personnell and practices and he showed little interest in Macedonia.

From Susa Alexander took the army along the coast of the Persian Gulf to the mouth of the Euphrates. There he founded yet another Alexandria, the last as it would turn out. He went by boat up the Eurphrates past the turnoff to Babylon to the city of Opis.

In Opis there was a sinister episode. In a confrontation with his Macedonian veterans he threatened to raise a new army from among the Persians. When some spoke out against him Alexander jumped into the crowd and singled them out and sent them to their death by execution.

From Opis he took the army to Ecbatana (Hamadan), an important administrative center for the Persian Empire. It was a higher altitude and a more pleasant climate. Alexander and many of his soldiers indulged in marathon drinking binges. Some drank so much that they died. One of those who died was Alexander’s close companion Hephaistion.

Alexander and Hephaistion had been friends since boyhood. They even resembled each other quite a bit. One notable difference was that Hephaistion was taller than Alexander. When Alexander captured Darius’ family at the Battle of Issus Darius’ mother came to plead for their safety. When she entered Alexander’s tent she took Hephaistion who was taller to be Alexander. After she addressed Hephaistion as Alexander and then found she had made an error she was fearful that all was lost, but Alexander raised her up and he told her that everything was alright because Hephaistion was Alexander too.

So Hephaistion was Alexander’s friend, lover and lifelong companion, even his alter ego and now he was dead. Alexander was devastated. He lay on Hephaistion’s body all day and night. He seemed to have lost his senses. He tried to have Hephaistion worshiped as a god but the priests said Hephaistion’s celebration as a hero was the best that could be done. Alexander called for a furneral pyre for Hephaistion that was five stories tall and cost many fortunes.

It was perhaps at this point that Alexander began worrying that the gods had deserted him. Alexander’s religiousness was what would be called superstitiousness today. He began to see ominous signs. The most ominous of these involved an elderly Hindu priest who had joined Alexander’s entourage. The elderly man finding himself nearing death decided to burn himself on a funeral pyre. He said goodbye to all of Alexander’s companions but said to Alexander, “We will say our goodbyes in Babylon.”

This omen led Alexander to postpone and procrastinate about entering Babylon. When Alexander did enter Babylon there were crows fighting above the city wall, another evil omen. Yet Alexander continued to drink to excess. A month before his 33rd birthday he became ill with a fever and the fever worsened. Soon he was barely able to speak. He was asked to whom the empire should go Alexander whispered, “To the strongest of course!”

About ten days before he would have become 33 years of age Alexander, the ruler of a world empire he had created himself, died.

Was Alexander Manic-Depressive? Was He an Alcoholic?

Alexander was responsible for ruthless atrocities, but so were most leaders of that time. What was different about Alexander was a bipolarity. Contemporaries spoke of his charm and boundless energy. Others spoke of his brooding and murderous intolerance and that he was thought to be “melancholy mad.” His gestures of generousity were well known, but so were his atrocities.

Here are some of the black deeds he was responsible for:

- The city of Thebes, one of the major cities of Greece, defied him and order it sacked and destroyed and the Thebans massacred.

- A man known as Black Cleitus had fought for Alexander’s father Philip. He fought for Alexander and saved his life at the Battle of Granicus. Alexander in Samarkand announced his intention of appointing Cleitus satrap (provincial governor) of Bactria. At the banquet celebrating the appointment Alexander got drunk and began disparaging his father Philip. Cleitus challenged Alexander’s statement and told Alexander that all his glory was due to his father. This made Alexander furious and when Cleitus made another remark Alexander stabbed him with a javelin, killing him.

- In what is now western Afghanistan there was an episode called the Conspiracy of the Pages. A group among the pages that served Alexander decided to kill him. They arranged to be on duty all at the same time. The plot was foiled only by Alexander carousing all night and not coming home. A royal attendant heard of the plot and reported it to Philotas, the son of Alexander’s top general Parmenio. Philotas failed to report the conspiracy of the pages to Alexander and Alexander not only had the pages executed (by stoning) but also Philotas. Philotas’ father, Parmenio, had been left in the city of Hamadan in what is now Iran. Before Parmenio could hear of the fate of his son Alexander sent assassins to kill him. Thus Alexander repaid the past services of Parmenio.

- In Bactria Alexander ordered the massacre of the descendants of Greek priests who had collaborated with the Persian king on the Ionian coast a hundred and fifty years before. The Greeks in that city had done nothing to indicate that they would be anything other than most loyal subjects for Alexander. They greeted him with great joy and he had them butchered.

These episodes can be compared with his generous treatment of Porus who held up Alexander’s campaign for months.

The contradictions in his behavior are easily explained by his being afflicted with the manic-depressive syndrone, also called the bipolar syndrome. People who have been afflicted with manic-depressive syndrome and written about it give some understanding of how difficult it is for others to appreciate the seriousness of the condition. The writer William Styron says that his depressive episode were so terrible that he would rather have a limb amputated than go through one of them. A psychiatrist, Kay Redfield Jamison, who was also a manic-depressive says that the manic episodes were like skating on the rings of Saturn.

