Our Announcements

Sorry, but you are looking for something that isn't here.

Posted by admin in Islam: The Universal Message of Peace, Women In Islam on October 20th, 2013

Rabi’ah al-Adawiyya, a major spiritual influence in the classical Islamic world, is one of the central figures of the spiritual tradition. She was born around the year 717 C.E. in what is now Iraq.

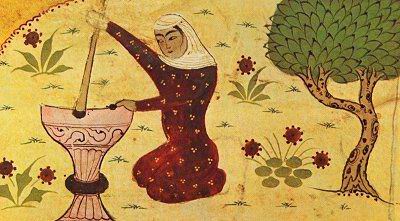

GrindingGrain~10th_16thCenturyPersianDictionary~grind_large

Rabia al Basri

717-801

Not much is known about Rabia al Basri, except that she lived in Basra in Iraq, in the second half of the 8th century AD. She was born into poverty. But many spiritual stories are associated with her and what we can glean about her is reality merged with legend. These traditions come from Farid ud din Attar a later sufi saint and poet, who used earlier sources. Rabia herself though has not left any written works.

HAZRAT RABIA BASRI (rahmatullahi alyha)

Hazrat Rabia’s (rahmatullahi alayha) parents were so poor that there was no oil in the house to light a lamp, nor a cloth even to wrap her with.

She was the -fourth child in the family. Her mother requested her husband to borrow some oil from a neighbour, but he had resolved in his life never to ask for anything from anyone except the Creator; so he pretended to go to the neighbour’s door and so gently knocked at it that he might not be heard and answered, and therefore returned home empty-handed. He told his wife that the neighbour did not open the door, so he came disappointed.

In the night the Prophet appeared to him in a dream and told him, “Your newly born daughter is a favourite of the Lord, and shall lead many Muslims to the Path of Deliverance. You should approach the Amir of Basra and present him with a letter in which should be written this message, “You offer Darud to the Holy Prophet (Sallallaahu Alayhi Wa Sallam) one hundred times every night and four hundred times every Thursday night. However, since you failed to observe the rule last Thursday, as a penalty you must pay the bearer four hundred dinars. Hazrat Rabia’s (rahmatullahi alayha) father got up and went straight to the Amir, with tears of joy rolling down his cheeks. The Amir was delighted on receiving the message and knowing that he was in the eyes of the Prophet (Sallallaahu Alayhi Wa Sallam) he distributed in gratitude one thousand dinars to the poor and paid with joy four hundred to Rabia’s father and requested him to come to him whenever he required anything as he will benefit very much by the visit of such a soul dear to the Lord.”

After her father’s death, there was a famine in Basra, and during that she was parted from her family. It is not clear how she was traveling in a caravan that was set upon by robbers. She was taken by the robbers and sold into slavery.

Her master worked her very hard, but at night after finishing her chores Rabia would turn to meditation and prayers and praising the Lord. Foregoing rest and sleep she spent her nights in prayers and she often fasted during the day.

There is a story that once, while in the market, she was pursued by a vagabond and in running to save herself she fell and broke her arm. She prayed to the Lord .

“I am a poor orphan and a slave, Now my hand too is broken. But I do not mind these things if Thou be pleased with me. “

and felt a voice reply:

“Never mind all these sufferings. On the Day of Judgement you shall be accorded a status that shall be the envy of the angels even”

One day the master of the house spied her at her devotions. There was a divine light enveloping her as she prayed. Shocked that he kept such a pious soul as a slave, he set her free. Rabia went into the desert to pray and became an ascetic. Unlike many sufi saints she did not learn from a teacher or master but turned to God himself.

Throughout her life, her Love of God. Poverty and self-denial were unwavering and her constant companions. She did not possess much other than a broken jug, a rush mat and a brick, which she used as a pillow. She spent all night in prayer and contemplation chiding herself if she slept for it took her away from her active Love of God.

As her fame grew she had many disciples. She also had discussions with many of the renowned religious people of her time. Though she had many offers of marriage, and tradition has it one even from the Amir of Basra, she refused them as she had no time in her life for anything other than God.

More interesting than her absolute asceticism, however, is the actual concept of Divine Love that Rabia introduced. She was the first to introduce the idea that God should be loved for God’s own sake, not out of fear–as earlier Sufis had done.