It would have been difficult enough for Alexander to constrain his impulses given his status and the adulation he received. When this was compounded with the manic-depressive syndrome it is not surprising that the results would be bizarre. The end result was a life that reads like the script of a modern movie of an Anti-Christ, a figure who leads a charmed life and has a meteoric rise to power because he is the offspring of the Devil. Alexander himself was the father of at least two children. Roxanne bore him a son at the time of the Indus Valley campaign but that son died in infancy. After the death of Hephaistion Alexander conceived another child with Roxanne, another son who did survive infancy. He lived to be about ten, at which time he was a possible threat to the kingships of Alexander’s generals. He and his mother Roxanne were killed to remove that threat. Alexander had married a second wife, one of the daughters of Darius. Roxanne had her killed long before Roxanne herself was killed. There were rumors of children of Alexander by other women but they disappeared, if they ever really existed.

Sources:

- Michael Wood, In the Footsteps of Alexander The Great: A Journey from Greece to Asia, University of California Press, 1997.

A. B. Bosworth, Alexander and the East: The Tragedy of Triumph, Clarendon Press, Oxford, 1996.

One of the most beautiful and poetic passages about Alexander the Great is found in the Holy Koran. The Koran refers to Alexander as Dhul-Qarnain (also spelled Zhul-Qarnain or Zulkarnein), meaning ‘The Lord with the Horns’. To appreciate this passage, you might like to have a basic idea of the structure of the Koran.

The Koran (or Quran) means ‘The Recital’. The words of the Koran are the words of Allah (God) revealed to Mohammed(SAW) through the angel Gabriel. Mohammed(SAW) (570-632 AD) retold these revelations in public speeches, which were in turn recorded by scribes. This collection of speeches make up the 114 chapters or ‘suras’.

Most suras refer to persons known to both Jews and Christians as well as Muslims: the stories of Adam(SAW) , Abraham(SAW) , Moses(SAW) and many other prophets. Only sporadically a story is entirely retold. Most texts start with a brief reference, then concentrate on the interpretation: the final explanation of the story in God’s own words. So the texts basically run: If people question you about Moses, tell them… ; When they ask you about Jesus, tell them… . It is clear that all of these stories were very well known to Mohammed’s audience. There was just no need to retell them. It was the explanation which mattered.

The same is the case with Alexander. In the sura ‘The Cave’ the Koran reads: “They will ask you about Dhul-Qarnain. Say: I will give you an account of him.” Thus, the Koran treats Alexander the Great in the same way as it treats Noah(SAW) , Jesus(SAW) , King Solomon(SAW) and others.

What follows is an account – of roughly 300 words – which explains the nature of Alexander. In essence it is stressed that Alexander was an instrument in the hands of Allah. God deliberately bestowed him with great powers and the means to achieve everything.

First Alexander traveled west until he saw the sun setting in a pool of black mud. There, on Allah’s command, he punished the wicked inhabitants and rewarded the righteous. Next he traveled east until he found peoples who were constantly exposed to the flaming rays of the sun. They recieved the same treatment by Alexander’s hands.

Finally Alexander traveled to the land of the Two Mountains. The backward peoples of this region were harrassed by Gog and Magog: the forces of chaos and destruction. Between the Two Mountains Alexander built a wall of iron blocks, joining the blocks with molten copper or brass. Gog and Magog were not able to scale the wall nor could they destroy it.

The sura ends with the statement that Alexander’s wall, which protects mankind against its foes, will continue to exist until the Day of Resurrection, when Allah will level it to dust.

(Though the identification of Dhul-Qarnain with Alexander the Great is supported by most mainstream Muslim scholars, other scholars might support very different viewpoints. It is also said Dhul-Qarnain actually refers to the Persian King Cyrus the Great, or to the legendary Babylonian King Gilgamesh.)

The Salt Range derives its name from extensive deposits of rock salt. The Range stands as remnant of forts with bastions and temples. Exceptionally, this region maintains an almost continuous record of history that can define the evolution of society. Forts and temples surviving along the range are a reminder of how untouched many of the ancient remnants are. Alexander from Macedon came to this Range twice; one from Taxila and later when his forces refused to go any further from the banks of the River Beas. From here he marched towards the Arabian Sea on his way to Babylon.

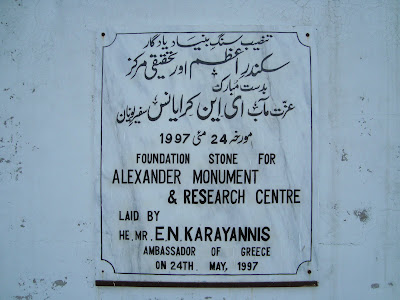

And, now an NGO is constructing a monument of Alexander near Jalalpur town in the foot of the Salt Range in district Jhelum.

|

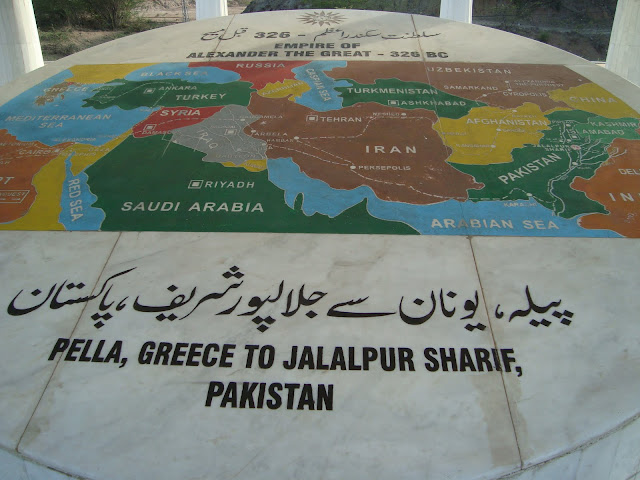

| Map showing Alexander’s March from Pella, Greece, to Jalalpur Sharif Pakistan – 326 BC |

For those who take their first chance to the area, the landscape all along the Salt Range is rock-strewn, lacking in softness and loveliness. In many parts, it becomes barren and uninviting. But, in truth the range is dotted with historical wonders, romantic legends, archaeological remains, and varying geological formations. Surroundings are very quiet. Urial is also found in the Range though facing extinction. A journey along the range is exiting as well as informative.

After crossing the River Jhelum from Rasul Barrage, one passes through Rasul Barrage Wildlife Sanctuary. Environs are green and the wetland is full of lotus. Flocks of Siberians Cranes and Strokes and local black winged Stilts are the common sights in the area. Though at the dawn of a hot June day, I was able to see only few Tobas perching over their morning catch and a few flocks of Murghabis (wild ducks).

Turn west along the Range from

Mishri Mor bus stop in the beautiful ‘bela’ of the River Jhelum and the road will take you to the town of Jalalpur. One could come on this road from

Jhelum side but these days the Jhelum-Pind Dadan Khan Road is closed due to want of bridges on the torrents coming down the range to join River Jhelum so you can only come through Rasul Barrage. The River Jhelum used to flow full to the capacity but now it remains mostly dry. Water of the River Jhelum is transferred from Rasul Barrage to the River Chenab for strategic water management in the country.

Jalalpur Sharif, as the town is called, is opposite village

Mong where the conflict between Alexander and Porus took place. Mong used to be the garrison of King Porus who had assembled 30,000 men, 2000 cavalry, and 200 elephant to fight against the Macedonians.

Right on the Jhelum-Pind Dadan Khan Road, tucked inside the Salt Range, is ancient Jalalpur that was built by Alexander in the memory of his general who was killed in the battle with Porus. Coins found among the ruins date back to the period of Graeco-Bactrian kings. Remains of the ancient walls are still there at the summit of the hill, which rise 1000 feet above the present-day Jalalpur.

It is at Jalalpur that in the absence of any route marking or sign posting, we started asking for the monument that is being made in the memory of Alexander. An old driver came up to help and gave us some directions to go onto a road leading to village Wagh inside the range where we were to find the unfinished monument structure.

The structure of the monument stands on the bank of a torrent, which flows during rainy seasons. The towering pedestal is very graceful and on the platform stands a room. On the roof of the wide room, and flanked by Grecian style arches, is painted a map of Alexander’s empire from Greece to South Asia showing the route (Hund – Taxila – Jalalpur – Beas – back to Jalalpur and to the Arabian sea along River Jhelum) he followed in this part of the world.

There is no doubt that this scenic place could be turned into a lucrative and busy tourist attraction and may be a research facility. Presently, not much is going on and thorny bushes are placed on the stairs to stop any one going up on the roof to see the map. The colors of the map are already peeling. The pits all around the monument suggest that some trees were also planted but only a couple of them have survived. Names of the donors have been written in different colors (along with the legend for the color code) on the wall facing road. There was no one, not even a janitor, who could tell us about the current state of affairs or why the construction work has been stopped. Why? Lack of funds, lack of interest, or both!?

Alexander was undoubtedly a man of great substance: “He was an illustrious soldier who always followed the rules of war. He brought disciplines of medicine (Tibb-e-Yunani) and philosophy to what is now Pakistan. More than two thousand years ago he recognized the enormous potential in terms of commerce and trade of the immediate hinterland of Karachi. He called this place the bridge between east and west,” reads a report of Wildlife and Environment Quarterly. Not always. Travel writer and researcher

Salman Rashid says Alexander did not only get away with murdering 7,000 soldiers from the central subcontinent who had joined the Pakhtoons in an attempt to defend the Masaga Fort, he also gives him a lenient title of a daghabaaz (at its most mundane a fraud, at worst a cheat). And, “we all by now know that it takes a general more than this to conquer the world,” adds Ashaar Rahman.

People with time and will to explore are constantly looking for quiet and new destinations. Locally, if nothing else, this monument could give a boost to

rural tourism and economy.

Tags: Travel. Places, Greece, Alexander, Jalalpur Sharif, Pella, Pakistan, King Porus, Jhelum,

Click to Expand & Play

Click to Expand & Play

2:14 PM

2:14 PM  Jalal Hameed

Jalal Hameed