She taught that repentance was a gift from God because no one could repent unless God had already accepted him and given him this gift of repentance. She taught that sinners must fear the punishment they deserved for their sins, but she also offered such sinners far more hope of Paradise than most other ascetics did. For herself, she held to a higher ideal, worshipping God neither from fear of Hell nor from hope of Paradise, for she saw such self-interest as unworthy of God’s servants; emotions like fear and hope were like veils — i.e. hindrances to the vision of God Himself.

She prayed:

“O Allah! If I worship You for fear of Hell, burn me in Hell,

and if I worship You in hope of Paradise, exclude me from Paradise.

But if I worship You for Your Own sake,

grudge me not Your everlasting Beauty.”

Rabia was in her early to mid eighties when she died, having followed the mystic Way to the end. By then, she was continually united with her Beloved. As she told her Sufi friends, “My Beloved is always with me”

line

Brief Notes:

Rabi’a al-‘Adawiyya

an 8th Century Islamic Saint from Iraq

By Kathleen Jenks, Ph.D.

______________________________________________________[Citations and data are from Margaret Smith, The Way of the Mystics: The Early Christian Mystics and the Rise of the Sufis, NY: Oxford University Press, 1978. See the Islamic Bookstore for sample pages. I strongly recommend her book].

One of the most famous Islamic mystics was a woman: Rabi’a al-‘Adawiyya (c.717-801). This 8th century saint was an early Sufi who had a profound influence on later Sufis, who in turn deeply influenced the European mystical love and troubadour traditions. Rabi’a was a woman of Basra, a seaport in southern Iraq. She was born around 717 and died in 801 (185-186). Her biographer, the great medieval poet Attar, tells us that she was “on fire with love and longing” and that men accepted her “as a second spotless Mary” (186). She was, he continues, “an unquestioned authority to her contemporaries” (218).

As Cambridge professor Margaret Smith explains, Rabi’a began her ascetic life in a small desert cell near Basra, where she lost herself in prayer and went straight to God for teaching. As far as is known, she never studied under any master or spiritual director. She was one of the first of the Sufis to teach that Love alone was the guide on the mystic path (222). A later Sufi taught that there were two classes of “true believers”: one class sought a master as an intermediary between them and God — unless they could see the footsteps of the Prophet on the path before them, they would not accept the path as valid. The second class “…did not look before them for the footprint of any of God’s creatures, for they had removed all thought of what He had created from their hearts, and concerned themselves solely with God. (218)

Rabi’a was of this second kind. She felt no reverence even for the House of God in Mecca: “It is the Lord of the house Whom I need; what have I to do with the house?” (219) One lovely spring morning a friend asked her to come outside to see the works of God. She replied, “Come you inside that you may behold their Maker. Contemplation of the Maker has turned me aside from what He has made” (219). During an illness, a friend asked this woman if she desired anything.

“…[H]ow can you ask me such a question as ‘What do I desire?’ I swear by the glory of God that for twelve years I have desired fresh dates, and you know that in Basra dates are plentiful, and I have not yet tasted them. I am a servant (of God), and what has a servant to do with desire?” (162)

When a male friend once suggested she should pray for relief from a debilitating illness, she said,

“O Sufyan, do you not know Who it is that wills this suffering for me? Is it not God Who wills it? When you know this, why do you bid me ask for what is contrary to His will? It is not well to oppose one’s Beloved.” (221)

She was an ascetic. It was her custom to pray all night, sleep briefly just before dawn, and then rise again just as dawn “tinged the sky with gold” (187). She lived in celibacy and poverty, having renounced the world. A friend visited her in old age and found that all she owned were a reed mat, screen, a pottery jug, and a bed of felt which doubled as her prayer-rug (186), for where she prayed all night, she also slept briefly in the pre-dawn chill. Once her friends offered to get her a servant; she replied,

“I should be ashamed to ask for the things of this world from Him to Whom the world belongs, and how should I ask for them from those to whom it does not belong?” (186-7)

A wealthy merchant once wanted to give her a purse of gold. She refused it, saying that God, who sustains even those who dishonor Him, would surely sustain her, “whose soul is overflowing with love” for Him. And she added an ethical concern as well:

“…How should I take the wealth of someone of whom I do not know whether he acquired it lawfully or not?” (187)

She taught that repentance was a gift from God because no one could repent unless God had already accepted him and given him this gift of repentance. She taught that sinners must fear the punishment they deserved for their sins, but she also offered such sinners far more hope of Paradise than most other ascetics did. For herself, she held to a higher ideal, worshipping God neither from fear of Hell nor from hope of Paradise, for she saw such self-interest as unworthy of God’s servants; emotions like fear and hope were like veils — i.e., hindrances to the vision of God Himself. The story is told that once a number of Sufis saw her hurrying on her way with water in one hand and a burning torch in the other. When they asked her to explain, she said:

“I am going to light a fire in Paradise and to pour water on to Hell, so that both veils may vanish altogether from before the pilgrims and their purpose may be sure…” (187-188)

She was once asked where she came from. “From that other world,” she said. “And where are you going?” she was asked. “To that other world,” she replied (219). She taught that the spirit originated with God in “that other world” and had to return to Him in the end. Yet if the soul were sufficiently purified, even on earth, it could look upon God unveiled in all His glory and unite with him in love. In this quest, logic and reason were powerless. Instead, she speaks of the “eye” of her heart which alone could apprehend Him and His mysteries (220).

Above all, she was a lover, a bhakti, like one of Krishna’s Goptis in the Hindu tradition. Her hours of prayer were not so much devoted to intercession as to communion with her Beloved. Through this communion, she could discover His will for her. Many of her prayers have come down to us:

“I have made Thee the Companion of my heart,

But my body is available for those who seek its company,

And my body is friendly towards its guests,

But the Beloved of my heart is the Guest of my soul.” [224]

Another:

“O my Joy and my Desire, my Life and my Friend. If Thou art satisfied with me, then, O Desire of my heart, my happiness is attained.” (222)

At night, as Smith, writes, “alone upon her roof under the eastern sky, she used to pray”:

“O my Lord, the stars are shining and the eyes of men are closed, and kings have shut their doors, and every lover is alone with his beloved, and here I am alone with Thee.” (222)

She was asked once if she hated Satan.

“My love to God has so possessed me that no place remains for loving or hating any save Him.” (222)

To such lovers, she taught, God unveiled himself in all his beauty and re-vealed the Beatific Vision (223). For this vision, she willingly gave up all lesser joys.

“O my Lord,” she prayed, “if I worship Thee from fear of Hell, burn me in Hell, and if I worship Thee in hope of Paradise, exclude me thence, but if I worship Thee for Thine own sake, then withhold not from me Thine Eternal Beauty.” (224)

Rabi’a was in her early to mid eighties when she died, having followed the mystic Way to the end. By then, she was continually united with her Beloved. As she told her Sufi friends, “My Beloved is always with me” (224).

line

~~~~~~~~~~

Links to Rabi´a al-Adawiyya

Also see my ~~ISLAM page for general links to Sufism and Women in Islam

[FYI: some of those links also include Rabi’a]

~~~~~~~~~~

~http://www.ilstu.edu/~mtavakol/lhudson.html

[Added 1 December 2001]: This is “Islamic Mysticism and Gender Identity,” an excellent, lengthy, footnoted paper by Leonard E. Hudson. The author begins with a famous and beautiful passage from the earliest Sufi woman-saint, Rabi’a, and then comments:

…The Sufis pursue the love of God in the same manner that one person, enflamed with the fires of passion, pursues another. It is therefore of no great surprise that Sufi literature often takes the form of love poems. What is surprising, however, is the fact that–despite the mysogynistic tradition of orthodox Islam, and the typical attitude of Muslim theologians that women possess, “little capacity for thought, and less for religion” –many of the greatest Islamic mystics have been women….

After a brief discussion of Sufi tenets (including a lack of gender distinctions since gender is burned away in the love of God), the author turns to the life of Rabi’a:

…Little is known of her early years, save that she was born sometime between 712-717 to a poor family in the city of Basra (located in what is now Iraq), spent her youth as a slave, and was later freed. What we do know of her, however, is that throughout her life, her asceticism was absolute and unwavering, as was her Love of God. Poverty and self-denial were Rabi’a’s constant companions. For example, her typical possessions are said to have been a broken jug from which she drank, an old rush mat to sit upon, and a brick for a pillow. She spent each night in prayer and often chided herself for sleeping, as it prevented her constant contemplation and active Love of God. She rebuked all offers of marriage–of which there were many –because she had no room for anything in her life that might distract her from complete devotion to God. Indeed, in this same manner she “rebuffed anything that could distract her” from the Beloved, i.e., God. More interesting than her absolute asceticism, however, is the actual concept of Divine Love that Rabi’a introduced. She was the first to introduce the idea that God should be loved for God’s own sake, not out of fear–as earlier Sufis had done. For example, she is reported to have walked the streets of Basra, a flaming torch in one hand, and a bucket of water in the other. When her intentions were questioned, Rabi’a replied: I want to pour water into Hell and set fire to Paradise so that these two veils disappear and nobody worships God out of fear of Hell or hope for Paradise, but only for the sake of His eternal beauty….

Moving beyond Rabi’a’s life, the author considers such difficult issues as the gender-transcendent ideal of Sufism, today’s Islamic feminists and their criticism of Sufis, and “homosocial” relationships (which touch upon Rumi’s life). I found it a literate, well-researched paper.

http://www.digiserve.com/mystic/Muslim/Rabia/index.html

[Added 1 December 2001]: From D. Platt comes “About Rabi´a al-Adawiyya,” a brief essay on Rabi’s’ life. (Note: if you click on “Select A New Mystic” from the site’s lefthand menu, you’ll find a good choice of other Islamic mystics and scholars.)

Also included is a section explaining how Charles Upton, author of Doorkeeper of the Heart: Versions of Rabi´a, worked with English translations of traditional sayings from Rabi’a. From the menu on the left, you can select from some of these sayings — they read beautifully, but for a non-Islamicist to re-work these passages, based only on English translations (literal or otherwise), and following his own muse, makes me nervous. Still, the underlying fervour feels accurate enough. [Note: for more of Upton’s excerpts, see: http://www.sufism.org/books/rabiaex.html; and for a page on the slim, 56 page book itself, see: http://www.sufism.org/books/rabia.html.]

http://sufimaster.org/adawiyya.htm

[Added 1 December 2001]:This is a lengthy, devotional page filled with sayings and legendary tales about Rabi’a. Are such legends “true”? Well, yes and no. In a sense, it doesn’t matter since these are “teaching stories.” Regardless, they are often lovely and evocative — and interspersed among them I found some especially interesting pieces. For example, here’s a sad one — but please don’t use this as an excuse to condemn Islam — unfortunately, nearly identical sentiments have been expressed by Christian males about saintly Christian females. In other words, this is a patriarchal bias, not a spiritual one:

…She is often referred to as the first true Saint (waliya) of Islam and was praised, not because she in any way represented womankind, but because as someone said, “When a woman walks in the Way of Allah like a man she cannot be called a woman”….

This one has the earthy practicality, humor, and compassion of a Teresa of Avila:

…Another story tells of how one day Hasan al-Basri saw Rabi`a near a lake. Throwing his prayer rug on top of the water, he said, “Rabi`a come! Let us pray two ruk`u here.” She replied, “Hasan, when you are showing off your spiritual goods in the worldly market, it should be things which your fellow men cannot display.” Then she threw her prayer rug into the air and flew up onto it. “Come up here, Hasan, where people can see us,” she cried. But seeing his sadness Rabi`a sought to console him, so she said, “Hasan, what you did fishes can do, and what I did flies can do. But the real business is outside these tricks. One must apply oneself to the real business”….

And this one relates to the Mecca story to which I refer below:

…There is a story that Rabi`a was once on her way to Mecca. When she was half-way there she saw the Ka`ba coming to meet her and she said, “It is the Lord of the House Whom I need. What have I to do with the House? I need to meet with Him Who said: ‘Whoso approaches Me by a span’s length I will approach him by the length of a cubit.’ The Ka`ba which I see has no power over me. What does the Ka`ba bring to me?” ….

http://www.islamicresources.com/Prominent_Muslims/Others/

rabiah_basri_mystic.htm

[Added 1 December 2001]:This is a brief, no frills page on the life and sayings of Rabi’a. You will have read much of this elsewhere in other links on my site but some of the sayings are new — and worthwhile.

http://www.maryams.net/text/biog.html

[Link updated 16 January 20o3]

[Added 1 December 2001]:From Maryams.net come biographical sketches of Muslim women — this one’s on Rabi’a, brief but useful and with good resources (print and web) listed at the end. Here is how it opens:

Little is known for sure about Rabi`a al-‘Adawiyya al-Qaysiyya (known as Rabi`a of Basra), revered as one of the earliest and greatest Sufi mystic ascetics in Islam.

She was born into poverty: the fourth girl (hence her name Rabi`a meaning “fourth”) around 95-99 A.H. in Basra. It is thought she was captured after being orphaned and sold into slavery, becoming a flautist.

Rabi`a was freed by her owner after an event in which he was startled by observing an enveloping radiance (sakina) around her whilst she was rapt in prayer. It is said that she retreated into the desert and began occupying herself with a life of worship….

If you’re interested in contemporary Muslim women’s issues, or in other Muslim women mystics and leaders (including contemporary author and activist, Margret Marcus, the first American Jewish woman to convert to Islam), this is a great place for browsing. Most of the entries are relatively brief, so they won’t demand too much of a busy schedule.

~http://www.clearlight.com/~sufi/fiam1.htm

[Added 1 December 2001]: This is another brief publisher’s page promoting First among Sufis: The Life & Thought of Rabia al-Adawiyya by Widad El Sakkakini. I haven’t read it so you’ll have to judge for yourself if it’s worth your time.

http://www.siddhayoga.org/community/families/tales_2000/rabia/

[Added 28 November 2001]: This is The Golden Tales: The Life of Rabi’a, a children’s book (also available as a video). From the video description, at least one obvious liberty has been taken with history: Rabi’a is said to have lived her ascetic life in Mecca, not Basra, which is a significant error, especially since we know her thoughts on Mecca — it was, she said, the Lord of the house who interested her, not his house. She certainly never spent her life in Mecca. The book and/or video might, however, be evocative and engaging enough to appeal to children who really wouldn’t care where she lived.

line

Rabia was a mystic, or a holy woman, who spent her whole life in devotion to God. She was born over a thousand years ago, in the city of Basra, in Iraq. Long ago, in the city of Basra, there lived a young woman named Rabia. She came from a poor family. She and her three sisters suffered greatly, for their parents had died and then there was a great famine.

It was a violent and dangerous time. The famine made people cruel, ready to do almost anything to survive. Rabia knew it was not safe to walk alone in the town, but she had to find food. One evening, she slipped out of the house, and into the street. Suddenly, someone caught her, holding her roughly. A hand was over her mouth — she could not cry for help. She had been captured by a wicked dealer in slaves, who then sold her in the market, for just a few coins.

As a slave, Rabia served in the house of a rich man. She had to work hard, for long hours. Yet all the time, through out the day as she worked, she prayed and fasted. Even at night, she slept little. She often stood praying as dawn broke and her daily tasks began.

One hot night, Rabia’s master found he could not sleep. He got up, and walked over to the window of his room. He looked down, into the courtyard below. There, he saw the solitary figure of Rabia, his slave. Her lips moved in prayer, and he could just catch the words in the still night air. Oh God, Thou knowest that the desire of my heart is to obey Thee, and if the affair lay with me, I would not rest one hour from serving Thee, but Thou Thyself has set me under the hand of Thy creature. For this reason I come late to Thy service. . .

There was something very strange about the scene. At first, the master could not quite understand what it was. Then he realized. There was a lamp above Rabia’s head. Ithung there, quite still — but without a chain. As he watched, its light filled the whole house. Suddenly, he was afraid. He returned to his bed, and layawake, thinking of what he had seen. He was certain of only one thing. Such a woman should not be a slave. In the morning, he called Rabia to him, and spoke to her kindly. He told her he would set her free.

“I beg your permission to depart,” murmured Rabia, and her master agreed at once. Rabia set off out of the town, deep into the desert. There she lived as a hermit, alone for awhile, serving God. Later, she went to Makkah as a pilgrim.

line

The Sayings of Rabia

By Richard Monckton Milnes, Lord Houghton (1809-1885)

I

A PIOUS friend one day of Rabia asked,

How she had learnt the truth of Allah wholly?

By what instructions was her memory tasked-

How was her heart estranged from this world’s folly?

She answered-‘Thou, who knowest God in parts, 5

Thy spirit’s moods and processes can tell; I only know that in my heart of hearts

I have despised myself and loved Him well.’

II

Some evil upon Rabia fell,

And one who loved and knew her well 10

Murmured that God with pain undue

Should strike a child so fond and true:

But she replied- ‘Believe and trust

That all I suffer is most just;

I had in contemplation striven 15

To realize the joys of heaven;

I had extended fancy’s flights

Through all that region of delights,-

Had counted, till the numbers failed,

The pleasures on the blest entailed,- 20

Had sounded the ecstatic rest

I should enjoy on Allah’s breast;

And for those thoughts I now atone

That were of something of my own,

And were not thoughts of Him alone.’ 25

III

When Rabia unto Mekkeh came,

She stood awhile apart-alone,

Nor joined the crowd with hearts on flame

Collected round the sacred stone.

She, like the rest, with toil had crossed 30

The waves of water, rock, and sand,

And now, as one long tempest-tossed,

Beheld the Kaabeh’s promised land.

Yet in her eyes no transport glistened;

She seemed with shame and sorrow bowed; 35

The shouts of prayer she hardly listened,

But beat her heart and cried aloud:-

‘O heart! weak follower of the weak,

That thou should’st traverse land and sea,

In this far place that God to seek 40

Who long ago had come to thee!’

IV

Round holy Rabia’s suffering bed

The wise men gathered, gazing gravely- ‘Daughter of God!’ the youngest said,

‘Endure thy Father’s chastening bravely; 45

They who have steeped their souls in prayer Can every anguish calmly bear.’

She answered not, and turned aside,

Though not reproachfully nor sadly;

‘Daughter of God!’ the eldest cried, 50

‘Sustain thy Father’s chastening gladly; They who have learnt to pray aright,

From pain’s dark well draw up delight.’

Then she spoke out- ‘Your words are fair;

But, oh! the truth lies deeper still; 55

I know not, when absorbed in prayer,

Pleasure or pain, or good or ill;

They who God’s face can understand

Feel not the motions of His hand.’

Courtesy: http://www.rabianarker.com/html/rabia_stories.html

For More Information Visit

http://www.rabianarker.com/html/rabia_stories.html

I carry a torch in one hand

And a bucket of water in the other:

With these things I am going to set fire to Heaven

And put out the flames of Hell

So that voyagers to God can rip the veils

And see the real goal.

***************

Brothers, my peace is in my aloneness.

My Beloved is alone with me there, always.

I have found nothing in all the worlds

That could match His love,

This love that harrows the sands of my desert.

If I come to die of desire

And my Beloved is still not satisfied,

I would live in eternal despair.

To abandon all that He has fashioned

And hold in the palm of my hand

Certain proof that He loves me—

That is the name and the goal of my search.

Rabi´a al-Adawiyya, translation by Andrew Harvey and Eryk Hanut – ‘Perfume of the Desert’

~~

O Lord,

If tomorrow on Judgment Day

You send me to Hell,

I will tell such a secret

That Hell will race from me

Until it is a thousand years away.

O Lord,

Whatever share of this world

You could give to me,

Give it to Your enemies;

Whatever share of the next world

You want to give to me,

Give it to Your friends.

You are enough for me.

O Lord,

If I worship You

From fear of Hell, burn me in Hell.

O Lord,

If I worship You

From hope of Paradise, bar me from its gates.

But if I worship You for Yourself alone

Then grace me forever the splendor of Your Face.

Rabi´a al-Adawiyya, translation by Andrew Harvey and Eryk Hanut – ‘Perfume of the Desert’

~~

In love, nothing exists between heart and heart.

Speech is born out of longing,

True description from the real taste.

The one who tastes, knows;

the one who explains, lies.

How can you describe the true form of Something

In whose presence you are blotted out?

And in whose being you still exist?

And who lives as a sign for your journey?

Rabia al-Adawiyya

~~

I have two ways of loving You:

A selfish one

And another way that is worthy of You.

In my selfish love, I remember You and You alone.

In that other love, You lift the veil

And let me feast my eyes on Your Living Face.

Rabi´a al-Adawiyya. Doorkeeper of the heart:versions of Rabia. Trans. Charles Upton

~~

The source of my suffering and loneliness is deep in my heart.

This is a disease no doctor can cure.

Only Union with the Friend can cure it.

Rabi´a al-Adawiyya, translation by Andrew Harvey and Eryk Hanut – ‘Perfume of the Desert’

~~